St. Peter's Episcopal Church, Port Royal, VA

We are a small Episcopal Church on the banks of the Rappahannock in Port Royal, Virginia. We acknowledge that we gather on the traditional land of the first people of Port Royal, the Nandtaughtacund, and we respect and honor with gratitude the land itself, the legacy of the ancestors, and the life of the Rappahannock Tribe. Our mission statement is to do God’s Will in all that we do.

Sept 21, 2025, Pentecost 15 & Season of Creation 3

Pentecost 15 – The Season of Creation 3

Pentecost 15 – The Season of Creation 3

Lectionary Pentecost 15, Year C

Commentary Pentecost 15, Year C, September 21, 2025

Visual Lectionary Vanderbilt, Fifteenth Sunday after Pentecost, Sept. 21, 2025

Podcast on the Gospel – “The Unjust Steward”

The Season of Creation, Sept 1 – Oct. 4, 2025

An Outline for the Season of Creation – Peace with Creation, Part 3

This week – Ecological Conversion

Ecological Conversion: A guide to individual action

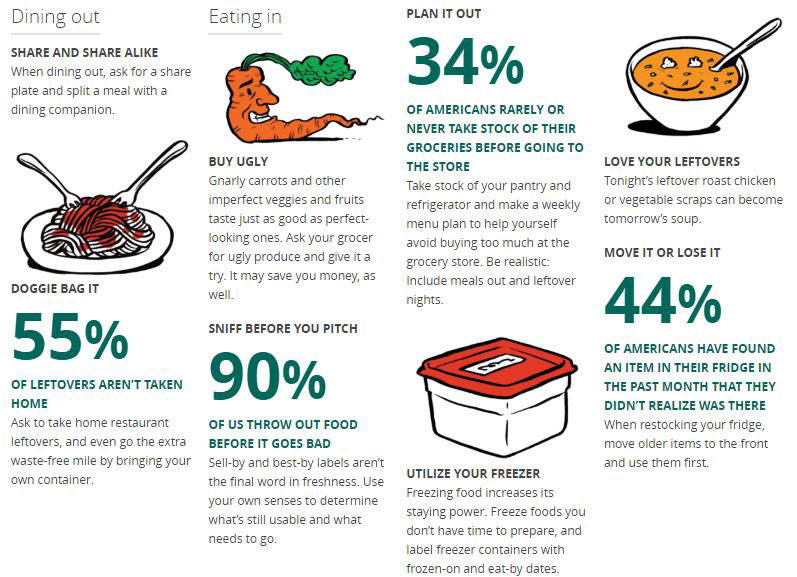

Food Waste

From a new book – The Relationship between Food and Climate Change

How to turn the tables on food waste – from TED

Get the Details on Recycling

A Spiritual look at Climate Change

Remembering…

Poem “Wild Geese” – Mary Oliver

Praying with Creation – Giant Goldenrod

Matthew, Sept 22.

Lancelot Andrewes (1555-1626), Sept 26.

I. Theme – Using our resources—financial and otherwise—for justice and compassion

“Parable of the Shrewd Manager – Coptic (Egypt) ”

The lectionary readings are here or individually:

First Reading – Amos 8:4-7

Psalm – Psalm 113

Epistle – 1 Timothy 2:1-7

Gospel – Luke 16:1-13

Today’s readings call us to use our resources—financial and otherwise—for justice and compassion. They reflect on the social consequences of turning away from God and the possibility that prayer and God-centered values can be a source of health in our personal and corporate lives. A transformed mind may lead over the long haul to transformed social systems.

Amos condemns the callousness of those who observe rituals but set their hearts on greed and dishonesty. Paul urges prayers for peace, godliness and dignity, made possible by Christ, who bridges the gap between God and humanity. In Jesus’ story, the master appreciates the shrewdness of an unfaithful servant.

The parable from the Gospel also presents most congregations with serious challenges in terms of values, ethics, and priorities. You cannot serve God and money. One has to come first; one has to be the lens through which you make your personal and corporate decisions. Studies suggest that great wealth does not lead to greater happiness. In light of the Hebraic prophetic scriptures, wealth without justice and compassion leads to personal and corporate destruction. Wealth without consideration of God’s Shalom and purposes beyond our self-interest leads to poverty and pain.

Click here to view in a new window.

“Parable of the Unjust Steward -Marinus van Reymerswaele” (1540, Dutch)

This 5 minute podcast was constructed by NotebookLM from the following sources provided to it:

1. The Gospel story

2. 2013 St. Peter’s Sermon

3. Working Preacher, 2025 – John Carroll

3. Working Preacher, 2013 – Lois Malcolm

3. Working Preacher, 2019 – Mitzi Smith

4. Poems on the Unjust Steward

5. Art on the Unjust Steward

An alternate to this podcast is to read the Briefing Document. The Briefing Document is here

The fight against climate change can feel overwhelming, but individuals hold significant power to drive meaningful change through conscious and collective action. By making informed choices in our daily lives, we can collectively reduce our carbon footprint and contribute to a more sustainable future. This guide outlines key areas where personal efforts can make a substantial impact.

High-Impact Lifestyle Changes

Recent studies have highlighted several high-impact actions that can drastically reduce an individual’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. While not feasible for everyone, understanding these can provide a framework for prioritizing efforts.

Everyday Actions for a Greener Lifestyle

Beyond these major shifts, a multitude of daily habits can collectively contribute to a more sustainable way of life.

In the Home:

On Your Plate:

As a Consumer:

The Power of Collective Action and Advocacy

While individual actions are crucial, they are most powerful when they contribute to a larger movement.

By embracing a combination of these strategies, individuals can move beyond feeling helpless and become active participants in the global effort to combat climate change. Every conscious choice, no matter how small it may seem, contributes to a larger wave of change that is essential for protecting our planet for future generations.

1. Food Waste

The local food banks and other distributors have worked out agreements with restaurants to help eliminate waste by taking foods they cannot sell due to sell by dates and redistributing the foods. Globally, the issue of waste is a large one.

World Wildlife Federation has covered the topic in its Fall, 2018 magazine.

“Today, 7.3 billion people consume 1.6 times what the earth’s natural resources can supply. By 2050, the world’s population will reach 9 billion and the demand for food will double.

“So how do we produce more food for more people without expanding the land and water already in use? We can’t double the amount of food. Fortunately we don’t have to—we have to double the amount of food available instead. In short, we must freeze the footprint of food.

“In the near-term, food production is sufficient to provide for all, but it doesn’t reach everyone who needs it. In fact, one-third of the world’s food—1.3 billion tons—is lost or wasted at a cost of $750 billion annually. When we throw away food, we waste the wealth of resources and labor that was used to get it to our plates. In effect, lost and wasted food is behind more than a quarter of all deforestation and nearly a quarter of global water consumption. It generates as much as 10% of all greenhouse-gas emissions. As it rots, it pollutes water and soil and releases huge amounts of methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gases.

“Another negative aspect of food waste is its connection to species loss. Consider this: Food production is the primary threat to biodiversity worldwide, expected to drive an astonishing 70% of projected terrestrial biodiversity loss by 2050. That loss is happening in the Amazon, where rain forests are still being cleared to create new pasture for cattle grazing, as well as in sub-Saharan Africa, where agriculture is expanding rapidly. But it’s also happening close to home.

“These wasted calories are enough to feed three billion people—10 times the population of the United States, more than twice that of China, and more than three times the total number of malnourished globally. Wasted food may represent as much as 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and is a main contributor to deforestation and the depletion of global water sources.

“By improving efficiency and productivity while reducing waste and shifting consumption patterns, we can produce enough food for everyone by 2050 on roughly the same amount of land we use now. Feeding all sustainably and protecting our natural resources.”

South Korea has a system that keeps about 90 percent of discarded food out of landfills and incinerators, has been studied by governments around the world. But the country’s mountainous terrain limits how many landfills can be built, and how far from residential areas they can be built.

Since 2005, it’s been illegal to send food waste to landfills. Local governments have built hundreds of facilities for processing it. Consumers, restaurant owners, truck drivers and others are part of the network that gets it collected and turned into something useful.

In the case of a restaurant when it gets to a plant. Debris — bones, seeds, shells — is picked out by hand though most facilities are automated. A conveyor belt carries the waste into a grinder, which reduces it to small pieces. Anything that isn’t easily shredded, like plastic bags, is filtered out and incinerated.

Then the waste is baked and dehydrated. The moisture goes into pipes leading to a water treatment plant, where some of it is used to produce biogas. The rest is purified and discharged into a nearby stream.

What’s left of the waste at the processing plant, four hours after Mr. Park’s team dropped it off, is ground into the final product: a dry, brown powder that smells like dirt. It’s a feed supplement for chickens and ducks, rich in protein and fiber, said Sim Yoon-sik, the facility’s manager, and given away to any farm that wants it.

For consumers, at apartment complexes around the country, residents are issued cards to scan every time they drop food waste into a designated bin. The bin weighs what they’ve dropped in; at the end of the month they get a bill.

A focus in the Season of Creation is considering how we interact with the natural world and where we need to change our relationship to it. This book covers both of these.

We are looking at notes from the book We Are Eating the Earth The Race to Fix Our Food System and Save Our Climate by Michael Grunwald, published 2025. Grunwald is a journalist who has has worked at Politico Magazine as well as newspapers the Boston Globe and Washington Post.

Food is a necessity but we are challenged by an expanding population. We can cultivate more food on farms but his causes increases in our carbons emissions. We can clear more land to increase lands under cultivation but this affects deforestation. Trees are a carbon sink storing up food rather than releasing food into the atmostpher. Moreover as we expand our cultivated land, food production generated a third of our carbon emissions affecting climate change.

Grunwald says “We are eating the earth”.We have to fix our food systems to ultimately benefit our climate.

The core challenge involves closing three “gaps” by 2050:

Achieving these goals requires a multi-faceted approach, involving significant changes in both food consumption and production patterns.

Here are the most impactful and feasible strategies identified:

Transcript

Inevitably, we’re sitting there at the end of the meal, they’re pushing food around their plate, they don’t want to eat, and they’re looking at me with some awkward excuse. And I say, like, we can’t eat our way out of this. This is a systems problem. And it’s just way too big. How big?

It’s the size of the entire United States. It uses three times as much water as the whole country. And it grows food all year long, and when harvested, produces enough to fill 100 tractor trailers every minute, all year long. Those trucks then drive, fly and float all over the world. Except instead of going somewhere to be eaten, they go straight to landfill, where the food rots and produces nothing. A powerful greenhouse gas. Seems crazy, right? But that’s effectively what we’re doing, from science experiments in the back of our refrigerators to truckloads of products that are too close to some arbitrary expiration date

Globally, 1 billion meals are wasted. Go any in every single day. That’s more than a meal per person for everyone on this planet who faces hunger. Not to mention it’s worth $1 trillion. And this whole ridiculous exercise has five times the greenhouse gas footprint of the entire aviation industry.

Can I Recycle This? A Guide to Better Recycling and How to Reduce Single-Use Plastics by Jennie Romer is a comprehensive guide to understanding the complexities of recycling and reducing single-use plastics in the U.S. Romer, an attorney and sustainability consultant, is a leading expert on single-use plastic reduction and recycling

The book is divided into two parts. The first part is an explanation of recycling and the process.

It explains the seven Resin Identification Codes (1-7), often enclosed in chasing arrows. Many consumers mistakenly believe the chasing arrows mean an item is automatically recyclable, but the number only identifies the type of plastic resin. Only PET #1 and HDPE #2 bottles and jugs consistently meet the FTC’s definition of recyclable.

While many remember the “3R’s” “recycle, reduction and reuse”, the latter two are far more important. Recycling itself consumes significant resources (fuel, water, greenhouse gas emissions), making reuse and reduction better for the environment,

The second part, the longest section is a look-up designed to be a handy reference. Some key points:

Most Recyclable (Green): Metal (especially aluminum cans), paper products with long fibers (cardboard, paper bags), bottles and jugs. Steel cans and clean cardboard boxes are valuable.

◦ Recyclable, but have issues (Yellow): Glass bottles (issues with mixed colors, transportation costs, regional variations). thermoforms (less valuable than bottles, not accepted everywhere).

◦ Not Recyclable (Red):

▪ Tanglers: Plastic films/carryout bags, clothing hangers, clothing/fabric, garden hoses, extension cords, Christmas lights.

▪ Smalls: Plastic straws, colorful plastic party cups, orphaned bottle caps, plastic forks, coffee pods, condiment cups.

▪ Mixed Materials/Multilayer Packaging: Juice pouches, cocktail peanut cans, chip bags, candy wrappers, baby food pouches, toothpaste tubes, cell phones, laptops, eyeglasses, blister packs.

▪ EPS/Foam: Foam coffee cups, foam egg cartons.

▪ Other Not Recyclable: Batteries (fire hazard), light bulbs (mercury/fragility), dirty/waxed paper, face masks.

The book is not just an encyclopedia of what can and can’t be recycled, but promotes understanding of the recycle process which most of us are involved with on a daily basis. Thus, the book is highly recommended.

The ultimate test of a moral society is the kind of world that it leaves to its children.” –Dietrich Bonhoeffer

1. Creation is a reflection of the glory of God to be good stewards of God’s creation, which includes all of us who live within it

2. Climate change is a spiritual challenge. Handling climate change is part of how we live our faith.

3. We have a responsibility to care for the least of us. The poorest amongst us bear the greatest burden and risk of climate change.

4. We are called to respond to what we see around us. We are moral messengers for the common good, translate compassion into action.

This week on Sept 22 we reach the autumn equinox. What better way to celebrate this transition than with a poem by Mary Oliver!

Canada Geese migrate south in winter and north in summer. We may assume the poem may set in the fall when they are flying south for food, but Oliver never tells us where is home.

Home may not just be a destination but our efforts to connect to one another. We may fly alone but like geese we may be call out to others so we may connect in the “family of things.” We have much in common – “Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine…” Communication can be a part of the healing which creates bonds to one another.

However, we shouldn’t dwell in despair since Oliver sees the world going on. Yes it can be “harsh” but “exciting “, open to our “imagination. We just have to be a part of it, traveling like the seasons. Oliver’s imagery is rich – rain going across America and the geese flying.

Oliver’s imagery is rich as the world she describes. She won many awards for her writings among these, the Pulitzer prize and the National Book award.

From “Praying with Creation: Daily Devotions for the Season of Creation from the Province One EcoRegion”

“Giant goldenrod is a perennial that can grow almost 6 feet tall! It has a central stem which then breaks off into branches, each bearing its own golden flowers, sometimes called sprays.

“These flowers bloom in late summer into early fall—August, September, and October being typical blooming months. In addition to its beauty, goldenrod is highly beneficial to the environment. Because of the large amount of nectar and pollen it produces, “it supports bees, wasps, butterflies, moths, and beetles…. it produces high-quality pollen, rich in fats and minerals, making it helpful for migratory insects such as the monarch butterfly” (Denise D’Aurora, Master Gardener, Crawford County, Penn State Extension website extension.psu.edu).

“Another benefit of goldenrod is that it can be used to “prevent soil erosion, stabilizing slopes and controlling erosion along stream banks… well-adapted to …conditions…. ranging from dry sand soils to moist clayey ones” (content.gardenforwildlife.com).

“While shining in her beauty, goldenrod is also laboring on behalf of creation to support an ecosystem where life can thrive and blossom. The botanical name of Goldenrod is solidago. Solidago is Latin for solidus, meaning “to make whole.” This reference is to “the plant’s healing and medicinal properties. Goldenrod has been used to heal wounds of the skin, and to treat inflammation of the mouth and throat as well as tuberculosis, diabetes, and arthritis”

Sept. 22 is the day we celebrate the life of the author of the Gospel of Matthew, both Apostle and evangelist due to the Book he wrote.

The meeting between Jesus and Matthew is told in Matthew 9:9–13: 9 As Jesus passed on from there, he saw a man called Matthew sitting at the tax booth, and he said to him, “Follow me.” And he rose and followed him.

10 And as Jesus reclined at table in the house, behold, many tax collectors and sinners came and were reclining with Jesus and his disciples. 11 And when the Pharisees saw this, they said to his disciples, “Why does your teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners?” 12 But when he heard it, he said, “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick. 13 Go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy, and not sacrifice.’ For I came not to call the righteous, but sinners.”

Matthew was one of the 12 apostles that were with Jesus Christ throughout His public ministry on earth. The consensus among scholars is that this book in the Bible was written in the mid-70’s, 40 years after the resurrection. It was the second Gospel written after Mark, 10 years earlier.

Matthew was a Jewish tax collector who left his profession to follow Jesus. As an apostle of the Lord, he dedicated his life to spreading the Gospel and leading the early church. Matthew gives a personal witness account of many miracles that Jesus performed prior to being crucified on a Roman cross.

He wrote after the destruction of the temple by the Romans and massacre of the Jewish priests. Many thought they were in the end days. He was a Greek speaker who also knew Aramaic and Hebrew. He drew on Mark and a collection of the sayings of the Lord (Q), as well as on other available traditions, oral and written. He was probably a Jewish Christian and we think the book was written in Antioch in Syria where a community had developed.

The purpose of this book is to prove to readers that Jesus is the true Messiah that was prophesized in the Old Testament of the Bible. The Kingdom begins with us . The author of the Gospel of Matthew, more than the other synoptic writers, explicitly cites Old Testament messianic writings. With 28 chapters, it is the longest Gospel of the four.

It begins by accounting the genealogy of Jesus, showing him to be the true heir to David’s throne. The genealogy documents Christ’s credentials as Israel’s king. Then the narrative continues to revolve around this theme with his birth, baptism, and public ministry.

The Sermon on the Mount highlights Jesus’ moral teachings and the miracles reveal his authority and true identity. Matthew also emphasizes Christ’s abiding presence with humankind

The Gospel organizes the teachings of Jesus into five major discourses: the Sermon on the Mount (chapters 5-7), the Commissioning of the 12 Apostles (chapter 10), the Parables of the Kingdom (chapter 13), the Discourse on the Church (chapter 18), and the Olivet Discourse (chapters 23-25). The emphasis corresponds to the 5 great books of the Old Testament, the Pentateuch .

He preached the Gospel in Judea before embarking on missions to other lands, with Ethiopia often cited as one of his destinations. One notable tradition associated with Matthew involves his encounter with King Hirtacus in Ethiopia. Matthew’s steadfast devotion to his faith led him to confront the king for lusting after Ephigenia, a nun consecrated to God. Matthew’s rebuke, delivered at a Mass, ultimately led to his martyrdom, solidifying his commitment to his faith

Lancelot Andrewes’ life (1555-1626) encompassed the reigns of Elizabeth (1558-1603) and James I (1603-1625). He was closely associated with both of them. We celebrate his day on his death Sept 26, 1626.

Andrewes was the foremost theologian of his day and one of the most pious. He will be forever linked to the creation of the King James Bible being on the committee that created the book. He served not only as the leader of the First Westminster Company of Translators, which translated Genesis – 2 Kings, but also as general editor of the whole project. His contemporaries include everyone from Shakespeare, Sir Walter Raleigh, Captain John Smith who ventured to Virginia and scientist Galileo.

A concise description of him can be found in God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible, noting his intellectual abilities as well as a man close to the ordinary Englishman. “This was the man who was acknowledged as the greatest preacher of the age, who tended in great detail to the school-children in his care, who, endlessly busy as he was, would nevertheless wait in the transepts of Old St Paul’s for any Londoner in need of solace or advice, who was the most brilliant man in the English Church, destined for all but the highest office. There were few Englishmen more powerful. Everybody reported on his serenity, the sense of grace that hovered around him. But alone every day he acknowledged little but his wickedness and his weakness. The man was a library, the repository of sixteen centuries of Christian culture, he could speak fifteen modern languages and six ancient, but the heart and bulk of his existence was his sense of himself as a worm. Against an all-knowing, all-powerful and irresistible God, all he saw was an ignorant, weak and irresolute self”

A man of intense piety who spent five hours every morning in prayer, Andrewes kept in that chapel a book of private devotions which, when published after his death, became a classic Anglican guide to prayer.