I. Theme – Punishment and Grace

The lectionary readings are here or individually:

First Reading – Exodus 32:7-14

Psalm – Psalm 51:1-11

Epistle – 1 Timothy 1:12-17

Gospel – Luke 15:1-10

Today’s readings praise God’s merciful pursuit of God’s people even as they sin. The readings contrast punishment and grace. In Exodus God forgives the Israelites’ spiritual impatience and lack of trust that lead them to turn from God to an idol . The Epistle and Gospel highlight God’s graceful care, which encompasses the lost and sinful. Paul offers himself as an example of one found by God, transformed by the power of God’s mercy. In the gospel, Jesus tells stories that illustrate God’s great joy over each sinner who repents.

If God’s grace welcomes back the apostle Paul, despite his persecution of early Christians, will it welcome back the wealthy whose largess has come at the expense of the poor. Grace transforms the past, and opens us to become new creations. We still may have to face the consequences of the past; but grace leads to new behaviors and openness to expanded divine possibilities for ourselves and the good Earth.

Jesus makes clear in the Gospel that everyone falls within the shadow of salvation, regardless of their past behavior and place in society. What Jesus is doing is placing worth and value on what others had deemed worthless. The Jewish mystical tradition proclaims that when you save one soul, you save the world. This wisdom provides a creative lens through which to read the parable of the lost sheep.

Each one of us is made in the image of God; therefore, each one of us is worthy. Because of that, we are valued. We belong to God. And God will seek us out to the ends of the earth as a lost sheep, into all the cracks and darkness and lonely, lost places as a lost coin. We are not forgotten to God, even when we fall into despair, into addiction, into hopelessness.

II. Summary

First Reading – Exodus 32:7-14

Exodus 32:7-14 is from our second thread of the readings this season, in which the theme of God fulfilling the covenantal promises made with the people prevails.

Early in their journey from slavery in Egypt to the promised Land, God’s people became restless and untrusting

When Moses led the Hebrew slaves out of Egypt, they did not go very long or very far before they lost confidence in Moses and in the path on which he was leading them. They were camped in the Sinai desert at the foot of a mountain, while Moses was up the mountain receiving extensive instructions from the Lord. The people grew restless, then nostalgic even for the ways of their Egyptian former masters. They melted jewelry and formed an idol (or a token of rebellion against Moses) from it in the shape of a calf, then worshiped it with exuberant ceremony. The golden calf would be followed as their god. Of course the Lord is outraged, and Moses has to intervene, reminding the Lord of the covenant, lest the Lord revoke it.

This reading begins a section on Israel’s sin and God’s forgiveness (chaps. 32–34). It serves both as a narrative sequel to the giving of the law on Mt. Sinai and as a spiritual reflection upon Israel’s repeated apostasy from the time of the exodus to the exile. The worship of the golden calf signified an adoption of the Canaanite rites of Baal. It may represent not a false god but a challenge to Moses as mediator between the people and God.

In view of the lord’s anger, Moses intercedes for the people. He reminds God that it was God’s actions that brought them out of slavery into the wilderness. He reminds the lord of the covenant that these are God’s own people, that God’s name is now bound up with theirs and that God had promised Abraham, not Moses, many descendants.

Moses uses Egypt in a unique way in his argument with G-d. “What will the Egyptians think?” And to this he adds significant names: Abraham, Isaac, and Israel (Jacob). To these God had made significant promises of continuity and a future

God changes God’s mind about destroying them all, remembering the covenant to Abraham and Sarah and to their descendants forever. Like wedding vows, God will be their God, through good times and bad, and will never abandon them completely or destroy them. Although Moses effectively ends the conversation with God’s repentance, he seems to be unable to answer to the evidence that God sets before him.

Psalm – Psalm 51:1-11

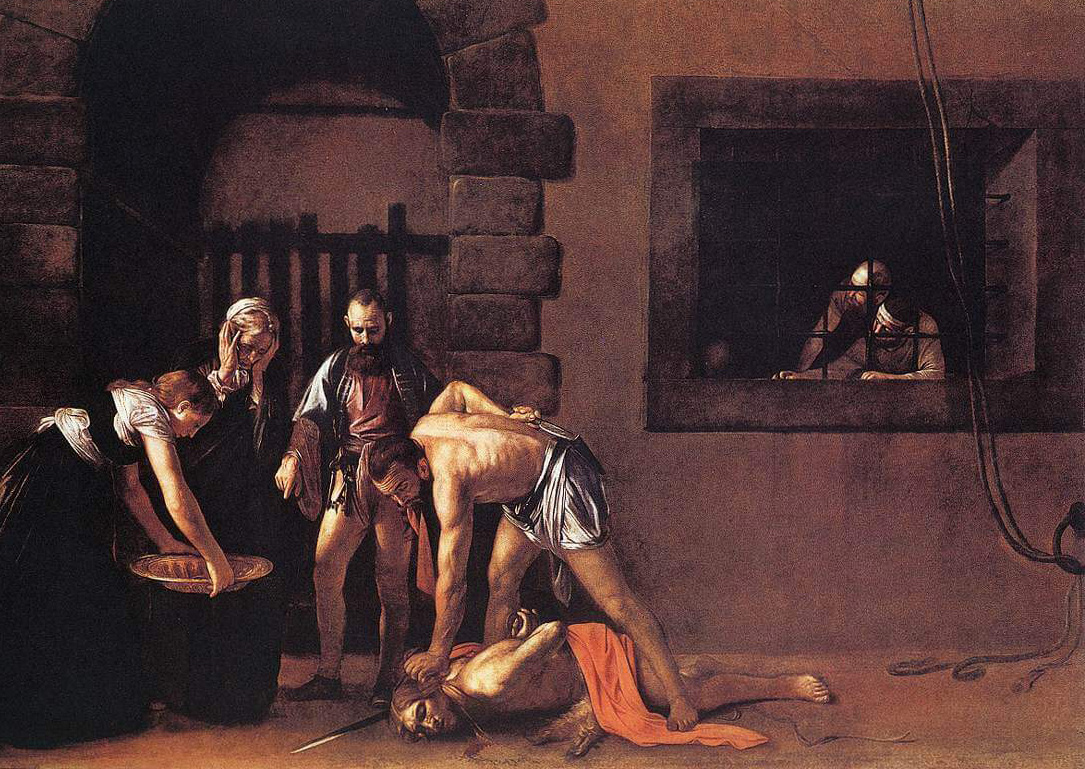

This is one of the great penitential psalms. The psalm’s title, added later, ascribes this psalm to David during the time of his repentance for the seduction of Bathsheba and the murder of her husband, Uriah (2 Samuel 11:1–12:25).

Psalm 51:1-10 is the opposite of Psalm 14: in this psalm, the singer acknowledges their own sin, their own turning away from God, and desires reconciliation and forgiveness and restoration. The singer famously asks for a new, clean heart, and a new and right spirit within them, to guide them on the path that leads to God.

The constant hope and the goal of the covenant people was to become a community in right relationship with God and one another. Sin was understood as whatever disordered relationships – it is everywhere and at every time. The psalmist seeks not merely the removal of guilt, but the restoration of a right relationship to God. Verse 4 does not exclude sin against one’s neighbor, for that was also understood as an offense against God because it broke down the covenant relationships desired by God.

The psalm also speaks to the ubiquity of God’s knowledge of us – in the hidden knowledge within us. In verse 9 we begin to feel relief. “Purge me with hyssop” refers to the priest’s sprinkling the people with the blood of the sacrifice, or as in Numbers 19:18-22, where it refers to cleansing with water. The point is made with both images – the psalmist seeks redemption and forgiveness, and it is given so that it can be heard and be the cause of praise. The verse regarding “the right spirit” might call us all back to creation again, where the Spirit reboots us into righteousness and holy living.

This psalm has a place in the Liturgy for Ash Wednesday, where it serves as a psalm underscoring the penitential nature of the day. The introduction to the psalm serves as a poignant notice as well:

Epistle- 1 Timothy 1:12-17

Paul enjoyed God’s mercy, and uses his experience as an example for potential believers.

This selection begins a seven-week series of readings from two letters traditionally attributed to St. Paul. 1 and 2 Timothy, along with Titus, are called the pastoral epistles because of their emphasis on the proper ordering of the administration and worship of the Church. Many scholars today believe that these letters were not written by Paul himself but by a later follower. Such an author may have pieced together some of Paul’s personal letters and added material that presented oral Pauline teaching which addressed later situations.

Today’s reading is a thanksgiving for Paul’s conversion, especially as it serves as a paradigm of God’s mercy in the conversion of all “sinners.” A phrase characteristic of Paul’s emphasis on tradition is “the saying is sure” (v. 15) indicating a quotation from familiar teaching or hymns.

The author intends for the reader/hearer to understand what Paul stood for, and to see in his own story, the story of Christ’s grace intended for them as well. The exaggerated list of vices that describe Paul’s former life (“blasphemer”, “persecutor”, and “man of violence”) is meant to highlight Paul’s message of grace, which is intended for the reader, ostensibly Timothy. Thus Paul serves as the primary example of grace that will abound in those who follow the Gospel of Jesus.

This passage is a beautiful statement of thanksgiving to Jesus who is the one who called the writer into this ministry, using him despite of, and because of, his faults and shortcomings to be a witness to God. Christ came into the world to save sinners. The writer is grateful for God’s blessings, grace and mercy, and that because of God’s grace and mercy the writer is able to use his whole life as a witness of Jesus Christ and of Christ’s faith and love.

The closing is very interesting and is perhaps the remains of an ancient doxology that was used in early Christian worship.

Gospel – Luke 15:1-10

Luke writes his gospel for a community undergoing transition. Jesus’ original followers were poor Jews. But now the situation shifts so that Luke’s audience is composed primarily of respectable people who have an annoying way of looking down on others for a variety of reasons.

Luke 15:1-10 contain the first two of three parables in this chapter—the most famous, the Parable of the Prodigal Son, is not included in the lectionary this time. But these first two parables of the Lost Sheep and the Lost Coin are also important. Here Jesus is gathered with both the sinners (tax collectors and their ilk) and the supposedly righteous (the Pharisees and the scribes). What Jesus does and says will come under the close scrutiny of both camps.

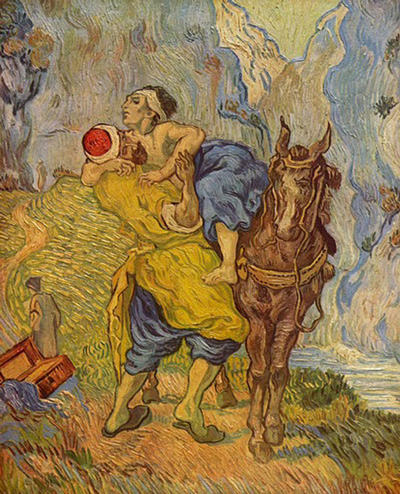

Jesus was eating with sinners, welcoming them, and that some of the religious leaders were complaining about it. In both of these parables, the protagonist pays attention to something that normally would be forgotten about soon after—a lost sheep, a lost coin. It would have been ridiculous to leave 99 sheep behind to go after one lost sheep. Losing just one was probably a miracle that you didn’t lose more. Same with losing a coin. If you lost a $100 bill but had 9 more of them, you might be a bit angry that you lost it, but you would get over it soon. You certainly wouldn’t be going out and inviting your neighbors to celebrate once you found it

Luke 15 describes God’s joy at homecoming of sinners. The trilogy of Luke describes three states of being lost: wandering off ignorantly, being lost in the shuffle, and choosing to go astray. None of these states is beyond God’s redemption. At any moment we can turn around to awaken to God’s grace

Jesus uses the unwearied search of a shepherd for a lost sheep or of a poor woman for a lost coin as an image for God’s unchanging love toward the sinner. God’s constant seeking-out of the lost is manifested in Jesus’ redeeming ministry. God’s love takes the initiative; the sinner’s response is repentance. But rejoicing is the central note of these parables, for there is no mention of penitence.

Like Nathan, who convinces David of his sinfulness, by getting him to identify with the poor neighbor of his story (see Psalm 51, above), so Jesus seeks to have the hearer, whether sinner or scribe, to identify with the one who has lost either sheep, coin, or son

There is also the connection in this parable to the others. The shepherd risks the flock, to some degree, by leaving them to find the lost sheep. But, perhaps more importantly, the ninety nine cannot be fully saved apart from the lost sheep. They will remain ninety nine and not experience the wholeness of the perfect number, one hundred. Salvation is relational; our salvation is connected to the well-being of others. We cannot be complete without the salvation of others. The joy of heaven is found in the welcoming home of every soul.

The two parables in today’s reading make the same point. They answer those who criticized Jesus for having any dealings with the outcast and despised. It was a strong ancient principle, especially among the Pharisees, that one should not associate with sinners. “Sinners” were both those who led immoral lives and those whose occupations were considered sure to lead them into immorality—tax collectors, shepherds, etc. “Sinners” could not hold office or act as legal witnesses.

Jesus makes clear that everyone falls within the shadow of salvation, regardless of their past behavior and place in society. What Jesus is doing is placing worth and value on what others had deemed worthless. The Jewish mystical tradition proclaims that when you save one soul, you save the world. This wisdom provides a creative lens through which to read the parable of the lost sheep.

Both parables speak to the implicit value of things. People—human beings, their very lives—are valuable to God, every single one. And when society starts saying you’re worthless, you might start believing it—and ending up in addiction, depressed, and feeling completely useless to the world. But Jesus says “You are valuable—You are precious to God.” Jesus would rather leave the 99 who know who they are to find the one that has been rejected and left for dead. Jesus would rather spend all the time looking to find one who was lost than to forget and move on. People are more valuable than lost coins or even lost