The biblical story of Palm Sunday is recorded in all four of the Gospels (Matthew 21:1-11; Mark 11:1-10; Luke 19:28-38; and John 12:12-18). Five days before the Passover, Jesus came from Bethany to Jerusalem. Having sent two of His disciples to bring Him a colt of a donkey, Jesus sat upon it and entered the city.

People had gathered in Jerusalem for the Passover, the most sacred week of the Jewish Year and were looking for Jesus, both because of His great works and teaching and because they had heard of the miracle of the resurrection of Lazarus. When they heard that Christ was entering the city, they went out to meet Him with palm branches, laying their garments on the ground before Him, and shouting, “Hosanna! Blessed is he that comes in the Name of the Lord, the King of Israel!”

From the east, Jesus rode a donkey down the Mount of Olives, cheered by his followers. He rides the colt to the city surrounded by a crowd of enthusiastic followers and sympathizers, who spread their cloaks, strew leafy branches on the road, and shout, “Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Blessed is the coming kingdom of our ancestor David! Hosanna in the highest heaven!”

Jesus was from the peasant village of Nazareth, his message was about the kingdom of God, and his followers came from the peasant class. They had journeyed to Jerusalem from Galilee, about a hundred miles to the north, a journey that is the central section and the central dynamic of Mark’s gospel. Mark’s story of Jesus and the kingdom of God has been aiming for Jerusalem, pointing toward Jerusalem. It has now arrived. On the opposite side of the city, from the west, Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Idumea, Judea, and Samaria, entered Jerusalem at the head of a column of imperial cavalry and soldiers

At the outset of His public ministry Jesus proclaimed the kingdom of God and announced that the powers of the age to come were already active in the present age (Luke 7:18-22, Mark 1:14-15). His words and mighty works were performed “to produce repentance as the response to His call, a call to an inward change of mind and heart which would result in concrete changes in one’s life, a call to follow Him and accept His messianic destiny. The triumphant entry of Jesus into Jerusalem is a messianic event, through which His divine authority was declared.

Mark concludes his advance summary of Jesus’s message with, “Repent, and believe in the good news” (1:15).

The word “repent” has two meanings here, both quite different from the later Christian meaning of contrition for sin. From the Hebrew Bible, it has the meaning of “to return,” especially “to return from exile,” an image also associated with “way,” “path,” and “journey.” To believe in the good news,” as Mark puts it, means to trust in the news that the kingdom of God is near and to commit to that kingdom. And to whom did Jesus direct his message about the kingdom of God and the “way”? Primarily peasants

In Mark (and the other gospels), Jesus never goes to a city (except Jerusalem, of course). Though the first half of Mark is set in Galilee, Mark does not report that Jesus went to its largest cities, Sepphoris and Tiberias, even though the first is only four miles from Nazareth and the second is on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, the area of most of Jesus’s activity. Instead, Jesus speaks in the countryside and in small towns like Capernaum. Why? The most compelling answer is that Jesus saw his message as to and for peasants

Jerusalem becomes central in the section of Mark that tells the story of Jesus’s journey from Galilee to Jerusalem. It begins roughly halfway through Mark with Peter’s affirmation that Jesus is the Messiah. The next two and a half chapters, leading to Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, are about what it means to follow Jesus, to be a genuine disciple. Mark develops this theme by weaving together several subthemes:

• Following Jesus means following him on the way.

• The way leads to Jerusalem.

• Jerusalem is the place of confrontation with the authorities.

Jerusalem is the. place of death and resurrection

Commonly called the “first prediction of the passion,” it is followed by two more solemn announcements anticipating Jesus’s execution that structure this part.

Each of these anticipations of Jesus’s execution is followed by teaching about what it means to follow Jesus.

3 meanings of Palm Sunday

1. Palm Sunday summons us to behold our king: the Word of God made flesh. We are called to behold Him not simply as the One who came to us once riding on a colt, but as the One who is always present in His Church, coming ceaselessly to us in power and glory at every Eucharist, in every prayer and sacrament, and in every act of love, kindness and mercy. He comes to free us from all our fears and insecurities, “to take solemn possession of our soul, and to be enthroned in our heart,” as someone has said. He comes not only to deliver us from our deaths by His death and Resurrection, but also to make us capable of attaining the most perfect fellowship or union with Him. He is the King, who liberates us from the darkness of sin and the bondage of death. Palm Sunday summons us to behold our King: the vanquisher of death and the giver of life.

In the gospels, the movements of both John the Baptist and Jesus had an anti-temple dimension. John’s baptism was for the “forgiveness of sins.” But forgiveness was a function that temple theology claimed for itself, mediated by sacrifice in the temple. Like John, Jesus pronounced forgiveness apart from temple sacrifice. It is implicit in much of his activity, including his eating with “tax collectors and sinners,” who were seen as intrinsically impure, but it becomes explicit as well

Thus in these voices from the time of Jesus, Jerusalem with its temple was still seen as “the city of God” that called forth Jewish devotion. But it was also the center of a local domination system, the center of the ruling class, the center of great wealth, and the center of collaboration with Rome.

2. Palm Sunday summons us to accept both the rule and the kingdom of God as the goal and content of our Christian life.

In Mark, Jesus’s message is not about himself-—not about his identity as the Messiah, the Son of God, the Lamb of God, the Light of the World, or any of the other exalted terms familiar to Christians. Of course, Mark affirms that Jesus is both the Messiah and the Son of God; he tells us so in the opening verse of the gospel: “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.”

But this is not part of Jesus’s own message. He neither proclaims nor teaches this, nor does this form part of his followers’ teaching during his lifetime. Rather, in Mark only voices from the Spirit world speak of Jesus’s special identity. It is about the kingdom

In the first century, “kingdom” was a political term. Jesus’s hearers (and Mark’s community) knew of and lived under kingdoms: the kingdoms of Herod and his sons, the kingdom of Rome. Jesus could have spoken of the family of God, the community of God, or the people of God, but, according to Mark, he spoke of the kingdom of God. To his hearers, it would have suggested a kingdom very different from the kingdoms they knew, very different from the domination systems that ruled their lives. And Jesus’s message in Mark, is about the already present kingdom of God that is also yet to come in its fullness.

We draw our identity from Christ and His kingdom. The kingdom is Christ – His indescribable power, boundless mercy and incomprehensible abundance given freely to man. The kingdom does not lie at some point or place in the distant future. In the words of the Scripture, the kingdom of God is not only at hand (Matthew 3:2; 4:17), it is within us (Luke 17:21). The kingdom is a present reality as well as a future realization (Matthew 6:10). Theophan the Recluse wrote the following words about the inward rule of Christ the King:

“The Kingdom of God is within us when God reigns in us, when the soul in its depths confesses God as its Master, and is obedient to Him in all its powers. Then God acts within it as master ‘both to will and to do of his good pleasure’ (Philippians 2:13).

The kingdom of God is the life of the Holy Trinity in the world. It is the kingdom of holiness, goodness, truth, beauty, love, peace and joy. These qualities are not works of the human spirit. They proceed from the life of God and reveal God. Christ Himself is the kingdom.

3. Palm Sunday summons us to behold our king – the Suffering Servant. We cannot understand Jesus’ kingship apart from the Passion. Filled with infinite love for the Father and the Holy Spirit, and for creation, in His inexpressible humility Jesus accepted the infinite abasement of the Cross. He bore our griefs and carried our sorrows; He was wounded for our transgressions and made Himself an offering for sin (Isaiah 53). His glorification, which was accomplished by the resurrection and the ascension, was achieved through the Cross.

In the fleeting moments of exuberance that marked Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem, the world received its King, the king who was on His way to death. His Passion, however, was no morbid desire for martyrdom. Jesus’ purpose was to accomplish the mission for which the Father sent Him.

21 Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem

Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem during the Feast of Passover is recorded in Luke 19:35-38 and Mark 11:7-10.

His triumphal entry was prophesied in Psalm 118 and Zechariah 9:9. Part of the observance of the Feast of Passover was the reciting of the Hallel (Psalm 118). The words of Psalm 118 were shouted by the people as Jesus entered the gates of Jerusalem seated on a colt, the foal of a donkey, as was prophesied in Zechariah 9:9.

Prophecy – The Coming Messiah

“Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion; shout, O daughter of Jerusalem: behold, thy King cometh unto thee: he is just, and having salvation; lowly, and riding upon an ass, and upon a colt the foal of an ass.”

– Zechariah 9:9

Fulfillment

Mark 11:7-10

7 They brought the colt to Jesus and put their coats on it; and He sat on it. 8 And many spread their coats in the road, and others spread leafy branches which they had cut from the fields. 9 Those who went in front and those who followed were shouting:

“Hosanna! BLESSED IS HE WHO COMES IN THE NAME OF THE LORD;

10 Blessed is the coming kingdom of our father David; Hosanna in the highest!”

Luke 19:35-38

“And they brought him to Jesus: and they cast their garments upon the colt, and they set Jesus thereon. And as he went, they spread their clothes in the way. And when he was come nigh, even now at the descent of the mount of Olives, the whole multitude of the

disciples began to rejoice and praise God with a loud voice for all the mighty works that they had seen; Saying, Blessed be the King that cometh in the name of the Lord: peace in heaven, and glory in the highest.”

Prophecy – The Return of Jesus

The Beautiful Gate, also known as the Golden Gate, is located in the east wall of Jerusalem. It was open at the time of Jesuss triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The gate Jesus went through was destroyed in 70 A.D. The rebuilt gate was sealed by the Muslim conquerors in 1530 A.D. Ezekiel prophesied the closure of this gate around 600 B.C. and that the Prince (Messiah) will enter the gate in the future:

Ezekiel 44:1-3.

“Then he brought me back the way of the gate of the outward sanctuary which looketh toward the east; and it was shut. Then said the LORD unto me; This gate shall be shut, it shall not be opened, and no man shall enter in by it; because the LORD, the God of Israel, hath entered in by it, therefore it shall be shut. It is for the prince; the prince, he shall sit in it to eat bread before the LORD; he shall enter by the way of the porch of that gate, and shall go out by the way of the same.” – Ezekiel 44:1-3.

Recently another gate has been discovered directly beneath the Beautiful Gate. This may be the gate referred to in Scripture.

21a Alternate Triumphal Entry Gate

Jesus may have entered Jerusalem by the Sheep Gate north of the Temple complex. This would be consistent with His role as the Lamb of God, since it was through this gate that the sacrificial lambs were brought into the Temple.

1. Preparation for Christ’s Entry into Jerusalm (1135-1140)

“The frescoes in the parish Church of St. Martin at Nohant-Vicq constitute one of the most extensive and best preserved ensembles of Romanesque monumental painting in central and southwestern France. …a prime example of a major work that has been studied almost exclusively from the standpoint of style. The single painter who executed the frescoes commanded a vigorous and powerful style…the painter’s distinctive manner of generating forms is accompanied by unusual interpretations of narrative subjects…The scene of the Entry [into Jerusalem] is…divided into two parts. The representation of Christ mounted on an ass and greeted by excited youths is contained in the upper register of the south wall. The fortified city of Jerusalem, its gates crowded with youths whose mouths are open in song,is isolated as a separate image…”(Kupfer, 38)”

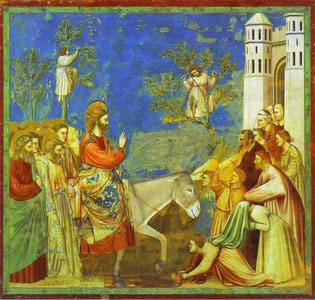

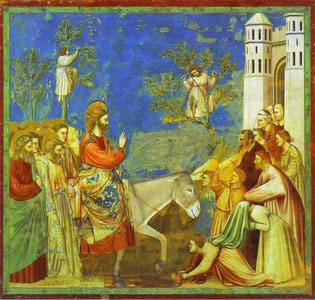

2. Giotto di Bonde, Entry into Jerusalem (1304-06), Fresco, Cappella Scrovegni (Arena Chapel), Padua

Giotto di Bondone (1266/7 – January 8, 1337), better known simply as Giotto, was an Italian painter and architect from Florence in the late Middle Ages. He is generally considered the first in a line of great artists who contributed to the Italian Renaissance.

The late-16th century biographer Giorgio Vasari describes Giotto as making a decisive break with the prevalent Byzantine style and as initiating “the great art of painting as we know it today, introducing the technique of drawing accurately from life, which had been neglected for more than two hundred years.”

3. Duccio di Buoninsegna, detail, Entry into Jerusalem (1308-11)” tempera on wood, Museo dell’Opera

Duccio di Buoninsegna (c. 1255-1260 – c. 1318-1319) was one of the most influential Italian artists of his time. Born in Siena, Tuscany, he worked mostly with pigment and egg tempera and like most of his contemporaries painted religious subjects.

4 Pietro Lorenzetti, Entry of Christ into Jerusalem (c. 1320), Fresco, Lower Church, San Francesco, Assisi

Pietro Lorenzetti (or Pietro Laurati; c. 1280 – 1348) was an Italian painter, active between approximately 1306 and 1345. He was born and died in Siena. He was influenced by Giovanni Pisano and Giotto, and worked alongside Simone Martini at Assisi. He and his brother, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, helped introducenaturalism into Sienese art. In their artistry and experiments with three-dimensional and spatial arrangements, they foreshadowed the art of the Renaissance.Many of his religious works are in churches in Siena, Arezzo, and Assisi.

5 UNKNOWN MASTER, French, Three Scenes (1350-75), Alabaster, Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp

6 Fra Angelico The Entry into Jerusalem, St Mark, Florence

Fra Angelico (c. 1395[1] – February 18, 1455), born Guido di Pietro, was an Early Italian Renaissance painter described by Vasari in his Lives of the Artists as having “a rare and perfect talent”.[2]

7 Pedro Orrente, Entry into Jerusalem (c. 1520), oil on canvas, State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

Pedro Orrente (1580 – 1645) was a Spanish painter of the Baroque period. Born in the village of Murcia. Orrente appears to have studied with el Greco inToledo, where he painted a San Ildefonso before the apparition of St Leocadia and the Birth of Christ for the cathedral. He often moved, painting in Murcia and Cuenca. In Valencia, he painted for the Cathedral. He set up a school, and among his pupils were Esteban March and García Salmerón.

8 Benjamin Robert Haydon, Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem (1814-20), Oil on canvas, 396 x 457 cm, Mount St Mary’s Seminary, Cincinnati

Benjamin Robert Haydon (26 January 1786 – 22 June 1846) was an English historical painterand writer.

9 Albrecht Dürer, Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem (1511), woodcut, The Small Passion Albrecht Dürer (German pronunciation: 21 May 1471 – 6 April 1528)[1] was a German painter, printmaker, engraver, mathematician, and theorist from Nuremberg. His prints established his reputation across Europe when he was still in his twenties, and he has been conventionally regarded as the greatest artist of the Northern Renaissance ever since. His vast body of work includes altarpieces and religious works, numerous portraits and self-portraits, and copper engravings.

• The Foal of Bethpage

• The Procession of the Apostles

• Jesus Beheld the City and Wept over It

• Palm Sunday Procession on the Mount of Olives

• Procession in the Streets of Jerusalem

• Jerusalem, Jerusalem

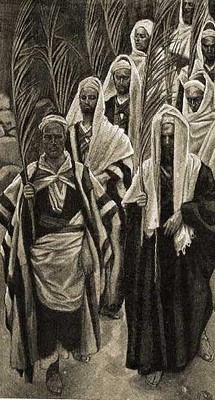

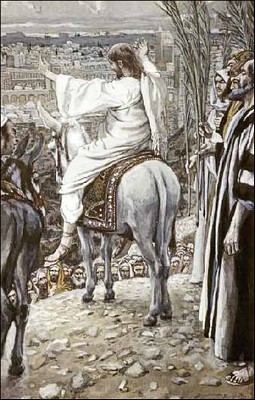

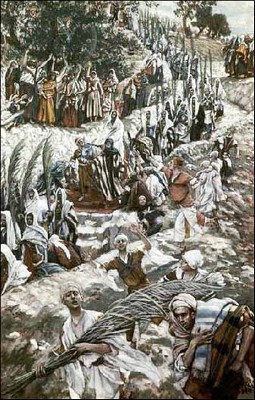

James J. Tissot was a well-known French impressionist painter, who in his later years travelled twice to the Holy Land in order to produced a series of 700 accurate watercolor drawings to illustrate the Old and New Testaments — especially the life of Christ.

11. Wilhelm Morgner Entry Into Jerusalem

Wilhelm Morgner, a German Expressionist painter, trained for the clergy, although he quickly turned to painting as his calling. His close identification with Jesus Christ manifested itself in works that expressed his powerful understanding of the Passion, exemplified here by his color-saturated vision of the Entry into Jerusalem. Sadly, he died a young man, one of millions, on the fields of Flanders during World War I. Still, his discipline to his work left enough paintings to allow reflection upon the creative response to a deep faith and love of Jesus Christ.

12. Photo of Palm Sunday (Cvjetnica) in Croatia, 2007

Rembrandt returned to the subject, "Presentation of Jesus in the Temple" at least 5 times from 1627 to 1654, two paintings, three etchings.

Rembrandt returned to the subject, "Presentation of Jesus in the Temple" at least 5 times from 1627 to 1654, two paintings, three etchings.