2024 Sun March 3

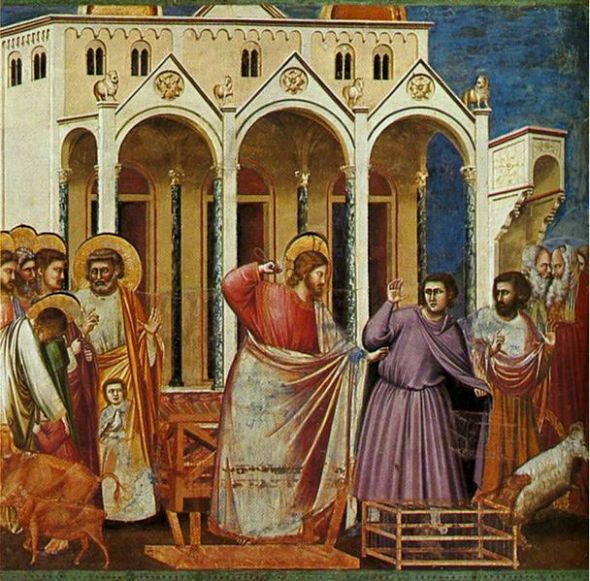

Jesus Cleansing the Temple – Artists’ renditions

Giotto – "Explusion of the Moneychangers from the Temple" (1304-1306)

El Greco– "Purification of the Temple" (1570’s)

Valentine de Boulogne – "Expulsion of the Moneychangers from the Temple " (1620-1625)

The SALT blog for Lent 3, March 3 – “New ways of Encountering God – seeing and believing”

The Salt Blog Takeaways

1. Gospel – Temple will give way to a new means of encountering God

From the Gospel -“In the temple he found people selling cattle, sheep, and doves, and the money changers seated at their tables. Making a whip of cords, he drove all of them out of the temple, both the sheep and the cattle. He also poured out the coins of the money changers and overturned their tables.

From SALT commentary on Lent 3

Lent 3, Year B – March 3, 2024

I.Theme – Old and new covenants

"Moses with the Ten Commandments" – Rembrandt, 1659

The lectionary readings are here or individually:

Old Testament – Exodus 20:1-17

Psalm – Psalm 19 Page 606, BCP

Epistle –1 Corinthians 1:18-25

Gospel – John 2:13-22

Commentary by Rev. Mindi Welton-Mitchell:

We continue to recall the covenants of God with the people, remembering the promises of old. We have remembered the covenants of God with Noah and all of creation, between God and Abraham and Sarah and their family, and now God’s new covenant with the people journeying out of Egypt to be their God in Exodus. God’s covenant requires that the people live in community, and these “ten best ways” (a phrase I borrow from the curriculum Godly Play) are part of that covenant, what the people have to do on their end to uphold the covenant. As we know, the covenant is larger than this, and there are over 600 law codes in Exodus and Leviticus on how the people of Moses’ day were required to live in community with each other, but these ten are the ones that have stood the test of time and have become a part of even our secular society. We remember most of all that to be part of God’s family, we have to be in community with each other.

Psalm 19 is a song of praise about creation and God’s covenant. The writer delights in the law of the Lord–in following God’s law, the psalmist knows he is part of the faithful community, part of God’s family–this is beautiful to the psalmist. The writer desires to be in the company of the faithful to God, and sings the beauty of the laws and ordinances.

John 2:13-22 extends the idea of the faithful community to within and beyond the walls of the Temple. When Jesus enters the temple and sees all sorts of animals being sold for the sacrifices, the temple priests making money off of those coming to exchange for the temple currency, his anger is kindled. In the other three Gospels Jesus turns over the tables, but in John’s Gospel (in which this event happens much earlier, on a first trip to Jerusalem, not the week Jesus is killed as it is in the other Gospels), Jesus makes a whip of cords and drives out the moneychangers and sellers. Jesus desires to end all boundaries to relationship with God. No longer will the poor, who do not have the money for the temple currency or to afford the clean animals for the sacrifice, be turned away, and no longer will those in the temple appear to have special access to God. The temple of God will no longer be in stone, but in Christ, and in our very selves, the body of Christ. No longer will there be arbitrary separation based on human standards, but all who believe will be in relationship with God.

1 Corinthians 1:18-25 is the famous discourse of Paul, that we proclaim Christ crucified. The new covenant in Christ is not written on tablets of stone or seen in a bow in the clouds, but is written in our hearts, as the prophet Jeremiah proclaimed. But more importantly, the new covenant is one in which death is no more. The cross is a stumbling block to those for whom the Messiah was supposed to avoid death. The cross is foolish to those who have had gods defy death. Instead, the cross calls us to put to death the sin within us, and to work to end sin in the world. But death itself is not something to be feared, because death has no power over us. The new covenant is new life–here and to come.

The new covenant, which is emerging in the Lenten passages this season, ends all separation from God. The covenant with Noah and all creation ensures that days and seasons, the passing of years, will never cease. The covenant with Abraham and Sarah promises a family of God that will endure for generations. The covenant with Moses and the people at Sinai ensures a community of faith, the family of God, participation with each other and relationship with God. But Christ calls forth a greater covenant, one in which there are no boundaries that can be drawn on earth or by any power to separate us from God’s love, and that by being the body of Christ, we are the temple for God, that cannot be destroyed because we have the promise of eternal life in Christ.

Visual Lectionary Vanderbilt, Third Sunday in Lent, March 3, 2024

Click here to view in a new window.

Arts and Faith, Lent 3, Year B

By Daniella Zsupan-Jerome, assistant professor of liturgy, catechesis, and evangelization at Loyola University New Orleans.

Quentin Matsys, the Flemish master of the 16th century, was known for his caricature painting and satirical commentary. In his Jesus Chasing the Merchants from the Temple, we see his caricatural style shine. Each person in this image has a unique expression, even the lamb being carried away in the center of the scene. Matsys was not one for flattery—the faces of some of the merchants border on grotesque, though not all. He is careful to maintain these as human faces, ones we can identify with and see ourselves in.

The scene includes the range of characters noted in the Gospel story. Christ is in the center, driving out the merchants with his rope whip, three merchants receiving his blows. One of them, perhaps a money changer, lies on the ground, his table flipped, his coins scattered. Another merchant is just making his escape with a lamb on his back, while the most grotesque one on the left is trying to get away with his goods under his arms. In the back left, three distinguished-looking men observe—these are perhaps the Jewish leaders who debate with Christ about the Temple in John’s Gospel. To the right of the scene are three additional onlookers: one more merchant partially concealed by a sack, a seated figure, and a Temple-goer, whom we see in profile.

The setting evokes the idea of the Temple, but in fact it is a high-Gothic church contemporary to the artist’s time, perhaps the Cathedral of Antwerp, the town where the artist was most active. Likewise, the colorful clothes each character wears tell us that Matsys set this scene not in the Temple of first-century Jerusalem, but in his own 16th century. This is a not-so-subtle satirical commentary suggesting that perhaps the Church at his time needed Jesus’ cleansing. Yet, through the use of thoroughly human faces, it is not just the people of Matsys’s time that needed repentance and purification. The image invites us to see ourselves in it as well, to see and acknowledge honestly those areas of our lives needing a major cleaning. The variety of faces offer several entry points for us—the person on the ground, the one escaping, the one looking on, the one hiding, the one at a critical distance—where do we find ourselves in this im

Lenten Study, The Creeds, A Guide to Deeper Faith

When we say the Creeds (the Apostles’ Creed at baptisms and at Morning Prayer and the Nicene Creed when we celebrate the Eucharist), we are stating our belief in what the church believes, in faith, about God—that God is one being in three persons—that is, three “persons” within the one Godhead.

It’s easy to say these words without much thought because they are so familiar. And yet, they are the words that create community among Christian believers around the world, past, present, and future, the Apostles’ Creed being the most widely used of all of Christianity’s confessions of faith. These words are so important that they are permanently attached to our altar wall, along with the Ten Commandments and the Lord’s Prayer. The creeds not only bind us together in communities of faith, but these words, if taken into our hearts, can lead us to a deeper faith.

During this season of Lent, we will study these creeds, learning about how they came to be, what they mean to the Church, and we will also reflect on how they may help us grow in faith as Christians.

The study is scheduled for five Wednesday nights of Lent—Weds Feb. 21st, 28th, and March 6th, 13th, and 20th at 7PM on Zoom ID: 833 7014 5820 Passcode: 528834