From James C. Wright, Jr. Published in Christianity Today| Feb. 4, 1983

In a few days we will celebrate the birthday of our sixteenth President, Abraham Lincoln. There is so much inspirational quality in his life for all people, and especially today, that it should be profitable to spend a few minutes meditating upon it.

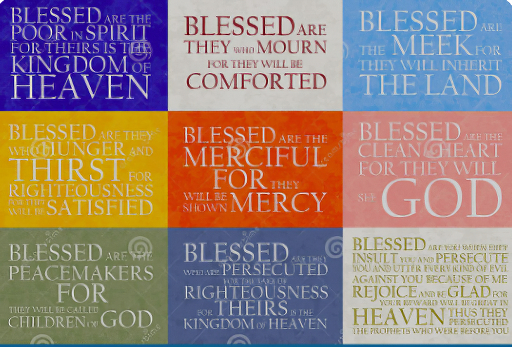

No other person in American history is known and quoted so widely. “What is it,” I have asked myself, “that makes Lincoln stand apart from all the rest?” The more we grope for the things that raised Lincoln to his distinctive pedestal of greatness, the more we are forced to conclude that they lay in the realm of the spirit. The attributes that were distinctively Lincoln’s were remarkably those set forth by Christ in the Beatitudes.

Lincoln was poor in the sense that Christ was poor. True, he had few financial resources. But more to the point, he had a basic spirit of humanity that is rare on the political scene. “Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

Lincoln was dogged by defeat, hounded by failure, and stalked by tragedy. From the loss of his mother, at the age of nine, grief followed his footsteps like an unshakeable shadow. The youthful love he shared with Ann Rutledge ended in heartache at her death. He knew unspeakable anguish at the death of his son Eddie at the age of four, and later, as President, the death of his beloved son Willie. But “Blessed,” said Christ, “are they that mourn.”

There can be no doubt as to Lincoln’s personal feelings about slavery. The spectacle of one human being owned as property by another did violence to his sense of right and wrong. On a trip to New Orleans as a young man he saw for the first time the true horrors of slavery. His conscience rebelled against the inhumanity of human creatures in chains, whipped and scourged. Then and there he swore an oath against the cruel and heartless institution, for it was wrong and reeked of evil. “Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness.”

Above his distaste for slavery, his greater passion was to save the nation. With the vision of the pure hearted, he knew the Union must endure. Still, he was a peaceful man, not a warmonger. He believed the North was as much responsible that slavery existed as was the South, and that both should bear equally the burdens of its elimination. Fanatic abolitionists railed against him and called him an appeaser and a compromiser.

Finally, as President, he proposed that the slaveholders would be recompensed by the government, paid $400 for each slave who was freed. He called representatives of the states to the White House and urged this settlement. They rejected the entire plan. Lincoln the peacemaker had failed, but, “Blessed are the peacemakers,” said Christ, “for they shall be called the children of God.”

Left no alternative, the President proceeded to gird the Union for war. He proclaimed the emancipation of the slaves, armed the Negroes, and devoted his singular energies to the distasteful business of destroying the enemy. Gloom hung heavy in the North and in the White House. Lincoln’s generals failed him, his cabinet snubbed him, the public reviled him.

The abuse he suffered would have made any ordinary man strike back in wounded pride. When Salmon Chase humiliated him and plotted against him, Lincoln praised Chase and made him chief justice of the Supreme Court. After Edwin Stanton had scorned him as an “imbecile,” Lincoln made him his secretary of war. “Blessed are the meek,” said Christ, “for they shall inherit the earth.”

When the war was finally over and Lee met Grant at Appomattox Court House, there were no humiliating ceremonies of capitulation. There was to be no vengeance such as that demanded by the Northern radicals who for four years had been insisting that Lee and others be hanged for treason. The terms of the surrender were remarkably generous and gentle. Why? Because Abraham Lincoln, just hours before his death, had personally dictated the terms. “Blessed are the merciful,” said Christ.

In the end, Lincoln had done what he had set out to do. Over the most difficult obstacle course to confront a career, he had fulfilled his mission. As he lay dying in the little rooming house across from Ford’s Theater, it remained for Edwin Stanton, his former detractor, to speak the fitting tribute: “There lies the most perfect ruler of men the world has ever seen … [and] now he belongs to the ages.”

Lincoln does belong to the ages because the virtues upon which his life were founded are timeless. They have been the message of God to mankind since the dawn of history. Jesus not only taught these principles of life, but he demonstrated them in every word spoken and in every act performed.

These are the qualities that make a people great, and the neglect of these is the source of evil in the world. My prayer to God is that men and women at all levels of society and in every nation will find in Christ the strength and the courage to demonstrate these virtues in the conduct of the affairs of individuals and of nations.