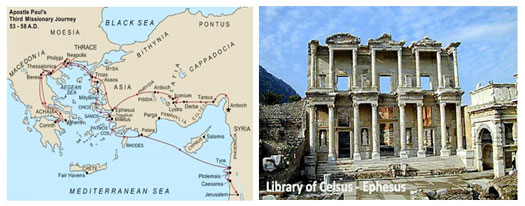

The western quarter of Turkey was called Asia Minor during the Roman period, and Ephesus was its largest city and the center for criminal and civil trials. The city’s theater sat facing the sea at the head of the main road from the harbor into the city. Ephesus had a troubled history with Rome. In the first century BCE, Roman tax collectors and businessmen had run roughshod over the province, outraging the locals with their exploitation and extortion. The Ephesians welcomed the challenge to Roman hegemony posed by an invading eastern king, and with his capture of the city in 88 BCE, its citizens joined in the massacre of the city’s Italian residents. Rome responded with a characteristically firm hand, exacting huge penalties and taxes to keep the city without resources. The economy did not recover until the reign of Augustus.

And, as in Jerusalem, Corinth and Athens, Ephesus attracted a large number of tourists, though smaller than modern standards. Pilgrims came to Ephesus to see the Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. This temple had been destroyed and rebuilt many times over the centuries. The temple Paul would have seen was erected in the fourth century BCE; a forest of marble, it had 127 columns measuring 1.2 meters in diameter, standing 18 meters high. It was a refuge for runaway slaves, and was outside the city proper. The form of Artemis worshipped here was unlike anywhere else, perhaps because she had been assimilated with a local Anatolian earth goddess. Unlike the virgin huntress and twin sister of Apollo most familiar in the stories of the Greeks, Artemis at Ephesus was a fertility goddess, and her physical manifestation was a statue of the goddess festooned with oval protuberances — probably representing testicles of sacrificial bulls — and she wore a stole of bees. Acts repeats a story of how Paul’s success threatened the livelihood of those citizens who relied on proceeds from visitors to the Temple of Artemis.

When Paul arrived in Ephesus, Priscilla and Aquila greeted him, introduced him to the congregation that met at their house and briefed him on the status of the local movement. According to Acts, Ephesus had believers who had been baptized by disciples of John the Baptist and followed a teacher named Apollos. He had since left Ephesus for Corinth, with a letter of introduction from Aquila and Priscilla. The Ephesus community knew the teachings of Jesus, but had not heard Paul’s message of the holy spirit. Similar variations, and sometimes rivalry, must have marked many early congregations, varying by teacher, local tradition, and communications with other cities. In his circuit of travels, Paul tried to establish some continuity. Paul would spend three years in Ephesus, and may have been imprisoned for some of that time. His letters indicate that he made visits to Corinth during his stay. And, as in Corinth, Paul earned his keep working as a tentmaker when he could, and depended on the support of his congregations when he could not. With this support he was able to spread his message even while under arrest.

Most of Paul’s surviving letters were probably written during his time in Ephesus. The sequence and authenticity of the letters have been debated in recent generations, and it seems forged or misidentified letters were already a problem during Paul’s lifetime. Since most of his letters were dictated, Paul made a point to personally sign his letters, and asked his readers to look for his distinctively large letters. It also seems that letters were shared between the nascent communities — either copied or circulated and moving from city to city with the traveling teachers and companions. The letters themselves are testimony to the frequency of travel. While there was a military postal service, it was reserved for the official business of Empire. Letters like Paul’s would have been carried by friends or acquaintances, and their distribution across the range of Paul’s congregations suggests a steady stream of bearers. The letters served many social purposes and represent a range of concerns — letters of introduction would smooth friends’ travel, and build networks among the cities; letters in response to requests for advice on belief and practice — sometimes exasperated letters reining in wandering souls — would instruct the nascent communities, and shape the formation of churches for centuries; letters of gratitude for support during his imprisonments would encourage followers in the face of opposition; and there is one letter recommending its recipient free a free a man named Onesimus, who is thought to have been an escaped slave Paul met in Ephesus. He had probably come to seek refuge in the sanctuary of Artemis, and Paul sent him back to his owner — a fellow believer — with the letter encouraging his emancipation.

Acts also repeats stories of miracles Paul performed while in Ephesus. In this, too, there is a connection to the city itself. Ephesus had a reputation for magic. Paul’s miracles were seen as a sign of the strength and truth of his Lord, and inspired Ephesians to burn their books of magic. But the success of Paul’s mission was a threat to the city coffers. Acts notes that the books burned were worth 50,000 pieces of silver. And it also details a confrontation with the Ephesians who made their living from the tourists and pilgrims who came to the Temple of Artemis. While these stories provide vivid accounts of daily life in a city like Ephesus, it is likely that they exaggerate the threat Paul represented to the city’s economic well-being.

When the time came to depart, Paul headed north and west to his congregations in Macedonia, then south to Corinth once again.