Sermon, Proper 17, Year C, 2022 Proverbs 25: 6-7, Psalm 112, Luke 14:1, 7-14

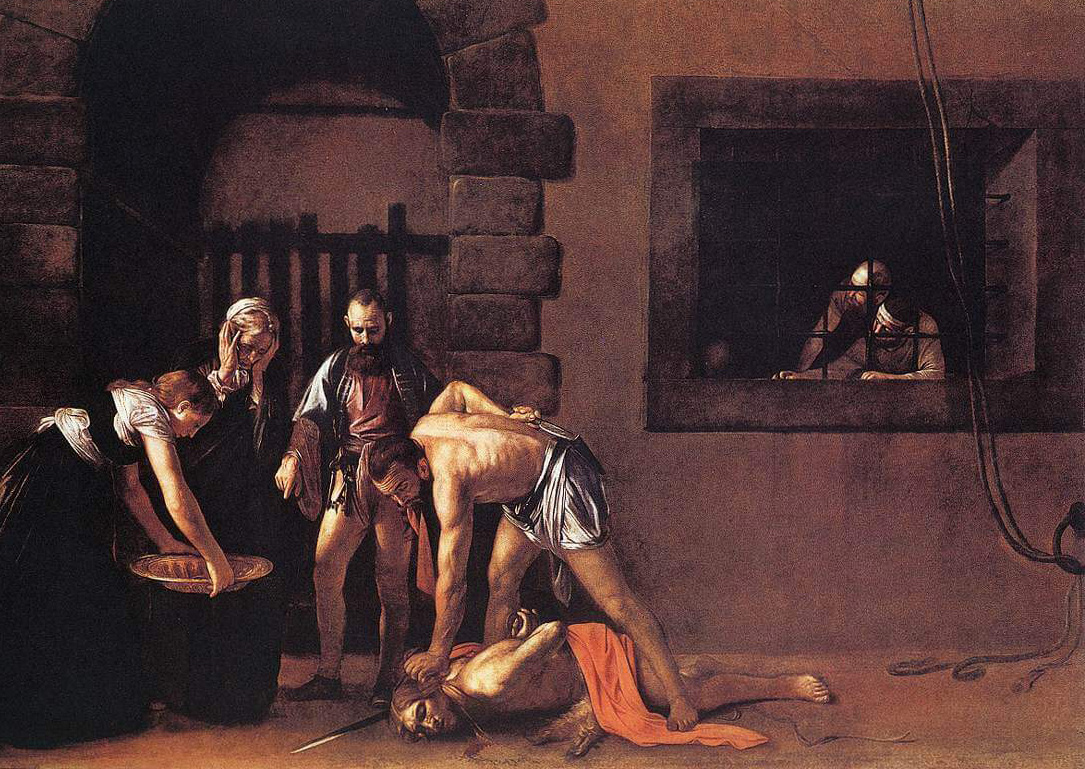

“Supper at Emmaus”- Caravaggio

In today’s gospel, Jesus tells us about how we are to come to our true place in the reign of God and find ourselves seated at God’s “welcome table.”

In this story, Jesus is eating a meal on the Sabbath with a leader of the Pharisees. The first verse of this passage says that they were watching Jesus closely. I’m assuming that “they” were the group of Pharisees who would have been invited to this meal.

Jesus watches the Pharisees take their places at the meal. Where they sat was quite important, for the seating indicated where people stood within the group, who were the most honored, and who were the least important.

The Pharisees were strict followers of Jewish tradition. The more they followed the tradition, the better they considered themselves to be. They judged one another on their accomplishments in the department of law keeping. And those who were the best were the ones chosen to sit in the place of honor at banquets.

Inevitably the Pharisees had come to believe that their relationships with God were determined by how well they kept the laws, and that they earned God’s favor by keeping God’s commandments.

We fall into the same trap ourselves. We try to live by God’s laws. We try to love God and to care for others. We are proud of our accomplishments. We are proud of being good people. But that proudness we develop can adversely affect our relationship with God, and with other people.

Here’s an example. Years ago, Easter Sunday had at last arrived at St George’s in Fredericksburg. The scent of lilies filled the church, exquisitely arranged flowers delighted our eyes, the choir, accompanied by trumpets, sounded like a heavenly chorus—what a grand way to celebrate our Lord’s resurrection. How proud I was to be there, proud of being a good Christian on this day, along with all the other good Christians who filled every pew.

And then my rejoicing was interrupted.

For who should be the lector that day but a woman in our congregation who was well known for her struggles in life and who wasn’t the best reader either.

I’m ashamed to admit that I thought to myself, “I can’t believe that she is reading on Easter Sunday of all days! She isn’t worthy of that honor. Someone who is better than she should be the one up there in front of all these people. I am worthier than she is! Why didn’t I get chosen to read today?” And then I instantly felt guilty and ashamed for this proud thought.

I have mulled over that incident many times in the years that have passed since then. I had gotten caught up in trying to prove myself to God and to everyone else, trying to prove that I was worthy of a place of honor. I was trying to earn my way to God’s table. I had not taken to heart the wisdom of what Jesus had to say in today’s gospel.

Maybe the Pharisees who listened to Jesus that day took the parable he told literally. Maybe at that very meal they had observed the host asking someone to move so that someone more important could sit near the host. And so Jesus underscored what they had all just seen by reminding them of the verse in Proverbs that says “It is better to be told, “Come up here,” than to be put lower at the table. Who would want to be embarrassed in such a public way?

But there’s more to the story Jesus tells than just what happens on the surface of the story.

Jesus is reminding those with ears to hear that our true place in God’s reign is not up to us. No matter how hard we try, we cannot earn the seat of honor at the heavenly banquet, or even a place at all.

Instead, our place at the table in God’s house is entirely up to God’s gracious love and mercy. And we want to put forth our best effort out of gratitude for God’s gracious love and mercy at work in our lives.

Instead of working on earning a place of honor, instead of trying to prove our worthiness, our assignment is simply to trust in the Lord instead of ourselves, to fear the Lord, to take delight in the Lord’s commandments, to be merciful and full of compassion, and to be generous and just, as today’s psalmist explains.

Our assignment is to be humble, just like Jesus was in his life on earth.

In his letter to the Philippians, Paul reminded his listeners that Jesus himself, God incarnate, did not cling to equality with God, but humbled himself, becoming a servant, and became obedient to death, even death on a cross.

To be a follower of Jesus is to cultivate humility, and to be a servant to God and to those around us.

Remember the parable Jesus told that we heard a few weeks ago, in which the watchful slaves are to be dressed for action and to have their lamps lit, to be like those who are waiting for their master to return from the wedding banquet, so that they may open the door for him as soon as he comes and knocks.

And then when the master arrives, he blesses the alert slaves. Just as Jesus did when he washed the feet of his disciples at the last supper, this master will come in, put on his apron, and have the servants sit down to eat, and the master will serve them!

That is shocking, that God would choose to wait on us!

And even more shocking, God invites everyone to the table, not just the worthy few who may, in the eyes of this world, be the deserving ones.

Jesus reminds the Pharisees, and us, of that aspect of God’s unconditional love for all of us in the second half of today’s gospel, when he tells the host, “Next time, don’t invite the ones who can and will repay you. Instead, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame and the blind.” They can’t repay you. But God, the only one who can bless us, will bless you because what you have done for those who cannot repay you have done for God.

To offer this grace and mercy to all that is around us is not about earning God’s favor. Offering grace and mercy to the other is an act of gratitude and thanksgiving to God—God, who loves us enough to welcome us to the table even when we are poor in spirit, even when we are crippled physically or spiritually or emotionally, even when we are too weak to get up and walk through another day, even when we can’t even see that God is right there before us, inviting us to God’s table, even when we struggle to be unselfish and hesitate to invite those who cannot repay us to come on in.

So how are we to come to our true place in God’s reign?

To humbly trust in the Lord instead of in ourselves and our accomplishments.

And to live in gratitude by sharing God’s undeserved hospitality, knowing that God embraces all of us and all things in God’s great circle of love, and invites us all to God’s welcome table.