1. Food Waste

The local food banks and other distributors have worked out agreements with restaurants to help eliminate waste by taking foods they cannot sell due to sell by dates and redistributing the foods. Globally, the issue of waste is a large one.

World Wildlife Federation has covered the topic in its Fall, 2018 magazine.

“Today, 7.3 billion people consume 1.6 times what the earth’s natural resources can supply. By 2050, the world’s population will reach 9 billion and the demand for food will double.

“So how do we produce more food for more people without expanding the land and water already in use? We can’t double the amount of food. Fortunately we don’t have to—we have to double the amount of food available instead. In short, we must freeze the footprint of food.

“In the near-term, food production is sufficient to provide for all, but it doesn’t reach everyone who needs it. In fact, one-third of the world’s food—1.3 billion tons—is lost or wasted at a cost of $750 billion annually. When we throw away food, we waste the wealth of resources and labor that was used to get it to our plates. In effect, lost and wasted food is behind more than a quarter of all deforestation and nearly a quarter of global water consumption. It generates as much as 10% of all greenhouse-gas emissions. As it rots, it pollutes water and soil and releases huge amounts of methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gases.

“Another negative aspect of food waste is its connection to species loss. Consider this: Food production is the primary threat to biodiversity worldwide, expected to drive an astonishing 70% of projected terrestrial biodiversity loss by 2050. That loss is happening in the Amazon, where rain forests are still being cleared to create new pasture for cattle grazing, as well as in sub-Saharan Africa, where agriculture is expanding rapidly. But it’s also happening close to home.

“These wasted calories are enough to feed three billion people—10 times the population of the United States, more than twice that of China, and more than three times the total number of malnourished globally. Wasted food may represent as much as 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and is a main contributor to deforestation and the depletion of global water sources.

“By improving efficiency and productivity while reducing waste and shifting consumption patterns, we can produce enough food for everyone by 2050 on roughly the same amount of land we use now. Feeding all sustainably and protecting our natural resources.”

South Korea has a system that keeps about 90 percent of discarded food out of landfills and incinerators, has been studied by governments around the world. But the country’s mountainous terrain limits how many landfills can be built, and how far from residential areas they can be built.

Since 2005, it’s been illegal to send food waste to landfills. Local governments have built hundreds of facilities for processing it. Consumers, restaurant owners, truck drivers and others are part of the network that gets it collected and turned into something useful.

In the case of a restaurant when it gets to a plant. Debris — bones, seeds, shells — is picked out by hand though most facilities are automated. A conveyor belt carries the waste into a grinder, which reduces it to small pieces. Anything that isn’t easily shredded, like plastic bags, is filtered out and incinerated.

Then the waste is baked and dehydrated. The moisture goes into pipes leading to a water treatment plant, where some of it is used to produce biogas. The rest is purified and discharged into a nearby stream.

What’s left of the waste at the processing plant, four hours after Mr. Park’s team dropped it off, is ground into the final product: a dry, brown powder that smells like dirt. It’s a feed supplement for chickens and ducks, rich in protein and fiber, said Sim Yoon-sik, the facility’s manager, and given away to any farm that wants it.

For consumers, at apartment complexes around the country, residents are issued cards to scan every time they drop food waste into a designated bin. The bin weighs what they’ve dropped in; at the end of the month they get a bill.

2. Food in Biblical times

All of us whether we are food secure or not have to be concerned with how our food choices are affecting the environment, God’s creation.

You could make the point that diets were healthier in Biblical times and there was better care of the environment.

Originally God granted the use of the vegetable world for food to man ( Genesis 1:29 ). Many foods we encourage people to eat were a regular part of Biblical diets. These include olives and olive oil, pomegranates, grapes, goat milk, raw honey, lamb, and bitter herbs. Fruit was another source of subsistence: figs stood first in point of importance; they were generally dried and pressed into cakes. Grapes were generally eaten in a dried state as raisins. Of vegetables most frequently mentioned were lentils, beans, leeks, onions, and garlic ( Numbers 11:5 ) Honey is extensively used, as is also olive oil.

Meat consumption was limited in contrast to today. In the law of Moses there are special regulations as to the animals to be used for food ( Leviticus 11 ; Deuteronomy 14:3-21 ). “You may eat any animal that has a divided hoof and that chews the cud”. Certain animals were mentioned that could not be eart- rabbit, pig, camel Most birds were seen as unclean. Most fish could be eaten but must have “fins and scales. ” The Jews were also forbidden to use as food anything that had been consecrated to idols ( Exodus 34:15 ), or animals that had died of disease or had been torn by wild beasts ( Exodus 22:31 ; Leviticus 22:8 ) or animals that moved along the ground ( Leviticus 11 ). The animals killed for meat were –calves, lambs, oxen – not above three years of age, harts, roebucks and fallow deer; birds of various kinds.

Foods today

- The food we eat affects our health- in particular corn and soy.

Today, we are getting less nutrition for the same amount of food due in part to depletion of nutrients in the soil due to our decision on what to grow, in particular corn and soy. Two of the cheapest sources of calories are corn and soy, which the federal government has long subsidized and which make up a large percentage of our caloric intake today (often in the form of high fructose corn syrup or soybean oil). Corn is also a large part of the diet of the animals we eat.

Corn and soy are prized because they can be efficiently grown on vast farms. But growing just one crop consistently (a monoculture) depletes the soil and forces farmers to use greater amounts of pesticides and fertilizers.

According to Brian Halwell, a researcher for WorldWatch, vitamin C has declined by 20 percent, iron by 15 percent, riboflavin by 38 percent, and calcium by 16 percent. So we are now getting less nutrition per calorie in our foods. In essence, we have to eat more food to get the same vitamin and mineral content.

This is probably due to a combination of factors, including the depletion of nutrients in the soil through monoculture and the use of fertilizers, which simplify the biochemistry of the soil.

This simplification of the soil in turn makes plants more vulnerable to pests, so farmers need to use more pesticides, which introduces those chemicals (environmental toxins) in our bodies and in our air and water supply.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s Report on Environmental Pollution and Disease indicates that the following common diseases and conditions may be strongly linked to environmental exposure: asthma, autism, breast and other cancers, lung disease, Parkinson’s disease, and conditions associated with reproductive health.

- Corn and soy affect the quality of US Streams

A US National Academy of Science report designates nitrogen and phosphorous pollution as the main threat to US Coastal Waters. Moreover, according to a recent EPA report 55% of all US streams are now unsuitable for aquatic life primarily due to excess nutrients. The basic problem is that fertilizer runoff from corn production used primarily to feed livestock and leaching from large manure ponds found

Adding nutrients stimulates excess growth of phytoplankton (algae) that subsequently then die and sink to become available for bacteria to decompose in bottoms waters. As bacteria decompose the dead phytoplankton they also consume oxygen. Consequently, increasing nutrient additions indirectly leads to increases oxygen consumption by the bacteria until most or even all of the oxygen is removed from the water

- Our food choices affect levels of greenhouse gases

The food we eat is responsible for almost a third of our global carbon footprint. Red meat is the most emissions-intensive food we consume.

The “carbon footprint” of hamburger, for example, includes all of the fossil fuels that went into producing the fertilizer and pumping the irrigation water to grow the corn that fed the cow, and may also include emissions that result from converting forest land to grazing land. Meat from ruminant animals (cows, goats, and sheep) has a particularly large carbon footprint because of the methane (a potent global warming gas) released from the animals’ digestion and manure.

Producing livestock for human consumption contributes 14.5% of annual global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Greenhouse emissions causes a warming of the planet. These temperatures exceed the heat tolerance of major crops, so that yields of these crops will decline. One way to reduce the food security problem is to shift global diets toward one that is more plant-based

Mark Bittman in Food Matters estimate “In all, the average American meat eater is responsible for one and a half tons more CO2-equivalent greenhouse gas—enough to fill a large house—than someone who eats no meat

However, it is possible to substitute red meat with other meats, or plant-based protein sources, such as lentils and nuts, that have a lower impact.

Another issue with livestock is that overgrazing by livestock has caused a loss of top soil.

- Overall we are eating less diverse. Modern farming methods mean 75% of the world’s food comes from just 12 plants and five animal species.

This lack of diversity in our food supply makes it much more vulnerable to climate change, pest,s and diseases

The world of junk food, overrefined carbohydrates, and highly processed oils make up an astonishingly large part of our diet, according to Mark Bittman in Food Matters. Meanwhile, beef, pork, dairy, chicken, and fish account for 23 percent of our total caloric consumption, while vegetables and fruit—including juice, which is often sugar-laden—barely hit 10 percent

| Rank | Food | % of Total Energy |

| 1 | Sweets, desserts | 12.3 |

| 2 | Beef, pork | 10.1 |

| 3 | Bread, rolls, crackers | 8.7 |

| 4 | Mixed dishes | 8.2 |

| 5 | Dairy | 7.3 |

| 6 | Soft drinks | 7.1 |

| 7 | Vegetables | 6.1 |

| 8 | Chicken, fish | 5.7 |

| 9 | Alcoholic beverages | 4.4 |

| 10 | Fruit, juice | 3.9 |

To give you an idea of how much more energy goes into junk food than comes out, consider that a 12-ounce can of diet soda—containing just 1 calorie—requires 2,200 calories to produce, about 70 percent of which is in production of the aluminum can. Almost as impressive is that it takes more than 1,600 calories to produce a 16-ounce glass jar, and more than 2,100 to produce a half-gallon plastic milk container. As for your bottled water? A 1-quart polyethylene bottle requires more than 2,400 calories to produce

Every time you drink a glass of tap water instead of bottled water, you save the calorie equivalent of a day’s food: the 2,400 calories it takes to produce that plastic bottle.

To do

- Eat locally and organically

Buying locally can help reduce the pollution and energy use associated from transporting, storing and refrigerating this food—that’s especially true for food that is imported by airplane

Choose locally caught, sustainably managed fish or herbivorous farmed stocks like tilapia, catfish, and carp

Organic farmers don’t use chemical fertilizers or pesticides, and farm using high quality animal welfare practices.

- Eat a more balanced diet which helps to break down toxins in our body

a Drink extra water.

b Consume a balanced diet of whole foods, colorful fruits, and vegetables, such as broccoli, squash, blueberries, citrus, beets, dandelion greens, artichokes, pomegranate, and carrots. These foods are filled with phytonutrients and have been shown to boost detoxification.

c Eat celery-an “unassuming” but powerful detoxifying food that provides phytonutrients that benefit the liver’s ability to detoxify. Include the following foods containing antioxidants (vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, and selenium): beets, broccoli, asparagus, swiss chard, kale, peaches, red peppers, papayas, parsley, carrots, apricots, alfalfa, avocados, cantaloupe, and green leafy vegetables. Antioxidants are necessary for neutralizing free radicals.

Eating this way saves energy. From Food Matters. “Look at it this way: When you eat a quarter pound of beef, you’re consuming about 20 percent of your daily calories, but it takes about 1,000 calories—almost half your daily intake—to produce that burger. Remember, beef production requires energy for processing, transportation, marketing, and, most of all, the production of all the grain fed to the cow in the first place. (Producing a salad requires energy too, but nothing like what it takes to make that quarter-pounder.)”

Mark Bittman’s conclusion in Food Matters –“The choice is obvious: To reduce our impact on the environment, we should depend on foods that require little or no processing, packaging, or transportation, and those that efficiently convert the energy required to raise them into nutritional calories to sustain human beings. And as you might have guessed, that means we should be increasing our reliance on whole foods, mostly plants.”

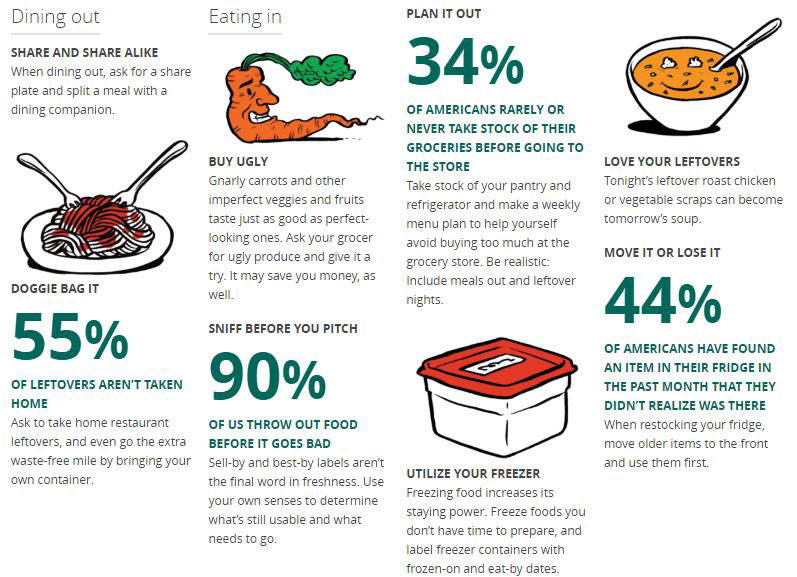

- Watch the waste.

The USDA estimates that an astonishing 27 percent of all food (by weight) produced for people in the United States is either thrown away or is used for a lower-value purpose, like animal feed. A recent study estimated that the average household wastes 14 percent of its food purchases—a loss of significant value for most families

In addition to the water, energy, pesticides, and global warming pollution that went into producing, packaging, and transporting this discarded food, nearly all of this waste ends up in landfills where it releases even more heat-trapping gas in the form of methane as it decomposes.

Avoid products with a lot of packaging.

Compost your kitchen scraps with your yard leaves and lawn clippings.

- How we grow is also important.

It’s also important to note that the importance of “water use” is not the same everywhere; the water use we measured included rainfall, groundwater extractions, and surface water diversions for agriculture. But in terms of sustainability, using rainwater to grow crops has much less environmental impact than depleting underground aquifers or diverting water from rivers. There are other trade-offs between environment and health as well. For example, sugar and oil have lower greenhouse gas emissions than many meats, but eating these in large amounts is unhealthy

- Consider the life cycle of everything you take into your hand.

Where did it come from? Who made it and under what conditions? What were the costs to the environment and to people to grow or manufacture this item? How far did it travel? What will happen to it when it is broken and needs to be discarded?