“This weekend we honor workers. Those whose efforts produce fruit that benefit us all. It seems like a good time also to define labor for those who follow Jesus. First, it’s prioritizing “divine things” over “human things” according to Jesus. That means risk taking obedience to God over obsession with personal convenience and safety. Then there is the labor of self-denial for the sake of the common good and common wealth. Finally, we are to “take up our cross.” That’s our: wounds, struggles, longings and joys by positioning them in the wake Jesus created by his soul-saving labor. Jesus says, this work will secure your soul and keep you alive.” – Bishop Rob Wright, Diocese of Atlanta

Commentary

Lectionary Commentary August 31, Pentecost 12

I. Theme – Our lives should exhibit humility and love

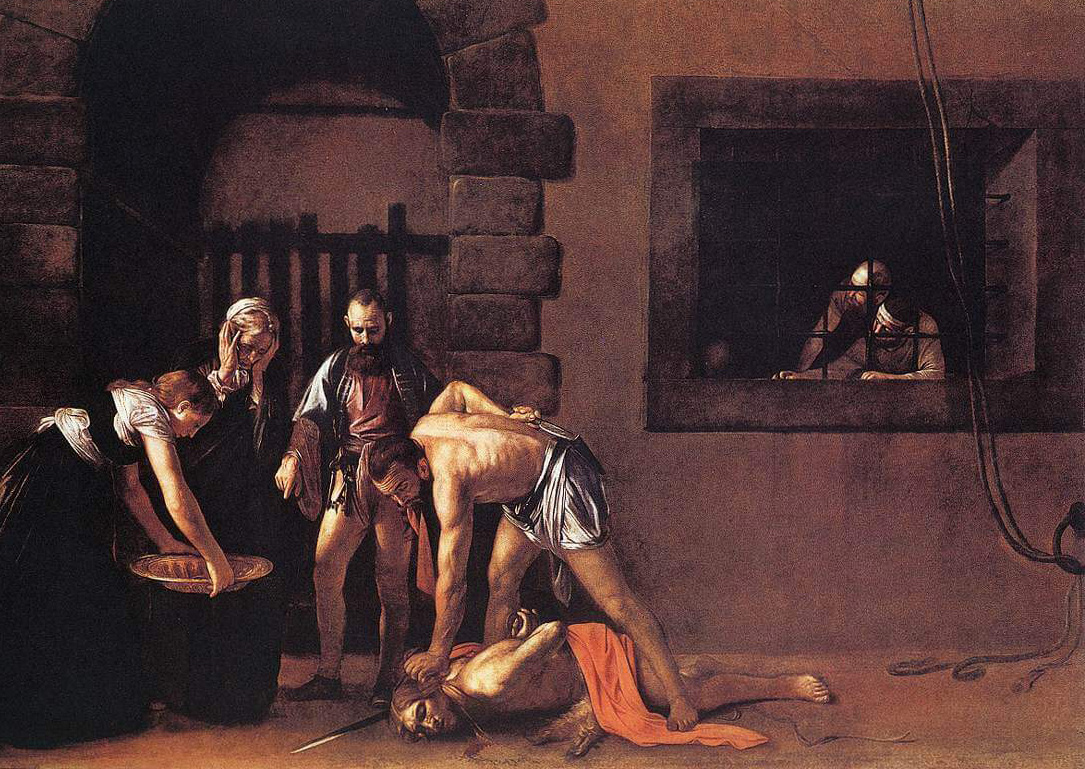

Feast of Simon the Pharisee” – Peter Paul Rubens (1618-1620)

The lectionary readings are here or individually:

First Reading – Sirach 10:12-18 or Proverbs 25:6-7

Psalm – Psalm 112

Epistle – Hebrews 13:1-8, 15-16

Gospel – Luke 14:1, 7-14

Today’s readings remind us that our Christian way of life is characterized by humility and love. The wisdom teacher Sirach warns his readers to avoid arrogance, violence and pride. The author of Proverbs counsels about having a humble attitude and being content with one’s own social status. The author of Hebrews urges readers to make Christian love a practical reality in their lives.

At a banquet, Jesus teaches the meaning of true humility.Jesus’ teachings on humility challenge us, and cause us to go deeper—it is not enough to humble ourselves in the presence of others, but to actively reach out and invite those who would not be invited to join in. We are called to live out our witness, especially when it is hard and goes against the grain of the world. How does the invitation of Jesus challenge us at the table as we celebrate?

Some of us may know the honor of sitting at the head table at some social or business function. Because recognition of our importance is a coveted honor, the scene in Jesus’ parable of the wedding feast is familiar to us. Who has not looked for his or her place card near the host and been disappointed to find other names at the seats of honor?

The twinge we feel when we do not make the head table at important meetings reveals the fact that we still have a trace of the old nature in us. We want to look rich before people; we forget how rich Christ has made us before God.

Our earthly status is always insecure; it waxes and wanes, and the retirement party inevitably comes. Newcomers take our place, and we are expected to go fishing–or at least stay out of the way of our successors. Not so in God’s service. Once a saint, always a saint here. We are never retired from work in the kingdom. Our future is to be more glorious than is our present in God’s service.

God continues to give freely to us who are poor in what matters most. Our attempts to emulate God’s generosity and hospitality are received and honored when done in the spirit of humility that befits God’s image in us. Then, like God, we too can enjoy the company of those who can never repay us.

The Gospel – Luke 14:1, 7-14 – Pentecost 12. The Way Up With God Is Down

"Feast of Simon the Phrarisee" – Peter Paul Rubens (1618-1620)

I love David Lose’s comment on this passage -“If there was ever a gospel reading that invited a polite yawn, this might be it. I mean, goodness, but Jesus comes off in this scene as a sort of a progressive Miss Manners.” He later backs off of it.

Jesus is on his way to Jerusalem. And so this, and all reported encounters with religious authorities, are going to clarify and sharpen the division between Jesus’ vision of right now, right here, being the time and the place for the realization of God’s Kingdom, and the authorities’ anxiety to keep social peace as defined and enforced by the Roman occupiers.

He is invited to dinner by the big cheese – “house of a leader of the Pharisees”. Jesus does not seem to be invited for the hospitality of it, but for the hostility of it. The setting seems hostile. Sabbath controversy stories in chapters 6 and 13 had both ended with pharisees on the defensive (6:7; 13:17). Chapter 11 had ended with the pharisees "lying in wait for him, to catch him in something he might say." (11:54).

Thus Jesus is not being watched closely to see what they might learn from him. He is being watched closely to assess just how much of a threat he really might be. He is being tested outside of the admiring crowds. Jesus is watching them very closely in order to make observations about human conduct. He wanted to contrast their kingdom of ritual with the kingdom of God emphasizing mercy and radical inclusion.

The word pharisee can mean "to separate". The Pharisees were a group of people who separated themselves from the riffraff of society. They sought to live holy and pure lives, keeping all of the written and oral Jewish laws. Often in the gospels, Pharisees are pictured as being holier-than-thou types, the religious elite. They felt that they had earned the right to sit at the table with God. They criticize Jesus because he doesn’t separate himself from the "sinners and tax collectors."

The Gospel is sandwiched between two other situations. Just before the Gospel Jesus heals a man with dropsy and defended that Sabbath healing. He may have been the bait

There are two main scenes here with advice:

1. Going to banquet sit at the lowest place so you can move up rather than forced down

In Israel, the meal table played a very important role, not only in the family, but in society as well. When an Israelite provided a meal for a guest, even a stranger, it assured him not only of the host’s hospitality, but of his protection Also in Israel (as elsewhere), the meal table was closely tied to one’s social standing. “Pecking order” was reflected in the position one held at the table

Jesus knows that most people would want to take the place of honor. What is interesting is that those who put themselves forward to take the highest or most dignified place might be removed not to the second place but to the lowest place.

And, Jesus takes pains to show that this "demotion" is really an experience of humiliation. Rather than seeking to put ourselves forward, we are to wait until we are invited up to the honored position.

When the guests jockeyed for position at the table, Jesus spoke to this evil as well (vv. 7-11). While they believed that “getting ahead” socially required self-assertion and status-seeking, Jesus told them that the way to get ahead was to take the place of less honor and status. Status was gained by giving it up. One is exalted by humbling himself, Jesus said.

Note that Jesus is not criticizing the system but how people operate within it.

His exhortation is to pursue humility, a concept with significant status connotations. Humility was very rarely considered a virtue in Greco-Roman moral discourse.

Humility doesn’t mean being passive. Letting others walk all over us Jesus shows by his life that being humble didn’t mean being passive, but, when necessary, it meant taking out the whip and driving the self-centered bullies out of the temple.

There is a balance between being humble without self-degradation or shame of letting others "walk all over" us vs. deliberately putting ourselves above others through self-exaltation or arrogance.

Exaltation depends too if you are doing the exalting or God raising up and exaltation belong to God; recognition of one’s lowliness is the proper stance for human beings. The act of humbling oneself is not something for its own sake, but for the sake either of God or of Christ .Jesus advises a strategy of deliberately and consciously living beneath one’s presumed status in order to receive even greater honoring later.

Some scholars speculate that this teaching would particularly apply to Luke and his first readers as they were higher status Gentiles, and the mixed-status Christian communities would require them to live beneath their comfort zone. God would later recognize and honor their accepting of lower social standing.

Here is a paradox indeed. The way up is down. To try to “work up” is to risk being “put down.” Those who wish to be honored must be humble and seek the lowly place. Those who strive to attain the place of honor will be humiliated

2. If you are the host, don’t invite who can in turn invite you and be repaid but invite “ the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind” and be repaid by God

Shift in emphasis here. Now Jesus is not working within the system but challenging it.

The host had apparently invited all the prominent people to his table on this occasion.

Jesus assumes that you are putting on the feast, rather than attending a marriage banquet, and that you have to put together your guest list. Guest lists are put together based on a philosophy or on some kind of principle. Two popular ways to do it are because you "owe" someone who has invited you to their event or you want to "get in good" with some people and so you extend an invitation to them

First century middle-eastern dinner parties were political, social, and class affairs. One would invite those considered one’s social equals or superiors. Accepting an invitation to a such a dinner carried with it the expectation that the one invited would return the favor.

Obviously, in the unlikely event they would get an invite, poor people would not accept since they would not be able to repay.

The central principle of this advice is that we are to give things to people without expecting any kind of return.

Jesus told him that while men might seem to get more in return from inviting their friends, family, and prominent people to a meal, in heaven’s currency men were rewarded by God when they invited those who could not give anything in return—the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind.

Jesus calls for “kingdom behavior”: inviting those with neither property nor place in society. God is our ultimate host, and we, as hosts are really behaving as guests, making no claims, setting no conditions, expecting no return.

We are to do good to people regardless of their ability to repay. In fact, we might delight even more in extending ourselves to people if they can’t repay because, in this case, we will have a reward at the "resurrection of the righteous."

Notice here that the listing: the poor, the crippled, the lame and the blind – reflect those listed in Jesus’ initial declaration for his ministry way back in Luke 4:18. Your "blessing" is the total removal of social rank in the reign of God. In God’s eyes, this is justice, and you will be rewarded at the "resurrection of the just."

Helping the needy is more than just sending money, but getting involved with the people — perhaps sitting down together with them as equals at a supper table.

What the "helpers" frequently discover is that Christ serves them through the needy. Jesus says we need to start inviting new people to dinner and it may challenge our comfort zones.

We are disciples on the road – disciple on the road with Jesus is to share with those who have nothing and who can give nothing in return.

Back to David Lose on inviting the “the poor, the crippled, the lame and the blind”:

“And while that sounds at first blush like it ought to be good news, it throws us into radical dependence on God’s grace and God’s grace alone. We can’t stand, that is, on our accomplishments, or our wealth, or positive attributes, or good looks, or strengths, or IQ, or our movement up or down the reigning pecking order. There is, suddenly, nothing we can do to establish ourselves before God and the world except rely upon God’s desire to be in relationship with us and with all people. Which means that we have no claim on God; rather, we have been claimed by God and invited to love others as we’ve been loved.

“As we see in today’s reading, precisely because we have been invited into relationship by God — because, that is, God has conferred upon us freely a dignity and worth we could never secure for ourselves — we are free to do the same for others. We are free to put them before ourselves, to lead them to seats of honor, to invite them to be our dinner guests, not because of what they can do for us, but because of what has already been done for all of us.

“It’s a new humanity Jesus is establishing, a new humanity that has no place for our insecurities and craving for order. Which is why it’s frightening and why those invested in the pecking order — which, of course, includes all of us — will put him to death.&qu

The Cultural background of the Gospel reading

In this passage (Luke 14:1, 7-14), Jesus’ teaching is set in the context of a Sabbath meal at the home of a prominent Pharisee. The key themes are criticism of the Pharisees for their pride and hypocrisy and affirmation of God’s love for the lowly and outcast. Humility and love should characterize the people of the kingdom.

Cultural & Historical Background

- Banquets in the Ancient World

- In the Greco-Roman and Jewish world, banquets were more than meals—they were social events that displayed honor, status, and hierarchy. You normally would eat with only those in your social class

- Honor and shame were pivotal values of the ancient Mediterranean world. A family’s honor in the community determined whom they could marry, what functions they could attend, where they could live, and with whom they could do business

- Seating mattered: One’s placed at the table was determined by social status. The closer you sat to the host, the more important you were considered. The “best seats” (Luke 14:7) were typically nearest the host or in the center of attention. The public shame of moving from the first seat to the last in front of one’s colleagues would be a humiliation almost worse than death

- Reciprocity system: Invitations were strategic. You invited people who could invite you back or enhance your reputation. Banquets often reinforced the social pecking order.

- Sabbath Meals

- The terms in 14:12 refer to the two daily meals: the ariston, a late morning meal, and the deipnon, a late afternoon meal The “banquet” (doch) in 14:13 is a more formal dinner party or reception.

- A Sabbath meal (Shabbat meal) was an honored tradition in Jewish culture. After synagogue, a household would host a festive meal.It was a time of joy, but also of status display—especially in wealthy or influential families. Hosting a Sabbath meal was a mark of piety and prestige.

- But Jesus says that those who seek self-glorification will ultimately find themselves humbled, while those who put others first will be exalted. The highest calling of a Christian is to look out for others first, encouraging them to be all that God would have them to be.

- Honor and Shame Culture

- Honor/shame was the central value system in Jesus’ world.

- To seek the place of honor (Luke 14:7) was expected, because honor was public recognition of worth. Losing face (being told to move down the table, v.9) was a public shame.

- Jesus flips the script: the way to true honor in God’s kingdom is humility (v.11). Do not take the place of honor (14:8). Jesus’ words here are a commentary on Proverbs 25:6–7: “Do not exalt yourself in the king’s presence, and do not claim a place among great men; it is better for him to say to you, ‘Come up here,’ than for him to humiliate you before a nobleman.”

- He who humbles himself will be exalted (14:11). Jesus encourages his followers not to seek honor but to serve others in humility. While similar proverbial wisdom appears in Sirach 3:18 (“The greater you are, the more you must humble yourself; so you will find favor in the sight of the Lord”).

- Jesus’ words echo Ezekiel, who predicted that in the wake of God’s judgment, “The lowly will be exalted and the exalted will be brought low” (Ezek. 21:26

- Who to Invite?

- Social expectation: You invited friends, relatives, rich neighbors—those who could “pay you back” (v.12). This built networks of obligation and prestige.

- Jesus challenges this: Invite “the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind” (v.13)—those excluded from power, unable to repay, and often seen as cursed or unclean. It was uncommon to eat with the poor. Such fraternization could risk one’s social standing with friends and colleagues

- This reflected the upside-down kingdom of God: grace, not reciprocity, defines relationships.

- Jewish and Biblical Roots

- Humility was a virtue in Hebrew wisdom tradition (cf. Proverbs 25:6–7, which Jesus echoes).

- Hospitality to the poor is deeply rooted in the Law and Prophets (Deut. 14:28–29; Isa. 58:6–7). Jesus restores this neglected teaching.

- The vision anticipates the eschatological banquet—God’s great feast at the end of the age (Isa. 25:6–9; Luke 14:15–24). Those society excluded will be honored guests in God’s kingdom.

Beheading of John the Baptist, Aug. 29

Matthew has told us of the beheading of John the Baptist – killed because John denounced Herod Antipas’ marriage to his brother Philip’s wife when Philip was still alive (a violation of Jewish law). Jesus is reeling over this.

His reaction is to withdraw privately to a desert-like, remote place. So Jesus withdraws to be alone with his thoughts and his sorrows – in a “deserted place” to regroup, to recharge. But it doesn’t work, of course. The eager crowds are on him – there is no rest for the weary – and he can’t let them down since he is compassionate. Out of his own heartache, he bring riches.

This is the story of the feeing of the 5000. It is the only one of Jesus’ miracles that gets recorded in all four gospels.

The question has surfaced over the years as to why Mark reports it at all. Later evangelists must have asked the same question, as Matthew shortens it markedly and Luke omits it altogether.

The majority opinion is that it serves two key purposes in Mark: it foreshadows Jesus’ own grisly death and it serves as an interlude between Jesus’ sending of the disciples and their return some unknown number of days or weeks later.

Another reason is simply to draw a contrast between the two kinds of kingdoms available to Jesus disciples, both then and ever since. Consider: Mark, tells this story as a flashback, out of its narrative sequence, which means he could have put this scene anywhere. But he puts it here, not simply between the sending and receiving of the disciples but, more specifically, just after Jesus has commissioned his disciples to take up the work of the kingdom of God and when he then joins them in making that kingdom three-dimensional, tangible, and in these ways seriously imaginable.

“Herod’s Kingdom – the kingdom of the world and, for that matter, Game of Thrones and all the other dramas we watch because they mirror and amplify the values of our world – is dominated by the will to power, the will to gain influence over others. This is the world where competition, fear and envy are the coins of the realm, the world of not just late night dramas and reality television but also the evening news, where we have paraded before us the triumphs and tragedies of the day as if they are simply givens, as if there is no other way of being in the world and relating to each other.

Recent Articles, Pentecost 12, Aug. 31, 2025

Pentecost 12 – Compassion and a warning against pride.

Pentecost 12 – Compassion and a warning against pride.

Newsletter Aug. 22, 2025

The readings for the Twelfth Sunday after Pentecost, Proper 17, are unified by the themes of humility and self-giving love as the foundation of a life that honors God. Sirach warns that pride leads to ruin, emphasizing that true power and honor come from the Lord, not from human arrogance. Psalm 112 describes the righteous as generous, just, and fearless, grounded in humility and trust in God. Hebrews exhorts believers to live lives of hospitality, compassion, and praise, reminding them to honor Christ through loving deeds and shared sacrifices. In the Gospel, Jesus teaches a parable about choosing the lowly place at a banquet, underscoring that those who humble themselves will be exalted. Together, these passages call the faithful to embody humility, generosity, and hospitality as expressions of true discipleship.

Lectionary Pentecost 12, Year C

Commentary Pentecost 12

Visual Lectionary, Aug 31, 2025

The Gospel – Luke 14:1, 7-14 – Pentecost 12. The Way Up With God Is Down

Cultural background of the Gospel

Thoughts on Labor Day

Remembering…

Beheading of John the Baptist, Aug 29

Augustine of Hippo, Aug. 28

Lectionary, Aug 24, 2025 – Pentecost 11

I. Theme – The universality of God’s invitation to wholeness and the difficulty of responding to it.

Woman set free from ailment

The lectionary readings are here or individually:

First Reading – Isaiah 58:9b-14 Psalm – Psalm 103:1-8 Epistle – Hebrews 12:18-29 Gospel – Luke 13:10-17

Today’s readings remind us of the universality of God’s invitation to wholeness and the difficulty of responding to it. Isaiah identifies some characteristics of the right relationship with God. The author of Hebrews reminds us that the trials we undergo, though painful, come from the hand of a loving Father who is training us in holiness. Jesus’ words and actions reveal the tension between God’s desire for healing and our need for genuine conversion in order not to hinder God’s plan.

We are all too often concerned about rules—either rules such as the Ten Commandments, which throughout tradition we have assumed were passed down from God—or unspoken rules in society, such as who is in and who is out, who gets to speak and who must be silenced. We become so consumed by rules that we forget the original reason for them. The Sabbath was a gift from God to the people, but some leaders had forgotten and made the Sabbath into following rules. Jeremiah didn’t think he could speak because he was only a boy, and only elders (being men) could speak in public, but God called him to do so anyway. God shows us time and again there is another way—when we love one another, show compassion, have mercy, and do justice for others—we are following God’s ways much more than following a list of rules. The writer of Hebrews shows us that Jesus fulfilled a rule—the rule of sacrifice—in order to break it forever. And so must we follow the rule—the law—of love, in order to break the chains that keep us from loving our neighbors as ourselves.

The Woman in the Gospel is revealing

The story of the woman healed on the Sabbath after 18 years being dominated by an evil spirit is not only a tour de force of Jesus teaching, but it also tells us much about first century Israel.

After healing this women, the Jews object citing the Old Testament prohibition against work on the Sabbath in both Exodus and Deuteronomy. Jesus responds by rebuking the religious leaders for their hypocrisy. They selfishly take care of the needs of their animals on the Sabbath, but then object to meeting the greater spiritual and physical needs of a human being.

The story is framed by passages that give us a glimpse into the culture at the time:

- Sabbath … teaching in one of the synagogues (13:10). Visiting rabbis were often asked to give the sermon or homily for the synagogue service.

- A woman was there (13:11). Though women were excluded from much of Israels religious life, including access to the inner temple court in Jerusalem, they participated in synagogue worship. Jesus gives her a name – the daughter of Abraham indicating her inclusion in the community.

- Crippled by a spirit (13:11). Luke explains that the condition caused her to be stooped over, a condition many commentators have identified as spondylitis ankylopoietica. Verse 16 indicates that this was caused by demonic oppression of some sort. Demons were blamed from much when the cause wasn’t known. Demons are often described as inflicting actual illnesses, including epilepsy (Luke 9:39), muteness (Luke 11:14), lameness (here), and madness (Luke 8:29).

- Synagogue ruler (13:14). This administrative officer maintained the synagogue and organized the worship services.

- There are six days for work (13:14). This verse alludes to the prohibition to work on the Sabbath cited earlier. Notice that the synagogue ruler does not address Jesus directly, perhaps to avoid a direct confrontation or to respect his position.

- Be healed on those days, not on the Sabbath (13:14). The rabbis debated whether it was justified to offer medical help to someone on the Sabbath. It was generally concluded that it was allowed only in extreme emergencies or when a life was in danger. Since this woman’s life is not in immediate danger, the synagogue ruler considers this a Sabbath violation. Jesus does not reject the Torah’s rulings on the Sabbath, only their application. He affirms the role of the Sabbath to bring freedom to people, the original purpose of the Sabbath, in this case from the evil spirit. Both she and the crowd respond with appropriate praise to God.

- Untie his ox or donkey … lead it out to give it water (13:15). The law allowed animals go out on the Sabbath, but restricted the burdens they can carry. While restricting the kinds of knots that could be tied on the Sabbath, the rabbis allowed animals to be tied to prevent straying. They also found ways to water their animals without breaking the limits of Sabbath travel. (Sabbath travel was limited to two thousand cubits, about six-tenths of a mile, from home. They would build a crude structure around a public well, converting it into a private residence. Since the well was now a “home,” animals could be taken there for watering, provided “the greater part of a cow shall be within the enclosure when it drinks.”) Jesus points out the hypocrisy of taking such measures to protect one’s property while objecting to an act of human compassion.

- Then should not this woman … be set free on the Sabbath… ? (13:16). If an animal can be helped on the Sabbath, how much more a human being. Both the animal and women are set free, the latter by untying and the latter by Jesus. She is also blamed by the synagogue leader for being in need. He chooses to go after her rather than Jesus who it not rebuked

- His opponents were humiliated (13:17). A great orator in this time was one who could baffle and silence his opponents. It is clear that Jesus had won this one. Of course, the story is more than a clash between cultures, it is reflective of Jeus sense of compassion toward others.

Gospel – “Woman, You are Set Free”

Here is the scripture from Luke 13:10-17 for this week

Jesus continues on the road to Jerusalem but there is a change in venue. Jesus had been speaking to disciples and large crowds. Now, he appears in "one of the synagogues." His presence in a synagogue is his first since leaving Galilee, and he will not visit another in Luke’s gospel. The conflict with Jewish leaders he will experience then is foreshadowed this story.

Jesus enters the synagogue and he seems to be in search of something. Just before this scene, Luke records a parable in which Jesus’ vineyard owner says, “For three years I have come looking for fruit on this fig tree, and still I find none” (Luke 13:7). His sensitivity is heightened as he continues to search for “fig trees” that are bearing fruit.

He enters the synagogue immediately following this parable and will heal a Jewish lady who has been suffering for 18 years. Jesus heals the woman in sacred space (a synagogue, mentioned twice) and within sacred time, namely on a Sabbath (noted no fewer than five times), and he is criticized for this breach of the law. Jesus insists that the synagogue and the Sabbath are not the only things that are holy — so is this woman’s life. He is also guilty of touching a ritually unclean woman in their eyes. Jesus isn’t abolishing the Law of Moses, but helping the people in the synagogue have a better understanding of how to apply the law.

This isn’t his first healing in Luke. Earlier, in Chapter 4, Jesus heals a man with an unclean spirit. In Chapter 6, he healed a man whose hand was withered. On both occasions, Luke describes Jesus teaching in a synagogue on the Sabbath, but we are not informed about the content of his teaching. On both occasions, prominent religious leaders take offense at Jesus’ actions because of their view of what is allowable on the holy Sabbath day. By the end of chapter 13, Jesus’ search will turn into lament, “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem…” (cf. 13:34-35).

Jesus’ rebuttal is clever, for while untying an ox or a donkey on the sabbath was forbidden in one part of the Mishnah (a Jewish book of laws), it was permitted in another. His point is that the woman is far more important than animals, yet animals are allowed more freedom on the sabbath than is the woman. This woman is a "daughter of Abraham," heir to the same promise as Abraham.

Note the story is not about his teaching or even the faith of the people. Both stories are healing stories but, more significantly, for Luke, is the controversy these healings created due to questions of Jesus’ Sabbath practices. He doesn’t argue about Judaism, or the restriction.

So what is it all about ?

1. It is story of the Kingdom – a story of community. Healings and exorcisms are signs of the kingdom of God. In verse 12, "Jesus saw" is in the primary position in the sentence, a subtle emphasis.

Jesus seems to be ignored by the Jewish leaders. The “leader” (v. 14) speaks to the “crowd”, but his words are directed at Jesus. He is blind to God’s kingdom. The people in the synagogue seem blind to her presence also

After he saw her, he called her to him. Marginalized and in the shadows, the woman is brought to center stage by Jesus. He sees the person, not the condition. In the new world of Jesus, it is precisely people such as the "bent woman" who are moved from the periphery of society to the center, which is what Jesus has done here. He argues from legitimate allowances of restricted kinds of "work" on the Sabbath. There is a higher calling – all life as sacred.

One key point here is that the woman does not ask to be cured; no one asks on her behalf; Jesus notices her. How many do we notice in our lives that need to be freed ? We need to be observant extending the kingdom

The woman has done nothing to earn or even request this unfathomable gift of life/grace. Her response is one of standing up, living into the gift of grace, and publicly praising God

What are the human-imposed barriers (even well-intentioned ones) that prevent people from experiencing God’s grace? How do we, God’s stewards today, help to dismantle these barriers?

2. It is a story of freedom from bondage

Jesus operates within the confines of Judaism but there is a limit when one is suffering. He won’t exclude them based on religious customs to provide healing. He demonstrates his compassion and thus to us a way of life, a way to live out our community obligations. Both themes of praise and rejoicing are emphasized by Luke as appropriate responses to God’s work in Jesus the one who brings the reign of God in healing power to those who most need it.

Her problem is both medical and social. She is “crippled” but has been been ostracized from the Jewish community. At the time many human ailments were seen to be cause by Satan; the very being of someone with a serious ailment was thought to be hostile to God. (She is not under demonic possession.)

In verse 16, Jesus himself will attribute the woman’s "weakness" to being held in bondage by Satan. What is called for, then, is not just medical healing but release from bondage. She has suffered and been ostracized from the Jewish community.

The point of confrontation is on the role of the Sabbath. Does it mean just following the prescribed order of worship each week? Does it mean following the ceremony to the letter of the law no matter what happens?

There are two traditions concerning the Sabbath. One, recorded in Exodus 20, links the Sabbath to the first creation account in Genesis, where God rests after six days of labor. As God rested, so should we and all of our households and even animals rest. The second tradition, in Deuteronomy 5, however, links the Sabbath to the Exodus; that is, it links Sabbath to freedom, to liberty, to release from bondage and deliverance from captivity. Jesus is causing the Jewish leaders to remember this passage. The Sabbath is all about freedom and this scripture concerning the woman. How might we be encouraged to act on Sunday to provide hope and joy

Jesus reminds the Sabbath leader that, regardless of the day of the week, all of God’s creation must have access to God’s gifts of life – whether it’s the provision of water for God’s creatures (v.15) or manna on the sabbath for the Israelites in the wilderness

Jesus has taken the synagogue leader’s very argument, and its same scriptural source, and turned it against him. Jesus’ message is clear: "If the sabbath is about freedom, as your own passage from Deuteronomy clearly says, then it is entirely proper to celebrate the freedom of this woman from the bondage of Satan–yes, on the sabbath, even especially on the sabbath."

One might criticize Jesus for discussing the situation ahead of time with the Jewish leaders. However, as Jesus maintained last week , he came to cast fire on the earth and cause divisions.

How do we go beyond our bondages ? By forgiving those who have sinned against us, we are freed from bondage to resentments and feelings of revenge. By forgiving ourselves, we are released from continually beating up on ourselves for acting so stupidly or hurtfully. Forgiveness brings release and freedom. Thus, this text isn’t just about physical healing, but renewal that we all need.

Healing begins when people are seen as Jesus would see them:

- With unconditional acceptance

- With appreciation for their person and not their problem.

- With vision for their potential and not their limitations

The ending is significant going back to the growing confrontation with the Jewish authorities In Luke 6, the religious leaders depart from the synagogue trying to think of what to do with Jesus; and, they were furious (6:11). Their negative response will have major consequences later in the narrative. In Luke 13, the synagogue crowd rejoices at Jesus’ healing action (and teaching?). And, here, his “opponents” are disgraced. And that provides a greater motive for them in Jerusalem.

A Word or Two for each Reading

For Proper 15, Year C, Pentecost 10 , the readings center around themes of divine judgment, prophetic truth, and the tension between peace and division. Here are several key words and phrases that emerge from the appointed texts:

🔥 Thematic Keywords

Jeremiah (Track 2)

Prophecy & Truth – Jeremiah 23:23–29 contrasts false dreams with the power of God’s word

Hammer & Fire (God’s Word) – Metaphors for divine truth breaking through deception (Jeremiah 23:29)

Isaiah (Track 1)

Vineyard – Symbol of Israel and divine expectation (Isaiah 5:1–7)

Justice & Righteousness – God’s desired fruits, contrasted with bloodshed and cries (Isaiah 5:7)

Psalm 82

Rescue &Deliverance – Psalm 82 calls for justice for the weak and needy

Hebrews

Faith – Central to Hebrews 11:29–12:2, highlighting perseverance and trust in God’s promises

Cloud of Witnesses – A poetic image of spiritual ancestors encouraging endurance (Hebrews 12:1)

Luke

Fire – Both destructive and purifying; Jesus speaks of bringing fire to the earth (Luke 12:49)

Division – Jesus foretells familial and societal division as a consequence of his mission (Luke 12:51–53)

Interpretation of Signs – Jesus critiques the crowd’s inability to discern spiritual realities (Luke 12:54–56)

Lectionary commentary Pentecost 10, August 17

I. Theme – The connection between speaking out for God and making enemies

National Cathedral – “Fire Window”

The lectionary readings are here or individually:

First Reading – Jeremiah 23:23-29

Psalm – Psalm 82

Epistle – Hebrews 11:29-12:2

Gospel – Luke 12:49-56

Today’s readings recognize the connection between speaking out for God and making enemies. In Jeremiah , God denounces those false prophets who tell lies in God’s name. The author of Hebrews urges believers to accept hardship as a divine aid to discipline. There are no guarantees that the faithful will thrive. They may be the objects of persecution and violence, but even in adverse situations, their hearts and minds are focused on God’s realm. This may minimize the emotional impact of persecution. Jesus warns that his ministry will bring a time of spiritual crisis.

When we ignore the poor, when we turn away from the cries of injustice in this world, we turn away from Jesus himself. In Jesus’ day, the religious hypocrites would claim to follow God’s ways but had no concern for the very ones God declared concern for through the prophets. To this day, we end up being concerned more about right belief and right doctrine than how we live out our faith. When we look to the prophets and to Jesus, we see God hearing the cries of the poor, the widows and the orphans. We see Jesus eating among the sinners and tax collectors and the prostitutes. We hear the rejection of Jesus by others being a rejection of God’s love for all people, but especially the marginalized and outcasts. This same rejection happens today—we fashion Jesus into being concerned about right belief, when Jesus seems clearly to be concerned with how we love one another. We continue to miss the mark, transforming a love for all, especially those on the margins, into a love for a few who are obedient to a set of rules.

In the maelstrom of conflicting positions and cultural divisions, Jesus challenges us to interpret the signs of the times. Awareness opens us to see the connection between injustice and violence and consumerism and ecological destruction. The causal network has a degree of inexorability: although we are agents who shape the world, we do reap what we sow.

Gospel, “I came to bring fire to the earth, and how I wish it were already kindled! “

This a shift of mood in the gospel from last week’s Luke 12:32-48. That passage begins with a beautiful theme of blessing for the crowd. “Do not be afraid, little flock” to this week’s “Do you think that I have come to bring peace to the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division!” Now there’s a shift !

This a shift of mood in the gospel from last week’s Luke 12:32-48. That passage begins with a beautiful theme of blessing for the crowd. “Do not be afraid, little flock” to this week’s “Do you think that I have come to bring peace to the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division!” Now there’s a shift !

When he is with the crowd, strangers and foreigners, he proclaims the Good News of God’s unconditional acceptance and universal compassion. When Jesus is with the disciples, his teaching is far more demanding and often blunt.

Contradicting the angels’ promise of peace on earth at his birth in Luke 2, Jesus emphatically denies that he’s come to bring peace. Instead, he claims to be the bearer of discord and fragmentation. As he journeys toward Jerusalem, Jesus becomes a source of conflict and opposition when he lays claim to startling forms of authority and power. His words are marked with a sense of urgency and intensity. The road to Jerusalem, after all, leads to a violent confrontation with death.

"Fire Window" – National Cathedral, Washington

This week’s gospel can be divided into three parts :

1 In verses 49-53, there are three images – casting fire, baptism/immersion , division of family members

At least with the first two images, fire and baptism, Jesus’ is distressed that he hasn’t completed these tasks. By placing this saying in the midst of the journey narrative — Jesus is on his way to Jerusalem but not there, yet — Luke may be indicating that the completion of these tasks takes place on the cross in Jerusalem when he is "immersed" into death, or, in a broader sense, his immersion into the passion/suffering events that take place in Jerusalem

Jesus explains the way in which His coming will “cast fire on the earth.” He also expresses an eagerness to get on with the process of bringing fire to the earth. This “fire” has implications for the family, but not those which we would prefer. The coming of Christ will cause great division within families, driving wedges between those family members between whom we normally find a strong bond.

What is this fire ?

One possibility of the “fire” of which Jesus spoke is the same fire about which the prophets, including John the Baptist, spoke—the fire of divine wrath. When Jesus said that He had come to “kindle a fire” – the outpouring of God’s wrath on sinful Israel/ His death on the cross would set in motion a series of events, which will eventuate in the pouring forth of God’s divine wrath on sinners.

Another possibility is to consider the phrase “begin on fire” to refer to someone who is passionate about something. We need to get rid of things that exploit and do not sustain us (such as poverty, racism, disease). Redemption can come only when those systems are shattered and consumed by fire and we rebuild based on a different set of values. Business as usual means injustice and death. Thus, life can not flourish with a crisis which is God’s presence.

Thirdly, it can also speak to Jesus transformation – from man to resurrected individual and the change. His purpose was to become a sacrifice for our sins and his baptism was the crucifixion. His death on the cross would set in motion a series of events, which will eventuate in the pouring forth of God’s divine wrath on sinners and the creation of the church

One needs to separate the idea of “means” and “end” in this passage . The difference is, on the one hand, that between “then” (heaven, the kingdom of God) and “now.” “Peace” is the end, but a sword and division is the means. “Life” is the end, but death—our Lord’s death, and the disciple’s “taking up his cross” is the means

Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote from his German prison cell in 1944 about the violence which destroyed the sense of fulfillment of life for him and the long isght of history. Out of this painful experience came a profound insight, part of his Daily Meditations from His Letters: “This very fragmentariness may, in fact, point toward a fulfillment beyond the limits of human achievement."

What is this baptism ? This part of the scripture refers to Jesus himself and not his followers. Not immersion in water but tis baptism is clearly the death which He would die on the cross of Calvary. He is being cleansed for a purpose . His purpose was to become a sacrifice for our sins and his baptism was the crucifixion. It can refer also to his mission against the structures of the world about which he is “stressed” since it will lead to his own death. Yet, there is relief when it is over.

The division which Jesus speaks of here has several interesting features. Following Jesus is more than just affirming his message – it is teaching of action which has its consequences. First, there is a division which occurs within the family.

-father against son

-mother against daughter

-mother-in-law against her daughter-in-law

Peter Wood speculates that Jesus may have meant, 1. Conflict within the order of Rome, the cult of the emperor. 2. Conflict within Jewish families with the importance of the mother determining who is Jewish. 3 Conflict within entities themselves such as within believers, or today within churches,

Second, there is a polarization which is described, so that it is not “one against one,” or to follow the imagery established by our Lord, “one against four,” but “two against three” and “three against two.” All these numbers don’t divide evenly. Is this the origin of “being at odds with someone”?

Those who have come to faith in Christ will join together into a new kinship, while those who have rejected Christ will also find a new bondage, a new basis of unity, in opposition to Christ

As Phyllis Tickle writes, “All change – even Good News change – will cause conflict and grief for the simple reason that all change – even Good News change – means giving up / losing something, and it means valuing one thing over another.” Out of the old traditional family comes a new family of believers. This was a challenge to the biological family in that time, extremely important. You risk being cast out – an extraordinary demand.” You risk your own baptism on the cross.

Jesus warned that those who make a commitment to him will be persecuted, that a commitment of faith also means that our attitude toward material possessions must change, and that moral responsibilities must be taken with even greater seriousness. Because our commitment to Christ shapes our values, priorities, goals, and behavior, it also forces us to change old patterns of life, and these changes may precipitate crises in significant relationships

2 In verses 54-57, Jesus speaks specifically to the multitudes, pointing out a very serious hypocrisy. He reminds them that while they can forecast tomorrow’s weather by looking at present indicators, they cannot see the coming kingdom of God as being foreshadowed by Christ’s first coming.

The illustration seems to point to the weather patterns in the Near East. The Mediterranean Sea was to the west and winds from that direction brought rain. The desert was to the south and winds from that direction brought heat.

He calls the religious leaders hypocrites. He criticized them and also his hearers about their lack of ability to perceive spiritual realities around them. Why, then, could these people, skilled at reaching conclusions about the weather, not come to the conclusion that Jesus was the Messiah, based on the voluminous evidence, all of which conformed perfectly to the predictions of the prophets?

You can look at this in another way and see the implications of our own lives. It is time to check the direction of the wind and let that determine the course of action. We tend to let the insignificant dominate our attention while miss or ignore the significant. Our actions help to determine the future as natural consequence follow from the weather

3 Verses 58 and 59 conclude the chapter by making a very personal and practical application. Reconciliation with their opponent needs to take place prior to standing before the judge.