I. Theme – The role of the sabbath

The lectionary readings are here or individually:

Old Testament – Deuteronomy 5:12-15

Psalm – Psalm 81:1-10

Epistle –2 Corinthians 4:5-12

Gospel – Mark 2:23-3:6

II. Summary

Three eco-theological themes are readily identifiable this week:

1) Sabbath rest is commanded not only for humans but also for animals, and even for the earth (see also Leviticus 25:1-7);

2) Blessing and salvation are cast in the imagery of an abundance of harvest and good food in the Psalm; and

3) God is pleased to place the glory of Christ in “earthen vessels.”

The word “Sabbath” comes from the Hebrew verb “sabat,” meaning “to rest.” God gave His people a day of rest – in part for a needed day off from their labors, in part so they would have time to worship Him. God knows what we need: Rest for our bodies and spiritual fuel to keep us going the rest of the week.

We have both parts to us: St. Paul compares our bodies to “clay jars” that, incongruously, contain “this extraordinary power (that) belongs to God and does not come from us.” (2 Corinthians 4:7) So God gives the command to observe a weekly Sabbath – a day of physical rest and spiritual renewal – because we need it!!

Then Jesus said to them, “The Sabbath was made for humankind, and not humankind for the Sabbath.” – Mark 2:27

But people being what they are, over the centuries, God’s faithful folk created a very rigid structure with a lot of rules around Sabbath rest. Well, how can you follow God’s commandment if you don’t know what the rules are, right? The Pharisees’ religion had deteriorated into rules, regulations and rituals..

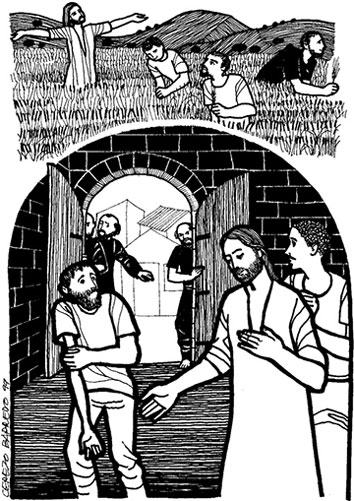

So then Jesus comes along and shakes everything up, curing a man with a withered hand, on a Sabbath, right there in the synagogue!! The good, upright, God-fearing religious authorities were aghast – because curing is, well, work. Jesus knew just what they were thinking, so he challenges them: “Do our rules allow us to do good for someone who needs help on the Sabbath? To save a life, perhaps?” And when the religious authorities can’t answer him, Jesus “was grieved at their hardness of heart.”

Jesus’ operating principle is that the Sabbath ( and the law and the rituals of holiness) was created for humanity, and not the other way around. ’

To make His point still further, Jesus goes into the synagogue and brings a man with a withered arm into the middle of the gathering. Then, He asks the simple question – is it against the law to do good on the Sabbath – or to save a life? Needless to say, His critics have no answer. Jesus has an answer – he heals the man. Mark’s description of healings were important – they were signs that the Kingdom of God was at hand.

II. Summary

Old Testament -Deuteronomy 5:12-15

Julián Andrés González Holguín

In the context of the Israelites’ journey to the promised land, we hear Moses’ words to the people. This setting marks a crucial moment, emphasizing the theological importance of Moses’ guidance. Being in Moab’s plains represents the fulfillment of divine promises of redemption since the people left Egypt. The command to honor the Sabbath reminds them of their liberation experience, urging them to maintain a just relationship with each other and God.

The essence of this passage extends beyond a mere reiteration of existing laws; it emphasizes the significance of the day of rest to acknowledge and highlight God’s redemptive activity. Moses’ words underscore the Lord’s salvific events. God is leading the people out of slavery. They are ready to enter the land of redemption and new beginnings. As the people approach the land, their fidelity to God becomes pivotal, with the Sabbath symbolizing their commitment to a holier existence.

Observing the Sabbath day and keeping it holy underlines the new challenge that the people will face in Canaan. The practice of the day of rest anchors their faithfulness to God as the primary criterion to determine the integral health of the people. This day is a holy day to the Lord, and the community should maintain it as holy by not working. Entering the promised land signifies a tangible realization of their relationship with one another.

The continuous use of the pronoun “you” underscores the text’s emphasis on salvation and redemption. It goes beyond the limits of historical Israel to touch on the lives of its readers and hearers. The text stresses the theological urgency to remember the Lord, especially during the day of rest. Deuteronomy grounds Sabbath observance in the liberation from Egypt, emphasizing equality among all individuals. By subtly altering the command’s language, Deuteronomy highlights its social justice aspects, advocating for the marginalized and breaking oppressive ideologies.

The precept of the Sabbath is established for moral reasons. The liberation from Egypt, not the motif of creation (Exodus 20:11), justifies its observance. In this claim, all people are equal, no matter their social status. Therefore, in the context of Deuteronomy, the commandment of the Sabbath breaks with all “Egypts,” that is, with all oppressive ideologies that regulate job markets in which the many work and the few rest.

Psalm – Psalm 81:1-10

Psalm 81 does not begin with a crisis but with a covenant memory, the memory of God’s faithfulness and a jubilant call to worship (verses 1–5).1

And then, intruding into the middle of the fanfare of praise, the rude word of the prophet, speaking a jarring, discordant truth (verses 6–10), and God’s promise of faithfulness to those who call out to the God of salvation (verses 11–16).

Psalm 81 sits somewhere near the middle of Book III (Psalms 73–89) of the book of Psalms. Historical events—namely, the Babylonian deportation and the destruction of the temple—form a backdrop for these prayers. However, as a rule, the Psalter does not occupy itself with specific historic events but instead with the experience of those events.

According to Patrick D. Miller, the psalmist’s circumstantial ambiguity prevents us from “peering behind” the text, but it also invites us to adapt the text to our own historical situation.2 As such, the cry of the psalmist is the cry of us all.

What sort of cry do we hear from Psalm 81? And could it be the cry for us all, even though we often ignore it? Perhaps it is a call to respond to the cries for justice and compassion in our own age, but especially, given its introduction, in our own houses of worship. This psalm is not addressed to those who are indifferent to God’s justice but to those who sing God’s praise.

And yet, apparently, this congregation does not hear or refuses to hear God’s voice.

According to J. Clinton McCann Jr., Books I–III call out for a response from God’s people.3 Psalm 81 confirms this yearning: “I hear a voice I had not known” (verse 5c); “if you would but listen to me” (verse 8b); “my people did not listen to my voice” (verse 11); “O that my people would listen to me” (verse 13). Psalm 90 begins to answer the cry for response heard in Book III: “Lord, you have been our dwelling place in all generations” (verse 1).

Collectively, the psalmist gives us a worldview in which the whole creation sings God’s praise. Even so, this worldview exists within a context of opposition and suffering. McCann notes that in addition to the psalmist’s self-description as the righteous or the upright, the psalmist self-describes as the poor, the needy, the helpless, and the afflicted: “Not surprisingly … the dominant voice in the psalter is that of prayer.”4

Epistle – 2 Corinthians 4:5-12

Even though it is part of Paul’s long “apology” — or personal defense — for his apostolic ministry against some detractors (in 2 Corinthians 2:14-6:10), it applies to the rest of us since Paul’s basis for defending himself is rooted in “God’s promises,” which are always for everyone (2 Corinthians 1:20; 7:1). What it depicts, with vivid imagery, is a brief phenomenology (a study of a phenomenon) of what being united with the death and life of Jesus the Messiah means for how we experience ourselves and others around us.

Proclaiming the Messiah as Lord and ourselves as your slaves

The passage begins with what could be described as its thesis statement. In the Messiah, what we announce or commend when we present ourselves to others is not our personal or collective egos — our achievements, what makes us special or important, or even the disclosure of some idiosyncratic personal or communal truth (regardless of how authentic it might be). Rather, what we announce is that the Messiah is Lord (the Greek kurios translates the Hebrew YHWH) and that announcement — if sincere — binds us to being slaves of others for Jesus’ sake (2 Corinthians 4:5; see also Mark 8:27-9:1).

Where does this announcement come from, if it does not come from ourselves? Its source lies in God’s speaking creation into being: “Let light shine out of darkness” (see also Genesis 1:3). This “light” reverberates in the coming of a just and merciful Messiah (Isaiah 9:2) and in the righteous who conduct their affairs with justice and distribute their wealth freely to the poor (Psalm 112:4). And it shines in our hearts as well, giving us knowledge of the glory of God in “the face” — the personal presence — of Jesus the Messiah in our lives.

Treasure in clay jars

But we have this “treasure” only in “clay jars” — cheap and fragile earthenware. A metaphor for the vulnerability of our mortal existence, earthenware vessels were also used in the priestly service of temple sacrifice. They could easily be broken or contaminated (see Leviticus).

Why link this treasure with such inexpensive and easily broken vessels? So that it can be clear that this excess — this “hyperbole” — of power comes from God and not from us.

How is this “treasure” actually experienced in the “clay jars” of our vulnerable human lives? Paul portrays how “we are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed” (2 Corinthians 4:8-9). Drawing on language found in the psalms, prophets, and wisdom literature (as well as probably ancient depictions of a sage’s hardships), Paul could also be appropriating traditions about Jesus’ life that would later influence the Gospels. Not only were Jesus and his disciples “persecuted,” but Jesus cries out at his crucifixion, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34; see also Psalm 22:1).

Paul does not depict these extreme hardships in order to highlight his own strength amid adversity. Indeed, he will later parody such displays of prowess (see chapter 11). And he does not present them as an ideal of suffering to follow. Instead, his point is to stress that God’s “shining” through us occurs precisely as we — like the Messiah and the righteous of old — rely solely on God’s promises of justice and mercy in spite of what may happen to us.

Dying and living in Jesus

So “who” do we become as a result of all this? What marks our inexpressible core as individuals? And “what” now defines our identities over time? What identifies us as selves, in spite of what happens to us?

Paul’s response is stark. “Who” we become is now defined solely by carrying Jesus’ death around in our bodies. Only in this way can Jesus’ life be manifest (phaneroo) in those bodies. And “what” defines our identity over time is nothing other than being continually given up to death for Jesus’ sake and the reign of God he embodied. Only in this way is Jesus’ life manifest amid the exigencies of our finite flesh (2 Corinthians 4:10-11).

In other words, we no longer live to preserve our “identities,” whether they take an individual or collective form. Dying in Jesus, we now live solely for the one who died for all so that all might live. This now is what defines our inexpressible core as individuals. This now is what identifies us as selves, in spite of what happens to us. As Paul succinctly put it, “death in me, life for you” (2 Corinthians 4:12).

Of course, ancient and contemporary (so-called) “ministers of righteousness” and “apostles of the Messiah” have often manipulated the starkness of this language to get others to submit to their own agendas (see 2 Corinthians 10-13). Thus, we need to point out that this dying and living in Jesus is not about submitting to a human will, whether it be that of one’s own or another’s ego, or some collective expression of either. And it is not about conforming to an ideal of suffering at the expense of one’s own or anyone else’s humanity.

Rather, what Paul seems to be getting at is this: As all that distorts and spoils our created goodness dies in Jesus — whether we have created that dysfunction or others have imposed it on us — Jesus’ life is manifest as the flourishing of new creation in our lives. But that flourishing and renewal also entails sharing in the sufferings of Jesus — continually being put to death by all that goes against what this crucified Messiah, the Wisdom of God, embodied. In fact, it is precisely as we share in Jesus’ life and sufferings that the light of God’s glory shines — amid our fragile human existence — in the “face” of this crucified Messiah. This is how death in us becomes life-giving for others.

Gospel – Mark 2:23-3:6

The law governing the Sabbath had its origins in the ten commandments given to Moses but by the time of Jesus had become more and more complex. Rules governing the lighting of fires – precisely what counted as work and what did not – even the distance someone could walk on the Sabbath – all were laid down and carefully observed.

To the Pharisees, picking ears of corn was classed as work and so forbidden on the Sabbath – even if the disciples were hungry and this was all they had to eat. Jesus reminds them of an incident in which David bent the Law in order that he and his men could eat.

He highlights the fact that a law given for the good of God’s people was actually a burden to them. Instead of enjoying their day of rest and spending precious time in worshipping God – they were concerned not to transgress any of the additional rules imposed on the Sabbath.

The Sabbath was given for human creatures – not the other way around.

To make His point still further, Jesus goes into the synagogue and brings a man with a withered arm into the middle of the gathering. Then, He asks the simple question – is it against the law to do good on the Sabbath – or to save a life? Needless to say, His critics have no answer.

Jesus is angry that they are not prepared to reflect on the question – and so offers an answer that they must have suspected was coming: He heals the man.

The answer to the question is, of course, self-evident – and the healing of the man cannot be seen as doing evil on the Sabbath. But the reaction of the critics is not to think again – to reflect on the meaning of the Sabbath. Rather it is to see Jesus as a threat to good order – and to their position.

Even at this early stage of his Gospel, Mark makes clear that such confrontations led to Jesus’ opponents to being the plots which were to lead eventually to His death.