The series will explore words used in the Episcopal Church that may seem arcane to visitors and confusing to old timers. This week’s word is basic – the vestry.

The counties in Colonial Virginia were dominated by the court and the church. Courts held both the executive and judicial arm. They both exacted punishments and also controlled fees as an executive issued licenses, set rates to be charged by inkeepers, set value of tobacco in currency.

The Churches were dominated by the Vestry. There were two vestries. A vestry then meant a meeting of all members of the parish to take care of the church property. “Select vestries” referred to meetings of several of the leading men who had been elected by the members of a particular parish to care for the parish poor between regularly scheduled full vestry meetings. In time “select vestry” became “vestry.”

An Act of Virginia Assembly 1643 created the role of vestries – 12 members of the “most sufficient and selected men to be chosen” with two wardens. The first act of organizing a new parish was to elect the Vestry. This was one of the first democratic experiences in America along with selection of two burgesses for the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg. However vestrymen (no women!) were generally elected for life and became a self-perpetuating group in that when vacancies occurred they appointed men of their own choice to fill the vacancies. The parishoners chose the Vestry unlike the court system where appointments came from Williamsburg.

The Vestry’s powers were greater than its counterpart in England. The best example is the choice of the minister. However, ministers were in short supplies and sometimes vestries had to depend on lay readers. In England nominations were made to the Bishop who appointed the minister. There no bishops in America prior to the Revolution. The vestry was also generally autonomous except when there were major disputers. When disputes interfered with the Vestry, the Governor could summon a General Court in Williams burg which met twice a year to handle disputes.

Vestry powers were much broader than today’s vestry. Vestries enforced the attendance requirement. Church attendance was legally required at least once a month. With large parishes (40 miles long 5-10 wide with a main church and maybe 2 other chapels that could be difficult. However, it is questionable how well that was enforced

Parish vestries had as much autonomy as courts and had equal power to tax. The Court prepared the list of tithables (number of people to assess taxes) by delegating justices to cover every precinct.

In many years the Vestry met only once a year (late September to end of the year) to determine the levy or tax on parishioners to take care of the needs of the church both religious and civil. This could change when a minister had to be changed or a new church built. For the church, it was the Vestry who decided how much to pay the parish minister who was paid in tobacco and casks to put it in, how much to assess for bread and wine in communion. The vestry provided the priest a glebe of 200 or 300 acres, a house, and perhaps some livestock.

In many years the Vestry met only once a year (late September to end of the year) to determine the levy or tax on parishioners to take care of the needs of the church both religious and civil. This could change when a minister had to be changed or a new church built. For the church, it was the Vestry who decided how much to pay the parish minister who was paid in tobacco and casks to put it in, how much to assess for bread and wine in communion. The vestry provided the priest a glebe of 200 or 300 acres, a house, and perhaps some livestock.

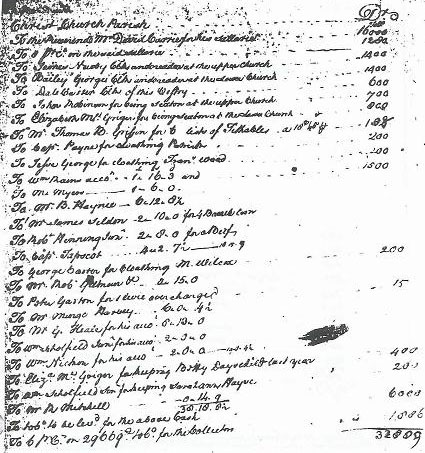

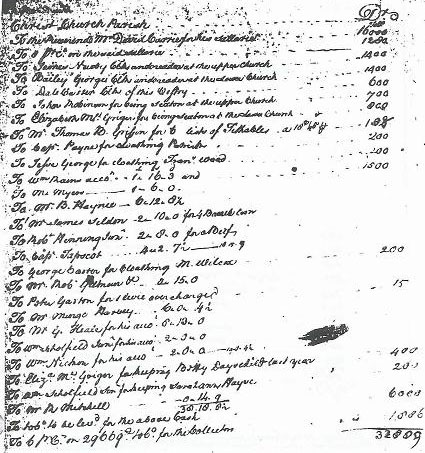

Here is an example. This document is a page from the Vestry Book of Christ Church Parish, 1739-1786. The first line noted the 16,000 pounds of tobacco the Reverend David Currie received annually by law for his services to the parish. Immediately below that was an 8% allowance (4% from each of the two churches in the parish, Christ Church and St. Mary’s White Chapel) given Currie for cask, or packing the tobacco, as well as for loss in the crop from what the Assembly called “shrinkage of the tobacco.”

Vestry duties also consisted of erecting and maintaining the church buildings and chapels. They engaged and appointed church wardens, parish clerks, sextons, and other church officials and of course the minister. Women only served as sextons and were employed as caregivers. Note in the document above, these officials were paid in tobacco – two payments of 1,400 lbs. tobacco each to James Newby and Bailey George, who served as clerks of St. Mary’s White Chapel and Christ Church, respectively.

The levy also had to cover the Vestry’s civil duties due to the role of the church. The church was the source of welfare. With a dispersed and growing population this was a sizable part of the levy. Funds expended on the parish poor often accounted for more than 25 to 30 percent of a parish’s budget The levy was used to reimburse parishioners for burials, doctor fees, costs for nursing the sick and boarding those who needed it. Local vestries had the authority to exempt poor people "from all publique charges except the ministers’ & parish duties."

Vestries also appointed individuals to maintain local roads and provide ferry service over Virginia’s many rivers (although the county courts had largely taken over these tasks by the 1730s); to serve as "tobacco viewers," who ensured that the colonists were not planting too much tobacco; and to serve as churchwardens, who presented moral offenders to the county courts. Parish vestries took special care to relieve parishioners of the expenses associated with raising bastard children, especially those of indentured servants; they held the power to sell female servants to pay for the upkeep of their illegitimate offspring or to force the fathers to put up a bond to cover the expenses of caring for the child.

Vestries were also charged with processioning or "going round … the bounds of every person’s land" in the parish every four years and renewing the landmarks that separated one person’s property from another’s. Lands processioned three times without complaint gained legal status as the formal boundaries of an individual’s property.

Virginia vestries assumed responsibility for many of these duties until the Church of England was disestablished in 1784, existing vestries dissolved, and the counties then became responsible for the church’s civil functions. For example the counties would appoint as overseers of the poor elected to exercise civil powers of the former vestries, especially caring for the poor and for bastard children. The church’s powers became confined to the business of the church as it is today.

In many years the Vestry met only once a year (late September to end of the year) to determine the levy or tax on parishioners to take care of the needs of the church both religious and civil. This could change when a minister had to be changed or a new church built. For the church, it was the Vestry who decided how much to pay the parish minister who was paid in tobacco and casks to put it in, how much to assess for bread and wine in communion. The vestry provided the priest a glebe of 200 or 300 acres, a house, and perhaps some livestock.

In many years the Vestry met only once a year (late September to end of the year) to determine the levy or tax on parishioners to take care of the needs of the church both religious and civil. This could change when a minister had to be changed or a new church built. For the church, it was the Vestry who decided how much to pay the parish minister who was paid in tobacco and casks to put it in, how much to assess for bread and wine in communion. The vestry provided the priest a glebe of 200 or 300 acres, a house, and perhaps some livestock.