Theme – God’s call challenges us to obedience, compassion and action for justice

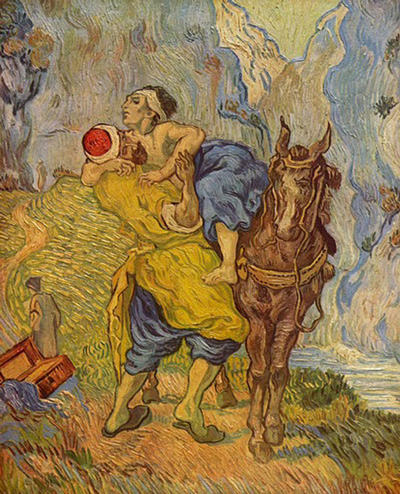

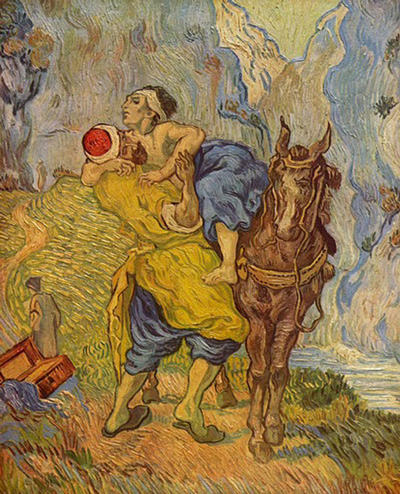

“The Good Samaritan” – Van Gogh (1890)

The lectionary readings are here or individually:

First Reading – Deuteronomy 30:9-14

Psalm – Psalm 25:1-9

Epistle – Colossians 1:1-14

Gospel – Luke 10:25-37

Today’s readings focus on God’s call challenging us to obedience, compassion and action for justice. In Deuteronomy (Track 2), Moses assures the people that God’s call to obedience is not too difficult nor is it hidden. Paul writes that Christ, the image of the invisible God, is our Creator, Sustainer and Reconciler. Jesus answers a lawyer’s question by telling the story of the Good Samaritan.

Read more…

What we say about ourselves is not nearly as important as how we live out what we say—how we live out our lives with Christ. We are called by God throughout scripture and tradition to care for the poor, the outcast, the oppressed, and the marginalized—but throughout our history and scripture, we have found ways to make excuses. We have put ourselves before others and have justified our way of life, while others around us and in the world continue to suffer. We cannot remain ignorant of the struggles of others. Eventually, justice catches up to us

Moses warned the people in the wilderness, and they did not listen. Jesus questions the lawyer who wants the right answer to be given, who wants to speak aloud the truth, and helps him to realize that it is about a love that shows mercy, a way of living towards others. How are we living out our faith? Are we just saying what we believe in? Is it more important to have the right statements of faith, or is it more important to do what Jesus has called us to do and live out our faith?

How often have we passed by persons in need or deferred social involvement to keep our own schedule ? We are not bad persons either; we simply place our broad spectrum vocational callings ahead of the concreteness of God’s call in the present moment.

Our challenge is to grow in stature, so that we can creatively and lovingly balance our personal and institutional responsibilities, including our self-care and care for families and congregations, with the unsettling challenges to go beyond our immediate responsibilities so that we may become God’s partners in healing the world. Jewish mystics remind us that to save one soul is to save the world. From a God’s eye view, this means to care for our loved ones and ourselves as well as those who are loved by God and beyond the walls of our communities. This will lead to agitation but our agitation will find completeness and comfort in feelings of wholeness which emerge when we join our well-being with the well-being of our most vulnerable local and global companions.

II. Summary

The book of Deuteronomy is presented as Moses’ farewell address to the Israelite people gathered at the border of the promised land. The book is a reinterpretation of Mosaic instruction (the Jewish Torah or Law) to deal with the situations of later history. It, or the core of it, was probably “the book of the law” found in 621 BC, which sparked Josiah’s reforms (2 Kings 22–23). It emphasizes the continued relevance of Moses’ teaching to each generation. In its real purpose, Deuteronomy is about starting over, hoping to get it right and keep it going this time, where “it” is national identity expressed through loyalty to God’s law.

Today’s reading comes from Moses’ third address (chaps. 29–30). In this scene, as in others in the book, we see the author leading us away from a classic mythological view of God’s wisdom and direction to a new place wherein God’s teaching is evident and approachable. The people are promised restoration and renewal of the covenant. Following the verses that promise a continuing prosperity, we are led to the feet of the Law, the commandments of God. It is here that Israel will encounter the living one, not in the gifts of God’s blessing

They will enjoy the blessings of obedience (v. 9) if they seek, follow, serve and obey the lord with the total intensity of their whole being (v. 10). God has drawn near and revealed the guidelines that are necessary for living a life pleasing to God. God has already placed these deep within us. Our task is to discover and live them.

What God is asking of them is not too difficult, nor is it far-fetched; but rather, it should become second-nature, because the word is very near them (vs. 14). God delights in us when we are faithful, because we are concerned about the same things God is concerned about. Moses’ hope is that the people remember that the same God who brought them out of Egypt, and gave them manna in the wilderness, and gave them the commandments so that they would know how to follow God’s ways will not forget that God is always with them. Moses’ hope is for the people to remain faithful as God has remained faithful.

Psalm 25:1-10 is a prayer for God’s guidance in this life. This psalm seems to describe the intimacy of God’s wisdom and Law as the Deuteronomist has done in the Old Testament reading this week.

The psalmist seeks God’s protection and help, but also prays for wisdom and insight in how to follow God, seeking forgiveness for where one has made mistakes in the past. The psalmist sings praises for the way God teaches us and gives us direction, and if we are faithful, we will understand God’s faithfulness.

This is an acrostic psalm, each verse beginning with a successive letter of the alphabet – one of nine in the collections of the Psalms.. It is in the form of a personal lament and contains the usual cry for help (vv. 1-3), plea for guidance (vv. 4-5), expression of trust (vv. 6-15) and presentation of the psalmist’s plight (vv. 17-19) in a prayer of vindication (vv. 16-21). The psalm may have been written for general use by any worshiper.

In verses 4-5, the psalmist asks God to teach him truth. He recognizes that his adversaries, both external (vv. 2) and internal (vv. 7), are strong enough to triumph over him. His fear of the lord compels him to acknowledge that God alone can make him into a person of true righteousness (v. 9).

There are images of a journey in these verses, with the central image of the psalmist attempting to walk in the ways of the Lord (see “He guides” (verse 8) and “All the paths” (verse 9). God is pictured here not only as one who shares wisdom, but also as one who forgives when we have forgotten the wisdom.

Today’s reading is the first of a sequence of four Sundays from the letter to the Colossians. The letter to the Colossians addressed tendencies among the Colossian Christians to merge differing beliefs. They had apparently adopted additional teaching, ritual observances and ascetic practices from various sources–Judaism, the pagan mystery cults and speculative theosophy–in order to supplement Christianity and thereby ensure salvation. The letter asserts the entire sufficiency of Christ and of redemption through him.

Today’s reading follows the outline of the beginning of most of Paul’s letters: salutation (1:1-2), thanksgiving (1:3-8) and prayer of intercession (1:9-14). The Colossians are reminded of the gospel they learned from Epaphras (4:12f; Philemon 23). Paul prays that they may be open to God’s will and be strengthened by God to lead moral lives; the connection between knowledge of the gods and ethical behavior was not always made in the pagan religions.

The use of such words as knowledge and wisdom may be a deliberate appropriation of terms used by the mystery religions in order to claim them for Christ. In the Graeco-Roman world at this time there was a general sense of being imprisoned in the world and subjected to evil spirits; thus, many different groups promised deliverance through esoteric knowledge and practices.

What we hear is a message of encouragement, that we no longer live in the power of darkness but in the reign of Christ. The author begins with blessing the Colossians with God’s strength and endurance from God, that they may bear fruit and be pleasing to God and to others. Paul proclaims that it is God who “has delivered us from the dominion of darkness” and it is his Son “in whom we have redemption” through baptism. There is no need to propitiate other powers.

Paul wants them to continue in their knowledge – he mark’s it out: God’s will, spiritual wisdom, understanding. And he prays that there me fruits that come from the faith that they so boldly exhibit. There is a hint of trouble to come, Paul is no Pollyanna, “and may you be prepared to endure everything with patience.” Suddenly at verse 13, the focus shift from the faithful to the faithful Jesus, “in whom we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins.” This is the foundation of the discussion that Paul will have with these people, and which we shall listen in on during the coming Sundays.

Last Sunday the Seventy (or Seventy-Two) were sent out, and when they returned the reported about the things that they had seen. Now we shall meet a character who cannot see. But it is not just the young lawyer who cannot see, the characters in the parable Jesus tells also cannot see.

Today’s reading illustrates the challenge of Christian discipleship in relationship to others. Luke 10:25-37 is the familiar parable of the Good Samaritan. The greatest commandment is listed in all four Gospels in some variation. In Luke’s version, it is not Jesus who answer the questioner with the Greatest commandment, but it is Jesus answering a question with a question—when the lawyer asks “Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

The scholar’s question to Jesus about how to summarize the Jewish Law was one frequently posed to rabbis, who commonly replied with the second part of the answer, taken from Leviticus 19:18b (“you shall love your neighbor as yourself”). The first part is taken from the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4-5 (“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might.”) which was part of the daily morning prayer of the Jews.

Jesus responds with, “What is written in the law?What do you read there?” Jesus is telling the lawyer to look up what is in the law himself. The lawyer picks up on this dance of questions and responds to Jesus – “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself.”

He waits for Jesus’ response, “You have given the right answer; do this and you will live,” the lawyer asks another question, “And who is my neighbor?” His concern about the Law is really about his concern about survival. Even though he knows the answer about God, neighbor, and self, he doesn’t know how to enact it.

Then Jesus tells the parable. By attaching the story of the Good Samaritan, Luke illustrates in a memorable way what the love of a neighbor requires. This also reinforces the Christian application of the Jewish covenant commandments to all persons. In looking for God, we must also see the neighbor, and the neighbor is the last person that we might expect. Usually “the neighbor is the one we would rather avoid.

Jesus asks the question at the end “Which of these three was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?” That is the final question asked, and the lawyer finally has to answer, “The one who showed him mercy.” Love is about showing mercy, and love is about doing justice. This is the way of God, the most important commandment: to love God and to love our neighbor as ourselves, and the way of love is justice and mercy.

Thus a neighbor was a fellow Jew or a resident alien who was under their protection (Leviticus 19:34). The parable turns the question around, from neighbor as object of love to neighbor as one who shows love without defining or delimiting the recipient. Like God (Luke 1:78), like Jesus (Luke 7:13), like the prodigal’s father (Luke 15:20), the despised Samaritan has compassion upon the one in need and acts decisively to rescue the sufferer from the difficult situation.

Today the whole world has become our neighborhood. Scenes of the overwhelming needs of strangers strain our eyes and assault our senses. Crime in our city streets and on the highways has become so common and violent that some of us do not dare be good Samaritans nor teach our children to be friendly to strangers.

Moreover, vast social machinery now exists for taking care of the needy. Many of us give, either voluntarily or under some compulsion to support those agencies and organizations that are the caretakers of social needs. Our social conscience is able to stay alive in this way without too much personal involvement.

So what sense can we in our day make of the one-to-one setting of the parable of the Good Samaritan? The question now seems to be the same one the lawyer asked of Jesus: “Who is my neighbor?” Or, whom are we obliged to help?

Jesus offered no formula to help us make categorical decisions. Implicit in the parable was the only guideline we have—Christ’s loving concern for the individual and willingness to take action to change the situation.

Love is the only energizer and director of our activities that we can trust to guide us. We can know who our neighbor is only when we know who God is. When God’s word is in our hearts and God’s Spirit in our lives, we are able to respond to the needs around us.

Jesus ended the lawyer’s speculative approach to the meaning of life. The parable reversed the lawyer’s question from “Who is worthy of my attention?” to “To whose need must I respond with the love that God shows to me?”

It is by God’s light that we see God’s image in the faces of our brothers and sisters. It is by Christ’s Spirit within us that we extend aid and comfort to them. Real redeeming work, whether for the body or the soul, requires costly, self-sacrificing effort. We pray for grace to bear Christ’s love to all left bludgeoned and abandoned beside the road.