This is one of the most practical Bible lessons.

“Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life? This is a basic, universal question that is asked by almost all human beings, even today. In Mark and Matthew, the question is more of a Jewish question. That is, “What is the greatest/first commandment of the law?” Mark and Matthew were asking a fundamental Jewish question; Luke was asking a fundamental universal question.

Luke was written to a larger world which he knew as a follower of Paul. This was the first time the idea of Dt 6:5 (“Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength”) being combined with Leviticus 19:18 (“Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against anyone among your people, but love your neighbor as yourself.”)

Jesus is challenged by a lawyer. The lawyer’s presence and public questioning of Jesus shows the degree of importance his detractors are placing on finding a flaw they can use. The lawyer is trying to see if there was a distinction between friends and enemies. Luke in the Sermon on the Plain (Luke 6:20 “But I tell you who hear me: Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you.”) had eliminated the distinction and the lawyer was trying to introduce it again. As Jesus’ influence with the crowds continues to grow, the alarm of the religious establishment grows as well.

His first question is “what must I do to inherit eternal life.” Jesus answers, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself.” The lawyer follows up with a second question, also a very good one. If doing this, i.e., loving God and loving neighbor as oneself, is a matter of eternal life, then defining “neighbor” is important in this context. The lawyer, however, in reality, is self-centered, concerned only for himself.

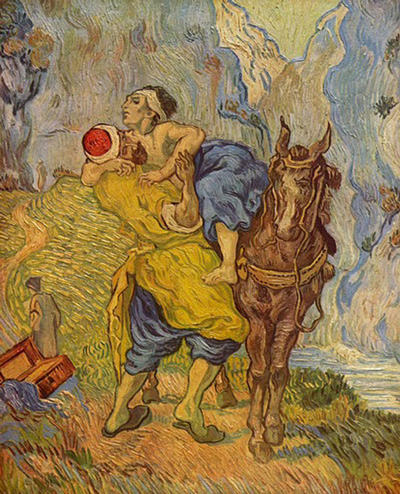

Jesus shifts the question from the one the lawyer asks — who is my neighbor?–to ask what a righteous neighbor does. The neighbor is the one we least expect to be a neighbor. The neighbor is the “other,” the one most despised or feared or not like us. It is much broader than the person who lives next to you. A first century audience, Jesus’ or Luke’s, would have known the Samaritan represented a despised “other.”

Read more: The Good Samaritan – ‘What must I do to inherit eternal life?’Of the four characters in this story (besides the robbers and the victim) – the lawyer, levite, priest and Samaritan – the first three were known in Jewish society. The Samaritan is the outsider.

The idea of being a “Good Samaritan” would have been an oxymoron to a first century Jew. During an ancient Israeli war, most of the Jews living up north in Samaria were killed or taken into exile. How can the Samaritans be anything but “bad”? Jews would do anything to avoid these people. However, a few Jews, who were so unimportant that nobody wanted them, were left in Samaria. Since that time, these Jews had intermarried with other races. They were considered half-breeds by the “true” Jews. They had perverted the race. They had also perverted the religion.

Note also that the Samaritan acts not to receive anything for himself (like self-justification). He responds to the needs of the man in the ditch and his actions cost him — time and money. The others can’t go beyond their limited role in society. The levite can’t touch the injured because of laws against uncleanness. The priests (Pharisees) are more concerned with rules and structures. We must look beyond the mores of society.

The verbs used with the Samaritan are worth emulating: to have compassion others; to come (near) to others; to care for others; to do mercy to others. It is not enough just to know what the Law says, one must also do it. To put it another way, it is not enough just to talk about “what one believes,” but “what difference does it make in my life that I believe.”

The man in the ditch may represent us. Brian Stoffregen quotes Bernard Scott in Jesus, Symbol-Maker for the Kingdom. “Grace comes to those who cannot resist, who have no other alternative than to accept it. To enter the parable’s World, to get into the ditch, is to be so low that grace is the only alternative. The point may be so simple as this: only he who needs grace can receive grace.. all who are truly victims, truly disinherited, have no choice but to give themselves up to mercy.” And we are victims in our own way.

He goes on to say “the parable of the Good Samaritan may be reduced to two propositions: In the Kingdom of God mercy comes only to those who have no right to expect it and who cannot resist it when it comes. Mercy always comes from the quarter from which one does not and cannot expect.”

Stoffregen says “I have usually taken the second interpretive approach to this text. We are the ones in the ditch and the Samaritan represent God — God who is both enemy and helper. Our sin makes God our enemy. Yet, in the parable, the “enemy” gives new life to the man in the ditch. The “enemy” expends his resources (apparently unlimited) for the care of the half-dead man.

“The problems with the lawyer is that he couldn’t see God as his enemy. He hadn’t recognized the depth of his own sinfulness. (He wants to justify himself and probably had a bit of pride that comes along with that.) He was too strong and healthy. He assumes that he has the ability to do something to inherit eternal life. He assumes that he can do something to justify himself. He is not helpless in the ditch. He thinks he doesn’t need God’s grace.

“God also gets into the ditch of the dead. On the cross, God died. There is the resurrection “donkey” who transports us to the heavenly “inn” where there is complete recovery from all pain and suffering.”

“I also noted in this sermon that at times we might identify with the innkeeper. In the parable, the Samaritan used the innkeeper to continue the healing process the he had started. The Samaritan promised to provide everything that the innkeeper would need to care for this man. Sometimes God helps us out of the ditch directly. Sometimes God uses other people.”

In the end our neighbor is everyone.

Jesus said to him, “You have answered rightly. Do this and you will live. We don’t repeat the words – we need live them as they had at the time. It is part of living a transformed life in the Kingdom away from structure of society that inhibit us and put blinders on us.”