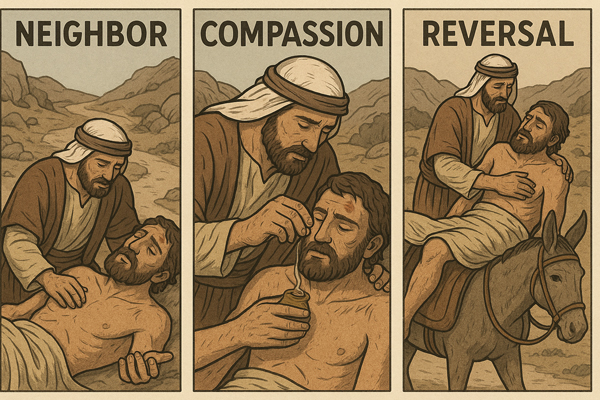

Focus on Neighbor:

The Parable of the Good Samaritan is a pivotal moment in Luke’s Gospel, where Jesus radically redefines the prevailing understanding of ‘neighbor.’ The lawyer’s initial question, ‘Who is my neighbor?’ (v. 29), likely stemmed from a desire to limit his obligation to those within his own community or religious group. However, Jesus shatters these comfortable boundaries. By choosing a Samaritan – a person ethnically and religiously despised by the Jews – as the hero, Jesus forces his audience to confront their prejudices. The ‘neighbor’ is not defined by proximity, shared heritage, or religious affiliation, but by one’s capacity for compassion and action in the face of another’s need, regardless of who that ‘other’ might be. This parable challenges us to look beyond our ‘in-groups’ and extend love and practical help to anyone we encounter who is suffering, even our perceived enemies.

Focus on Practical Compassion and Costly Love:

Beyond the theological implications, the Good Samaritan offers a powerful blueprint for practical, costly love. Notice the detailed actions of the Samaritan: he ‘had compassion,’ ‘bandaged his wounds,’ ‘poured on oil and wine,’ ‘set him on his own animal,’ ‘brought him to an inn,’ and ‘took care of him’ (vv. 33-34). Crucially, he also made a financial commitment, giving the innkeeper ‘two denarii’ and promising to pay more if needed (v. 35). This isn’t just about feeling pity; it’s about active, self-sacrificial involvement. The priest and the Levite, by contrast, prioritized ritual purity or personal convenience over the desperate need before them. The parable underscores that true neighborliness isn’t just a sentiment, but a tangible commitment that often involves inconvenience, expense, and a willingness to step outside our comfort zones to alleviate another’s suffering.

Focus on the Ironic Reversal and Challenging Self-Righteousness:

One of the most striking elements of the Good Samaritan parable is its ironic reversal of expectations, designed to challenge the self-righteousness of Jesus’ audience, including the inquiring lawyer. The figures who would have been considered ‘pious’ and ‘righteous’ – the priest and the Levite – utterly fail in their moral duty. It is the Samaritan, a member of a despised and heretical group, who embodies true righteousness and fulfills the spirit of the Law. This reversal is profoundly uncomfortable because it upends conventional wisdom and exposes the hypocrisy that can lurk beneath outward religious observance. Jesus essentially asks, ‘Who truly lived out the command to love God and neighbor in this scenario?’ The answer is startlingly clear: not the religious elites, but the one they looked down upon. This forces us to examine our own assumptions about who is ‘worthy’ or ‘unworthy’ of our compassion and reminds us that true faith is demonstrated through merciful action, not just adherence to rules or social status.