Recent Articles, Pentecost 5, July 13, 2025

“Summer at St. Peter’s”

Pentecost 5 – Good Samaritan

Pentecost 5 – Good Samaritan

Lectionary Pentecost 5, Year C

Commentary Pentecost 5

Visual Lectionary Pentecost 5

The Gospel in July, 2025

The Good Samaritan

5 minute podcast-the Good Samaritan

The Good Samaritan – ‘What must I do to inherit eternal life?’

Background of the Good Samaritan

Van Gogh’s Depiction of the Good Samaritan

Martin Luther King on the Good Samaritan

Focus on Neighbor, Compassion, Reversal

Here and There on the Web – miscellaneous discoveries

Anything but Ordinary! Ordinary Time

Green is for growth in Ordinary Time

Lectionary, Proper 10, Pentecost 5

I. Theme – God’s call challenges us to obedience, compassion and action for justice

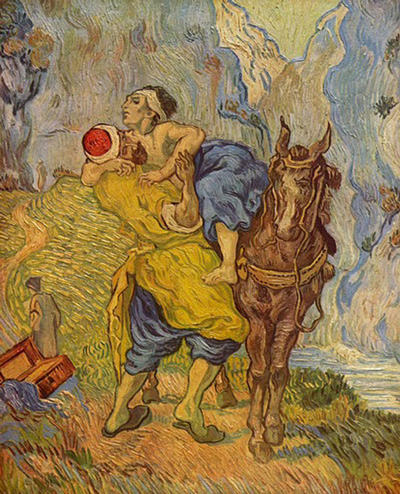

"The Good Samaritan" – Van Gogh (1890)

The lectionary readings are here or individually:

First Reading – Deuteronomy 30:9-14

Psalm – Psalm 25:1-9

Epistle – Colossians 1:1-14

Gospel – Luke 10:25-37

Today’s readings focus on God’s call challenging us to obedience, compassion and action for justice. In Deuteronomy (Track 2), Moses assures the people that God’s call to obedience is not too difficult nor is it hidden. Paul writes that Christ, the image of the invisible God, is our Creator, Sustainer and Reconciler. Jesus answers a lawyer’s question by telling the story of the Good Samaritan.

What we say about ourselves is not nearly as important as how we live out what we say—how we live out our lives with Christ. We are called by God throughout scripture and tradition to care for the poor, the outcast, the oppressed, and the marginalized—but throughout our history and scripture, we have found ways to make excuses. We have put ourselves before others and have justified our way of life, while others around us and in the world continue to suffer. We cannot remain ignorant of the struggles of others. Eventually, justice catches up to us

Moses warned the people in the wilderness, and they did not listen. Jesus questions the lawyer who wants the right answer to be given, who wants to speak aloud the truth, and helps him to realize that it is about a love that shows mercy, a way of living towards others. How are we living out our faith? Are we just saying what we believe in? Is it more important to have the right statements of faith, or is it more important to do what Jesus has called us to do and live out our faith?

How often have we passed by persons in need or deferred social involvement to keep our own schedule ? We are not bad persons either; we simply place our broad spectrum vocational callings ahead of the concreteness of God’s call in the present moment.

Our challenge is to grow in stature, so that we can creatively and lovingly balance our personal and institutional responsibilities, including our self-care and care for families and congregations, with the unsettling challenges to go beyond our immediate responsibilities so that we may become God’s partners in healing the world. Jewish mystics remind us that to save one soul is to save the world. From a God’s eye view, this means to care for our loved ones and ourselves as well as those who are loved by God and beyond the walls of our communities. This will lead to agitation but our agitation will find completeness and comfort in feelings of wholeness which emerge when we join our well-being with the well-being of our most vulnerable local and global companions.

5 minute podcast about the “Good Samaritan”

This podcast was generated from 8 sources on this website about the “Good Samaritan” Gospel passage.

Visual Lectionary Vanderbilt, Fifth Sunday of Easter, Year C

Click here to view in a new window.

The Good Samaritan – ‘What must I do to inherit eternal life?’

This is one of the most practical Bible lessons.

“Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life? This is a basic, universal question that is asked by almost all human beings, even today. In Mark and Matthew, the question is more of a Jewish question. That is, “What is the greatest/first commandment of the law?” Mark and Matthew were asking a fundamental Jewish question; Luke was asking a fundamental universal question.

Luke was written to a larger world which he knew as a follower of Paul. This was the first time the idea of Dt 6:5 (“Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength”) being combined with Leviticus 19:18 (“Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against anyone among your people, but love your neighbor as yourself.”)

Jesus is challenged by a lawyer. The lawyer’s presence and public questioning of Jesus shows the degree of importance his detractors are placing on finding a flaw they can use. The lawyer is trying to see if there was a distinction between friends and enemies. Luke in the Sermon on the Plain (Luke 6:20 “But I tell you who hear me: Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you.”) had eliminated the distinction and the lawyer was trying to introduce it again. As Jesus’ influence with the crowds continues to grow, the alarm of the religious establishment grows as well.

His first question is “what must I do to inherit eternal life.” Jesus answers, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself.” The lawyer follows up with a second question, also a very good one. If doing this, i.e., loving God and loving neighbor as oneself, is a matter of eternal life, then defining “neighbor” is important in this context. The lawyer, however, in reality, is self-centered, concerned only for himself.

Jesus shifts the question from the one the lawyer asks — who is my neighbor?–to ask what a righteous neighbor does. The neighbor is the one we least expect to be a neighbor. The neighbor is the “other,” the one most despised or feared or not like us. It is much broader than the person who lives next to you. A first century audience, Jesus’ or Luke’s, would have known the Samaritan represented a despised “other.”

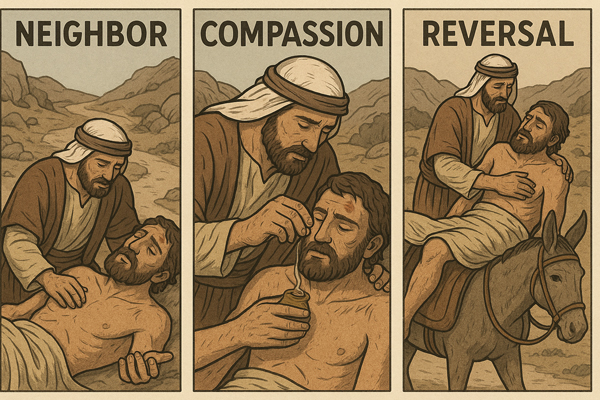

The Good Samaritan – Neighbor, Compassion, & Reversal

Focus on Neighbor:

The Parable of the Good Samaritan is a pivotal moment in Luke’s Gospel, where Jesus radically redefines the prevailing understanding of ‘neighbor.’ The lawyer’s initial question, ‘Who is my neighbor?’ (v. 29), likely stemmed from a desire to limit his obligation to those within his own community or religious group. However, Jesus shatters these comfortable boundaries. By choosing a Samaritan – a person ethnically and religiously despised by the Jews – as the hero, Jesus forces his audience to confront their prejudices. The ‘neighbor’ is not defined by proximity, shared heritage, or religious affiliation, but by one’s capacity for compassion and action in the face of another’s need, regardless of who that ‘other’ might be. This parable challenges us to look beyond our ‘in-groups’ and extend love and practical help to anyone we encounter who is suffering, even our perceived enemies.

Focus on Practical Compassion and Costly Love:

Beyond the theological implications, the Good Samaritan offers a powerful blueprint for practical, costly love. Notice the detailed actions of the Samaritan: he ‘had compassion,’ ‘bandaged his wounds,’ ‘poured on oil and wine,’ ‘set him on his own animal,’ ‘brought him to an inn,’ and ‘took care of him’ (vv. 33-34). Crucially, he also made a financial commitment, giving the innkeeper ‘two denarii’ and promising to pay more if needed (v. 35). This isn’t just about feeling pity; it’s about active, self-sacrificial involvement. The priest and the Levite, by contrast, prioritized ritual purity or personal convenience over the desperate need before them. The parable underscores that true neighborliness isn’t just a sentiment, but a tangible commitment that often involves inconvenience, expense, and a willingness to step outside our comfort zones to alleviate another’s suffering.

Focus on the Ironic Reversal and Challenging Self-Righteousness:

One of the most striking elements of the Good Samaritan parable is its ironic reversal of expectations, designed to challenge the self-righteousness of Jesus’ audience, including the inquiring lawyer. The figures who would have been considered ‘pious’ and ‘righteous’ – the priest and the Levite – utterly fail in their moral duty. It is the Samaritan, a member of a despised and heretical group, who embodies true righteousness and fulfills the spirit of the Law. This reversal is profoundly uncomfortable because it upends conventional wisdom and exposes the hypocrisy that can lurk beneath outward religious observance. Jesus essentially asks, ‘Who truly lived out the command to love God and neighbor in this scenario?’ The answer is startlingly clear: not the religious elites, but the one they looked down upon. This forces us to examine our own assumptions about who is ‘worthy’ or ‘unworthy’ of our compassion and reminds us that true faith is demonstrated through merciful action, not just adherence to rules or social status.

Martin Luther King on the “Good Samaritan”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his last speech in support of the striking sanitation workers at Mason Temple in Memphis, TN on April 3, 1968. Toward the end of the speech he introduces the Good Samaritan parable

“Let us develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness. One day a man came to Jesus; and he wanted to raise some questions about some vital matters in life. At points, he wanted to trick Jesus, and show him that he knew a little more than Jesus knew, and through this, throw him off base. Now that question could have easily ended up in a philosophical and theological debate. But Jesus immediately pulled that question from mid-air, and placed it on a dangerous curve between Jerusalem and Jericho. And he talked about a certain man, who fell among thieves. You remember that a Levite and a priest passed by on the other side. They didn’t stop to help him. And finally a man of another race came by. He got down from his beast, decided not to be compassionate by proxy. But with him, administering first aid, and helped the man in need. Jesus ended up saying, this was the good man, this was the great man, because he had the capacity to project the “I” into the “thou,” and to be concerned about his brother. Now you know, we use our imagination a great deal to try to determine why the priest and the Levite didn’t stop. At times we say they were busy going to church meetings—an ecclesiastical gathering—and they had to get on down to Jerusalem so they wouldn’t be late for their meeting. At other times we would speculate that there was a religious law that “One who was engaged in religious ceremonials was not to touch a human body twenty-four hours before the ceremony.” And every now and then we begin to wonder whether maybe they were not going down to Jerusalem, or down to Jericho, rather to organize a “Jericho Road Improvement Association.” That’s a possibility. Maybe they felt that it was better to deal with the problem from the causal root, rather than to get bogged down with an individual effort.

“But I’m going to tell you what my imagination tells me. It’s possible that these men were afraid. You see, the Jericho road is a dangerous road. I remember when Mrs. King and I were first in Jerusalem. We rented a car and drove from Jerusalem down to Jericho. And as soon as we got on that road, I said to my wife, “I can see why Jesus used this as a setting for his parable.” It’s a winding, meandering road. It’s really conducive for ambushing. You start out in Jerusalem, which is about 1200 miles, or rather 1200 feet above sea level. And by the time you get down to Jericho, fifteen or twenty minutes later, you’re about 2200 feet below sea level. That’s a dangerous road. In the days of Jesus it came to be known as the “Bloody Pass.” And you know, it’s possible that the priest and the Levite looked over that man on the ground and wondered if the robbers were still around. Or it’s possible that they felt that the man on the ground was merely faking. And he was acting like he had been robbed and hurt, in order to seize them over there, lure them there for quick and easy seizure. And so the first question that the Levite asked was, “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” But then the Good Samaritan came by. And he reversed the question: “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?”

“That’s the question before you tonight. Not, “If I stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to all of the hours that I usually spend in my office every day and every week as a pastor?” The question is not, “If I stop to help this man in need, what will happen to me?” “If I do not stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to them?” That’s the question.

“Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge to make America what it ought to be. We have an opportunity to make America a better nation. And I want to thank God, once more, for allowing me to be here with you.”

Van Gogh’s Depiction of the Good Samaritan

Vincent Van Gogh’s dynamic and intimate portrait of the Good Samaritan is based on the French painter Eugene Delacroix’s similar painting. Van Gogh painted his own version of Delacroix’s The Good Samaritan while recuperating at the asylum of Saint-Rémy after suffering from two mental breakdowns in the winter of 1888-89.

At the time, Van Gogh was feeling spent and fragile and this sense of helplessness colors both figures at the heart of the painting. The broken and attacked man can barely get up on the horse. His muscles appear limp, depleted of any strength that could help him sit upright. All the man appears capable of is clinging to his rescuer. Likewise, the Samaritan seems to be barely able to summon up the strength to lift the man on the horse. By imbuing the painting with his own brokenness, Van Gogh creates a moving depiction of Christ’s solidarity with us in our human weakness. Christ humbles himself, taking on the form of a slave (Phil 2:7). And we, like this robbed man, can do nothing without Christ who strengthens us (Phil 4:13).

In some of the earliest interpretations of the parable by early Church theologians, most famously by Augustine, the Good Samaritan is an image of Christ. The two coins with which the Samaritan pays the innkeeper are the two commandments: to love the Lord Our and to love our neighbor as ourselves. During this Lenten season, we strive to love God more through purifying our lives of distracting loves of lesser things, and we strive to love our neighbor more through positive actions of charity and almsgiving.

As we meditate on this image of the Samaritan lifting up the weak robbed man, let us ponder what weaknesses we need Christ to heal in us. How is Christ seeking to reach us, even in our weakness? And how, through acts of almsgiving, can we be Good Samaritans for our neighbors in need this Lent?

On May 8, 1889, exhausted, ill, and out of control, Vincent Van Gogh committed himself to St. Paul’s psychiatric asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, a small hamlet in the south of France. A former monastery, the sanitarium was located in an area of cornfields, vineyards and olive trees. There Van Gogh was allowed two small adjoining cells with barred windows. One room he used as his bedroom, and the other was his tiny studio. While there, Van Gogh not only painted the surrounding area and the interior of the asylum, he also copied paintings and drawings by other artists, making those paintings his own through modifications he made to the painting’s composition, the colors and, of course, the brush strokes.

One of the artists whose works Van Gogh copied and modified was the Dutch Gold Age painter Rembrandt van Rijn. The Good Samaritan by Rembrandt drew Van Gogh’s attention: in which a Samaritan man hoists a wounded man with a bandaged head onto a horse to be taken to an inn for recovery.

When Van Gogh was admitted to the sanitarium in St Remy de Provence, he had become so difficult, so sick that the townspeople of Arles, where he had been living and painting had given him the name “the red-headed madman.” After a psychotic break during the visit of fellow artist Paul Gauguin, Van Gogh was all but put out of the town. With the help of a couple of people, he eventually made his way to the sanitarium in St Remy de Provence where he copied and modified Delacroix’s painting of The Good Samaritan.

If viewers were to see the two paintings – Rembrandt’s and Van Gogh’s side by side – the first thing that would strike you is the light in Van Gogh’s painting and the darkness in Rembrandt’s. Though not sharing the bright colors of his paintings in Arles, Van Gogh’s painting of The Good Samaritan, is well lit which means we can make out things more clearly in the painting.

Compassion without Boundaries -Background of the “Good Samaritan” in Luke from author Alexander Shaia

Some background of the Gospel of Luke provides insight of why this story appears in this gospel and no others. Luke wrote in the 80’s AD after both Matthew and Mark (and before John). Jesus resurrection was 50 years earlier. He wrote it in Antioch in Turkey at a time when Christianity was expanding to the Gentiles all throughout the Mediterranean. How was Christianity to unite these peoples ?

The issues are taken up in The Hidden Power of the Gospels: Four Questions, Four Paths, One Journey by Alexander Shaia.

“Nero had executed the Jewish Christus followers of Rome twenty years earlier, although persecution had not extended to Christus believers throughout the rest of the empire at that time. Then in 70 CE, Vespasian leveled the Great Temple of Jerusalem and massacred all its priests, throwing Judaism into total disarray. In the steps that religion took to survive, a process began that still resonates in the lives of Christians and Jews.

“The slaughter resulted in a complete lack of religious authority. The Pharisees, educated teachers of Jewish religious law but not officially connected to the Temple, stepped into the vacuum. By the mid-80s CE, the time of Luke’s gospel, their role had significantly increased. In many Jewish communities, their voices rose to roles of clear leadership. In others, they represented merely one of many voices struggling to advise how best to move forward in the face of great loss. Eventually, the Pharisees became the primary voice of the Jewish community, reunifying the people in the absence of the Temple and its priests—but not before Luke began to write.”

And as part of their ascension “The Pharisees advocated for the removal from Judaism of all variant sects who believed that the Messiah had already come. Chief among these were the “Followers of the Way”’ (the Christus sect), who maintained that the Messiah had arrived for the salvation of all people, not just Jew

“They carried pain, and some of them likely had a touch of arrogance attached to their lingering resentments. They had also migrated all over the Mediterranean basin, which presented them with persecution from another quarter. The Roman government was more than nervous about the Christus followers—it was terror-stricken. “The fear of this message led to its oppression of the Christus communities—and the persecution increased steadily.

“The fear of this message led to its oppression of the Christus communities—and the persecution increased steadily.

“Although some scholars believe that the Gospel of Luke was written to a high Roman official in defense of Christianity, others think it was a teaching written in Antioch designed to be distributed among these burgeoning communities across the Mediterranean world.

“In Hebrew teachings, “heart” implies a unitive aspect of one’s humanity that is greater than mere emotion—encompassing body, feelings, will, intuition, and thought—everything but soul.

“How were the nascent “Followers of the Way” to move forward in the face of being cursed by the Pharisees, abandoned by most of their Jewish friends, and oppressed by the Roman Empire? How could they deal with the hurt and resentments that threatened to poison their lives and divide their families? Should they verbally dispute and defend themselves against each hurt? Should they take up arms and fight? Should they hold to traditional practices?

“Luke draws a stark spiritual line, using his gospel to focus on spiritual maturation. He instructs the Followers of the Way to stringently challenge themselves, speak their truth boldly, yet maintain- inner equanimity and avoid self-righteousness. Faced with opposition on all sides, the course Jesus taught in Luke’s gospel was for the Christus believers to “be” at peace, rather than taking up arms or trying to effect change through anger. This gospel is filled with instructions about growing into the capacity for mature relationships and compassion and generosity without boundaries.”

“The Gospel thus became a “how to” manual designed to be distributed among these burgeoning communities across the Mediterranean world.”