Research indicates Samaritans emerged as a distinct community during the Persian (550-330 BCE) and Hellenistic periods (323-31 BCE), solidifying their identity in opposition to the Jewish community centered in Jerusalem. The construction of their temple on Mount Gerizim, possibly in the 5th or 4th century BCE, marked a definitive split, establishing a rival center of worship to the Jerusalem Temple.

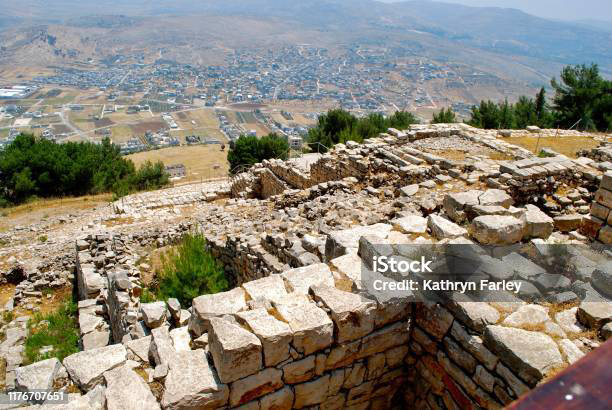

Mt. Gerizim.

Mt. Gerizim.

Samaritanism shares many foundational elements with Judaism, yet differing significantly in key aspects. Their sacred text is the Samaritan Pentateuch, their version of the first five books of Moses (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy). They reject all other books of the Hebrew Bible (Prophets and Writings) and the Oral Law (Mishnah, Talmud) that are central to rabbinic Judaism.

According to Samaritan tradition, they are direct descendants of the Israelite tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh (sons of Joseph), and Levi, who remained in the land of Israel after the Assyrian conquest of the Northern Kingdom in 722 BCE. They assert that they are the true inheritors of the Mosaic tradition, having preserved the original worship of God on Mount Gerizim, as commanded by Moses.

The central tenets of Samaritan belief, often summarized as the “Samaritan Creed,” include:

One God: Belief in one God, the God of Israel.

One Prophet: Belief in Moses as the only prophet.

One Book: Belief in the Samaritan Pentateuch as the only holy scripture.

One Holy Place: Belief in Mount Gerizim as the chosen place of God’s dwelling and worship, rather than Jerusalem.

One Day of Judgment: Belief in a Day of Judgment and a coming Taheb (a messianic figure, similar to Moses).

The relationship between Samaritans and Jews has been complex and often adversarial for millennia. The biblical accounts of Ezra and Nehemiah depict a refusal by the Samaritans to participate in the rebuilding of the Jerusalem Temple, leading to mutual excommunication and hostility. This animosity is famously illustrated in the New Testament parable of the Good Samaritan, where Jesus uses a Samaritan as an example of compassion, precisely because Samaritans were typically despised by Jews of that era.

In the scripture this week in Luke 9, the tensions between Samaritans and Jews are apparent, between Samaritans and Jesus’ disciples. And in Luke 10, in a few weeks in the “Good Samaritan” parable, Jesus makes the audacious move of casting a Samaritan as the hero of a story about following Jewish law.

From the SALT Blog

“In Luke 9, the fact that Jesus was bound for Jerusalem is what made him unwelcome from the Samaritan point of view. No sooner has Jesus “set his face” toward Jerusalem than he’s rejected for that very reason — a clear case of what today we’d call, ‘religious intolerance.'”

“Jesus’ disciples respond in kind, furiously asking Jesus if they should call on God to rain down fire and destroy the Samaritans. Nope, “So far from destroying your neighbors who believe differently than you do, you should be humble enough to learn from them, and follow their lead!”

After this they encounter three possible disciples but each of them wanted exceptions for not following Jesus immediately. To the first, don’t expect ideal accommodations. The second said “sure but let me take care of family responsibilities” – let me bury my father. That won’t work since those things are not part of what we are doing today. The last one wanted to say goodbye to those at home. That won’t work as we are looking forward.

What we should take away is that we should not get hung up by the past and conflicts with the Samaritans and embrace new challenges. How we can proclaim God’s reign and Kingdom and Jesus message – of loving one’s neighbor as oneself, extending this love to enemies as well as focus on our faith, prayer and repentence.