Memorial Day, May 30, 2021(full size gallery)

2024 Sun May 26

Trinity Sunday

Trinity Sunday, the first Sunday after Pentecost, honors the Holy Trinity—the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Although the word “trinity” does not appear in Scripture, it is taught in Matthew 28:18-20 and 2 Corinthians 13:14 (and many other biblical passages). It lasts only one day, which is symbolic of the unity of the Trinity.

Trinity Sunday, the first Sunday after Pentecost, honors the Holy Trinity—the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Although the word “trinity” does not appear in Scripture, it is taught in Matthew 28:18-20 and 2 Corinthians 13:14 (and many other biblical passages). It lasts only one day, which is symbolic of the unity of the Trinity.

Trinity Sunday is one of the few feasts of the Christian Year that celebrates a reality and doctrine rather than an event or person. The Eastern Churches have no tradition of Trinity Sunday, arguing that they celebrate the Trinity every Sunday. The Western Churches did not celebrate it under the 14th century under an edict of John XXII

Since that time Western Christians have observed the Sunday after Pentecost as a time to pause and reflect on the Christian understanding of God

The intention of the creeds was to affirm the following core beliefs:

-the essential unity of God

-the complete humanity and essential divinity of Jesus

-the essential divinity of the Spirit

Understanding of all scriptural doctrine is by faith which comes through the work of the Holy Spirit; therefore, it is appropriate that this mystery is celebrated the first Sunday after the Pentecost, when the outpouring of the Holy Spirit first occurred.

The Trinity is best described in the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, commonly called the Nicene Creed from 325AD.

Essentially the Trinity is the belief that God is one in essence (Greek "ousia"), but distinct in person (Greek "hypostasis"). The Greek word for person means "that which stands on its own," or "individual reality," but does not mean the persons of the Trinity are three human persons. Therefore we believe that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are somehow distinct from one another (not divided though), yet completely united in will and essence.

The Son is said to be eternally begotten of the Father, while the Holy Spirit is said to proceed from the Father through the Son. Each member of the Trinity interpenetrates one another, and each has distinct roles in creation and redemption, which is called the Divine economy. For instance, God the Father created the world through the Son and the Holy Spirit hovered over the waters at creation.

The Importance of Trinity Sunday

Article from Building Faith – “Three Teaching Points of Trinity Sunday”

God is Love Because God is Trinity. “In the First Letter of John, we find one of the most comforting and profound claims about God, “So we have known and believe the love that God has for us. God is Love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.” (I John 4:16). For this to be true, for God to be love, completely and perfectly, God must also be Trinity. For there to be love you need three things; the lover, the beloved, and the love or union shared between the two. Only in the revelation of God as Trinity can we see that God is love.

The Trinity Is To Be Loved, Not Solved. “Look again at our verse from First John, “God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them.” John is not trying to help us solve a puzzle; instead, he wants us to see that the Triune God has created us so that we might share in his love, that we might abide in God and God in us.

The Trinity is the Central Mystery of the Christian Faith and Life “When we are baptized, it is in the Name of God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Our prayer is Trinitarian in shape; for example, the collects in the Book of Common Prayer (BCP pg. 211) are addressed to the Father, through the Son, in unity with the Holy Spirit. Many of the postures we use in worship and prayer are Trinitarian; the sign of the cross, for example, invokes the Name of the Triune God. The whole of our lives as Christians is a participation in the mystery of the Holy Trinity.

Lectionary, Pentecost1 Trinity Sunday, Year B

I. Theme – The Trinity points to the mystery of unity and diversity in God’s experience and in the ongoing creative process

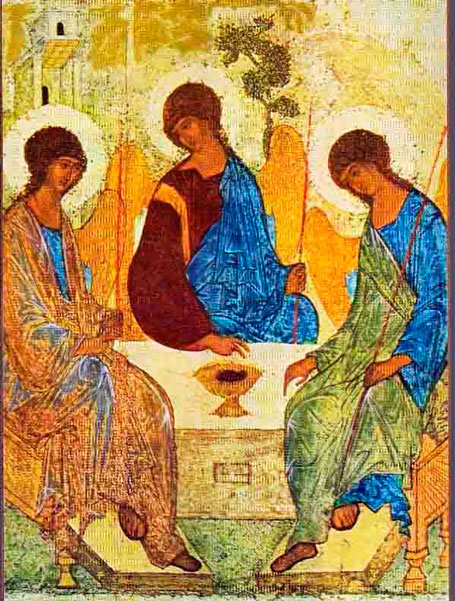

Holy Trinity– Anton Rublev (1430)

The lectionary readings are here or individually:

First Reading – Isaiah 6:1-8

Old Testament – Psalm 29 Page 620, BCP

Epistle –Romans 8:12-17

Gospel – John 3:1-17

Commentary by Rev. Mindi

The Call of Isaiah is dictated in chapter 6 with a glorious vision of God as a king seated on a throne surrounded by his attendants, the six-winged seraphs above the Lord. Even the seraphs seem not worthy of God, covering their feet and their faces, not daring to touch the holy space of heaven, not daring to look upon the face of God. Isaiah feels unworthy to speak in God’s presence, until the coal is pressed to his lips and Isaiah is purified. We are reminded through Isaiah’s vision that God is beyond our understanding, beyond our comprehension, but we do have a way of responding to God: through our answering God’s call, through our saying “yes” to God, to our saying, “Send me!” We may not understand God, but God understands us, and calls us into the world to carry God’s message.

Psalm 29 speaks of God as the Great Creator, whose voice carries the power of creation. God calls forth creation by speaking in Genesis 1 and the creative power of God’s voice is echoed here. It is God’s voice that calls creation out of the void, the deep, the darkness–and it is God’s voice that calls us out of the darkness of the world to witness to the light.

John 3:1-17 is the familiar story of Nicodemus which we read a portion of during Lent. Jesus speaks to Nicodemus about being born of the Spirit, and that God’s love for the whole world is so great that God has sent Jesus. We often read verse 16 without reading verse 17–that God did not send Jesus to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him. Using the Father-Son language, we understand the relationship of Christ to the Creator to be intimate, close, indwelling, along with the Spirit–a hint at the Trinity. While the Trinity is a concept never named in the Bible, we have inferred the triune relationship of God through scriptures such as these, knowing that we can never fully understand God, the Trinity helps us understand how God has been made known to us.

Romans 8:12-17 also infers the triune relationship of God by tying in our relationship with Christ as also being children of God, who have a close relationship with God to where we also can call God Abba (the Aramaic word for Father that Christ used indicates closeness). And we are led by the Spirit of God, who guides us in this world to the way of life.

Reflection and Response

We stand on holy ground. That truth resonates throughout today’s readings, reminding us of the essential sacredness of our experience, throughout all times and seasons.

The sacred character of human life springs from our intimate connection with the triune deity. God’s self-identification to Moses is not that of some distant figure, aloof from human life. Instead, he is the God of people: Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, Jacob and Rachel. If we substitute the names of our own parents or loved ones, we get the message. God is part and parcel of that most close and frustrating human relationship.

To see our ordinary days in this divine light takes a special gift of the Spirit. Elusive as the wind, it inspires and empowers us, enabling us to rise above our mortal limitations and place our lives in the context of the holy. The normal bounds of our thinking can be utterly shattered and expanded, just as Moses’ were when he saw a bush burning, yet not consumed.

The same irony is present as we realize that we are deeply human, yet somehow more than that. Redemption by Jesus implies that although we are doomed to die, we also inherit eternal life. The implications of that fact should brighten the dusty surface of our days.

We older folk become as skeptical as Nicodemus about the possibilities for rebirth. The noted teacher is quite willing to admit that the signs Jesus does mark him as one who lives in the presence of God. Yet the next step Jesus asks him to take is the difficult one: acknowledging that any person can see God’s kingdom as clearly, enter into this reign and be born of the Spirit.

In so doing, Paul says, we become joint heirs with Christ, suffering with him so that we can also share his glory. It is our union with Christ that makes all ground holy: our affections, our work, our suffering and triumphs.

Quietly consider:

If I am an heir of God, how then should I act?

Visual Lectionary Vanderbilt, Trinity Sunday, May 26, 2024

Click here to view in a new window.

Visualizing the Trinity

The Trinity is most commonly seen in Christian art with the Spirit represented by a dove, as specified in the Gospel accounts of the Baptism of Christ; he is nearly always shown with wings outspread. However depictions using three human figures appear occasionally in most periods of art.

The Father and the Son are usually differentiated by age, and later by dress, but this too is not always the case. The usual depiction of the Father as an older man with a white beard may derive from the biblical Ancient of Days, which is often cited in defense of this sometimes controversial representation.

The Son is often shown at the Father’s right hand.[Acts 7:56 ] He may be represented by a symbol—typically the Lamb or a cross—or on a crucifix, so that the Father is the only human figure shown at full size. In early medieval art, the Father may be represented by a hand appearing from a cloud in a blessing gesture, for example in scenes of the Baptism of Christ.

Later, in the West, the Throne of Mercy (or “Throne of Grace”) became a common depiction. In this style, the Father (sometimes seated on a throne) is shown supporting either a crucifix[111] or, later, a slumped crucified Son, similar to the Pietà (this type is distinguished in German as the Not Gottes)[112] in his outstretched arms, while the Dove hovers above or in between them. This subject continued to be popular until the 18th century at least.

By the end of the 15th century, larger representations, other than the Throne of Mercy, became effectively standardised, showing an older figure in plain robes for the Father, Christ with his torso partly bare to display the wounds of his Passion, and the dove above or around them. In earlier representations both Father, especially, and Son often wear elaborate robes and crowns. Sometimes the Father alone wears a crown, or even a papal tiara.

In the 17th century there was also a brief vogue for representing the Trinity as three identical men (example), conceivably influenced by Hospitality of Abraham images. This period coincided with the Spanish ascendancy in Latin America and the Philipines, so examples can be found in older churches in those areas. One odd example represents the Trinity this way in an image of the Coronation of Mary.

Soon, however, this type of Trinity image was condemned and supplanted by one in which the Father is represented as an older person, the Son as a younger one seated at his right and shouldering a large cross, and the Holy Spirit as a dove that hovers above the space between them. In the latter type the Spirit is represented as casting light upon the other two persons (symbolically, making it possible for humans to know them), but in one unusual variant he emanates from both their mouths simultaneously, a reference to the Latin trinitarian theology in which the Spirit “proceeds from the Father and the Son” (a phrase from the Roman Catholic text of the Nicene Creed that reads simply “proceeds from the Father” in the Orthodox and Anglican versions).

Trinity Sunday – the Trinity Knot

Trinity Sunday on our church calendar is the only Sunday in the year devoted to a doctrine of the church.

The Trinity Knot is also known as ‘Triquetra’ which comes from the Latin for ‘three-cornered’. It has been found on Indian heritage sites that are over 5,000 years old. It has also been found on carved stones in Northern Europe dating from the 8th century AD and on early Germanic coins. It developed during Ireland’s Insular Art movement around the 7th century

It’s likely the Trinity knot had religious meaning for pagans and it also bears a resemblance to the Valknut which is a symbol associated with Odin, a revered God in Norse mythology. According to the Celts, the most important things in the world came in threes; three domains (earth, sea and sky), three elements, three stages of life etc. It is also possible that the Triquetra signified the lunar and solar phases. During excavations of various archaeological sites from the Celtic era, a number of Trinity knot symbols have been found alongside solar and lunar symbols.

For Christians, the Trinity knot consists of three corners, some designs also include the circle in the center. The three points of the Trinity knot represent the Holy Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit and the circle eternal life

Exploring Rublev’s famous Trinity Icon

This was written by Bill Gaultiere published by Trinity Episcopal

“Andrei Rublev painted “The Hospitality of Abraham in 1411” for the abbot of the Trinity Monastery in Russia. Rublev portrayed what has become the quintessential icon of the Holy Trinity by depicting the three mysterious strangers who visited Abraham (Genesis 18:1-15).

“In the Genesis account the Lord visits Abraham in the form of three men who are apparently angels representing God. Abraham bows low to the ground before his three visitors and they speak to Abraham in union and are alternatively referred to by the Genesis writer as “they” or “the Lord.” Abraham offers them the hospitality of foot washing, rest under a shade tree, and a meal and they offered him the announcement that God was going to give he and his wife Sarah a son, though Sarah was far past the age of childbearing.

“Rublev was the first to paint only the three angelic figures and to make them of equal size. Rublev depicts the three as One Lord. Each holds a rod in his left hand, symbolizing their equality. Each wears a cloak of blue, the color of divinity. And the face of each is exactly the same, depicting their oneness.

“The Father is like the figure on the left. His divinely blue tunic is cloaked in a color that is light and almost transparent because he is the hidden Creator. With his right he blesses the Son – he is pleased with the sacrifice he will make. His head is the only one that is lifted high and yet his gaze is turned to the other two figures.

“The Son is portrayed in the middle figure. He wears both the blue of divinity and reddish purple of royal priesthood. He is the King who descends to serve as priest to the people he created and to become part of them. With his hand he blesses the cup he is to drink, accepting his readiness to sacrifice himself for humanity. His head is bowed in submission to the Father on the left.

“The Spirit is indicated in the figure on the right. Over his divinely blue tunic he wears a cloak of green, symbolizing life and regeneration. His hand is resting on the table next to the cup, suggesting that he will be with the Son as he carries out his mission. His head is inclined toward the Father and the Son. His gaze is toward the open space at the table.

“Did you notice the beautiful circular movement in the icon of Father, Son, and Spirit? The Son and the Spirit incline their heads toward the Father and he directs his gaze back at them. The Father blesses the Son, the Son accepts the cup of sacrifice, the Spirit comforts the Son in his mission, and the Father shows he is pleased with the Son. Love is initiated by the Father, embodied by the Son, and accomplished through the Spirit.”

From Henro Nouwen, Dutch priest (psychology professor, writer, theologian) writing more than 500 years after this painting, “The more we look at this holy image with the eyes of faith, the more we come to realize that it is painted not as a lovely decoration for a convent church, nor as a helpful explanation of a difficult doctrine, but as a holy place to enter and stay within.”

Nicene Creed – line by line

We say this creed every Sunday in the Eucharist service. It is the central creed or belief of Christianity and goes back to 325AD. On Trinity Sunday it is good to break it down into its essential meaning.

Walls of Nicea

“I believe in one God“

The Greek, Latin and proper English translations begin with “I” believe, because reciting the creed is an individual expression of belief.

“the Father Almighty “

God the Father is the first person, within the Godhead. The Father is the “origin” or “source” of the Trinity. From Him, came somehow the other two. God the Father is often called “God Unbegotten” in early Christian thought.

“Maker of heaven and earth, And of all things visible and invisible: “

Everything that is was created by God. Some early sects, the Gnostics and Marcionites, believed that God the Father created the spirit world, but that an “evil” god (called the demiurge) created the similarly evil material world.