- A house with a furnace is like a car that idles all day. Swap your furnace for a heat pump, which works by extracting heat from one location and transferring it to another (Tax Credit : 30% of the cost paid by the consumer, up to $2,000/year,)

- Swap your gas stove for an electric stove, which will also lower indoor air pollution (rebate amount has not been publicized year)

- Install a programmable thermostat model to turn off the heat/air conditioning when you’re not home.

- Get a home or workplace energy audit to identify where you can make the most energy-saving gains. ( Tax credit – 30% of the cost paid by the consumer, up to $150)

- Consider Solar- This is a significant expense but can vary depending on the company you choose.

30% federal tax credit via Inflation reduction act. State – – A property tax exemption for the increase in home value after going solar.

Solar Renewable Energy Certificates (SRECS), which are financial incentives for generating clean electricity. You gain one SREC for every 1,000 kilowatt-hours generated by your solar panels, and you can sell the credits to local electricity providers and other organizations that are subject to renewable energy mandates. As of 2023, each SREC can be sold for around $45 to $70.

Solar alternative – Even if you can’t install solar panels, you can still be a part of the clean-energy economy. Check out – Old Dominion Electric Cooperative (ODEC) odec.com. ODEC has entered several long-term purchase power agreements for energy generated by wind, solar, and landfill gas resources. .

Your home – other

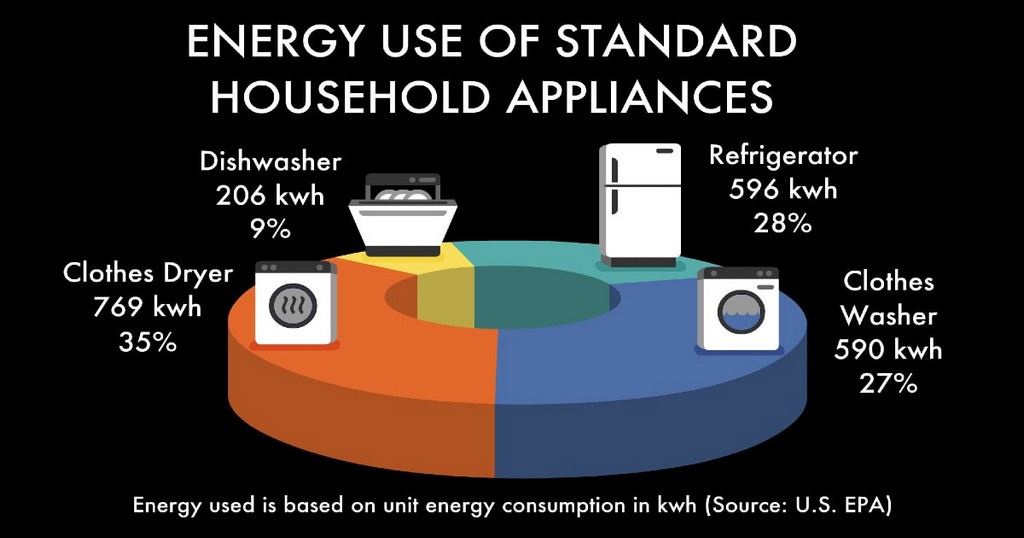

- Unplug computers, TVs and other electronics when you’re not using them

- Turn off lights you’re not using and when you leave the room. Change to energy-efficient LED bulbs

- Wash clothes in cold water. Hang-dry your clothes when you can

- Draft proof.

Drafts waste five to 30 per cent of energy. Those from basements and roofs cool the most. Seal doors, windows and chimneys in those areas first. Try testing with incense. Where the smoke wavers, a draft is blowing in.To seal leaks, make or buy a “door snake” and caulk and weatherstrip doors and windows. Look for non-toxic, eco-friendly caulks. You can also add small insulating covers underneath electric outlet wall plates on outside walls or beside cold basements and crawl spaces. - Insulate windows.

Hang heavy curtains to keep the cold out and the cozy in. A cheaper solution: insulation film, available at most hardware stores. This plastic shrink film is easy to apply and keeps in much of the heat that would otherwise escape. - Reverse ceiling fans.

Many ceiling fans have a reverse mode. When they turn clockwise, they push down warm air that pools near the ceiling and circulates it through the room. - Change furnace filters.

Dirty filters restrict airflow and increase your furnace’s energy demand by making it work harder. Replace filters at least every three months during the heating season.Better indoor air quality is a nice side benefit of this energy-saving tip. Consider switching to a washable filter, which reduces waste and is more effective. - Check your thermostat.

Every degree you turn it down can save between 1.5 and five per cent of your heating bill. A programmable thermostat will help you get efficient and consistent.Turn down the thermostat when you’re sleeping or out. It’s is the most efficient way to reduce your heating bill — and your eco-footprint.

Transportation

Carpooling

- Combine errands to make fewer trips. Remove excess weight from your car. Use cruise control.

Consider electric or hybrid or low carbon vehicle for your next car

Speeding and unnecessary acceleration reduce mileage by up to 33%, waste gas and money, and increase your carbon footprint.

- Properly inflated tires improve your gas mileage by up to 3%. It also helps to use the correct grade of motor oil, and to keep your engine tuned

Fly less and take alternate transportation

on the bottom right of the PowerPoint window to enlarge

on the bottom right of the PowerPoint window to enlarge